Category: Uncategorized

-

López Medrano (JPMorgan): “Hemos duplicado el equipo de banqueros y vamos a seguir contratando”El banco americano está inmerso en una importante estrategia de crecimiento entre grandes clientes y busca duplicar el negocio. Leer

-

Los Riberas se reparten 2.300 millones en dividendos con su hólding Acek

Los hermanos Riberas controlan, a través de Acek, los gigantes industriales Gestamp y Gonvarri y participan en Cie Automotive o Dominion. Leer

Los hermanos Riberas controlan, a través de Acek, los gigantes industriales Gestamp y Gonvarri y participan en Cie Automotive o Dominion. Leer -

Madrid y Barcelona: las subidas de la vivienda se extienden en sus áreas metropolitanas

En la mayoría de los municipios de la periferia de estas dos capitales los precios inmobiliarios aumentan más de un 10% en tercer trimestre, pero atraen a los compradores porque siguen siendo más económicos que en el centro. Leer

En la mayoría de los municipios de la periferia de estas dos capitales los precios inmobiliarios aumentan más de un 10% en tercer trimestre, pero atraen a los compradores porque siguen siendo más económicos que en el centro. Leer

Florian Wehde -

Una enfermedad que no afecta a la salud humana directa pero sí a la economía

Numerosas organizaciones científicas y sanitarias insisten en que la fiebre porcina africana no puede transmitirse a los humanos por contacto con cerdos o jabalíes o por el consumo de productos de estos animales. Pero las consecuencias económicas y de seguridad alimentaria pueden llegar a ser muy graves. Leer

Numerosas organizaciones científicas y sanitarias insisten en que la fiebre porcina africana no puede transmitirse a los humanos por contacto con cerdos o jabalíes o por el consumo de productos de estos animales. Pero las consecuencias económicas y de seguridad alimentaria pueden llegar a ser muy graves. Leer -

La Generalitat de Cataluña pide el despliegue de la UME ante el brote de peste porcina

Taiwán prohibió la importación de carne y productos porcinos procedentes de España tras la detección de varios casos de peste porcina africana (PPA) en jabalíes hallados muertos en la sierra de Collserola, cerca de Barcelona, el primer brote registrado en el país desde 1994. Leer -

Por qué preocupan los datos poco fiables de China

La creciente opacidad estadística y el control político en China generan dudas sobre sus cifras oficiales, e impiden conocer el alcance real de la desaceleración de la segunda economía mundial. Leer

La creciente opacidad estadística y el control político en China generan dudas sobre sus cifras oficiales, e impiden conocer el alcance real de la desaceleración de la segunda economía mundial. Leer -

Así gestiona su fortuna la familia March

Con un patrimonio de 5.100 millones, los March llevan generaciones afianzando su liderazgo en el sector privado con Banca March y Corporación Alba. Gestionan Torrenova, la segunda mayor Sicav en España. Leer

Con un patrimonio de 5.100 millones, los March llevan generaciones afianzando su liderazgo en el sector privado con Banca March y Corporación Alba. Gestionan Torrenova, la segunda mayor Sicav en España. Leer -

Physicality: the new age of UI

It’s an exciting time to be a designer on iOS. My professional universe is trembling and rumbling with a deep sense of mystery. There’s a lot of rumors and whispers of a huge redesign coming to the iPhone’s operating system — one that is set to be ‘the biggest in a long time’.

There’s only been one moment that was similar to this: the spring of 2013. On June 10th, Apple showed off what would be the greatest paradigm shift in user interface design ever: iOS 7. I remember exactly where I was and how I felt. It was a shock.

If there is indeed a big redesign happening this year, it’ll be consequential and impactful in many ways that will dwarf the iOS 7 overhaul for a multitude of reasons. The redesign is rumored to be comprehensive; a restyling of iOS, macOS, iPadOS, tvOS, watchOS and visionOS. In the intervening years between iOS 7’s announcement and today, iPhones have gone from simply a popular device to the single most important object in people’s lives. The design of iOS affected and inspired most things around, from the web to graphic design and any other computer interface.

That’s why I figured I’d take this moment of obscurity, this precious moment in time where its changes are still shrouded in fog to savor something: wholesale naivety of where things are going, so I can let my imagination run wild.

What would I do if I were Apple’s design team? What changes would I like to see, and what do I think is likely? Considering where technology is going, how do I think interface design should change to accommodate? Let’s take a look at what’s (or what could be) next.

Smart people study history to understand the future. If we were to categorize the epochs of iOS design, we could roughly separate them into the Shaded Age, the Adaptive Age, and the New Age.

The Shaded Age

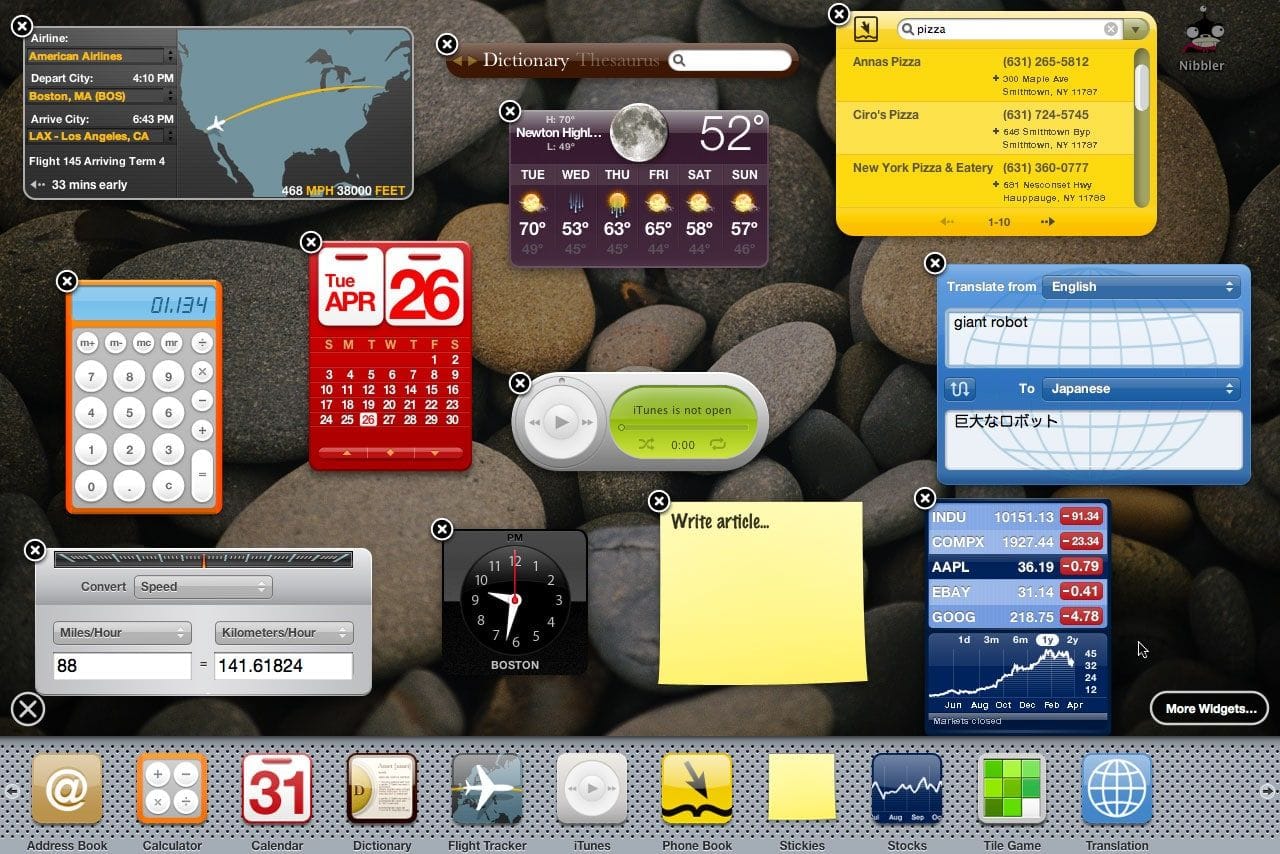

iOS started out as iPhone OS, an entirely new operating system that had very similar styling to the design language of the Mac OS X Tiger Dashboard feature:

via https://numericcitizen.me/what-widgets-on-macos-big-sur-should-have-been/

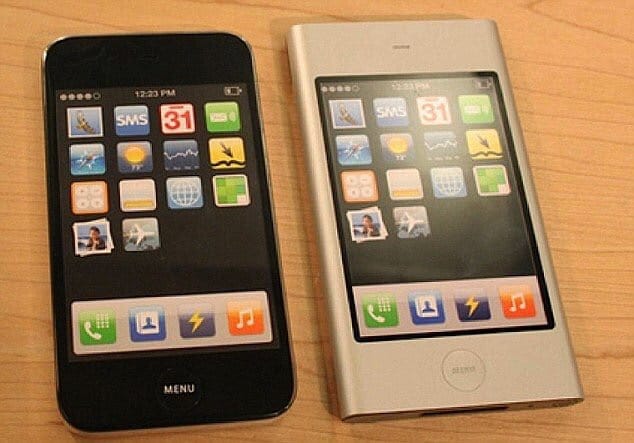

early iPhone prototypes with Dashboard widget icons for apps The icon layout on iPhone OS 1 was a clear skeuomorph.

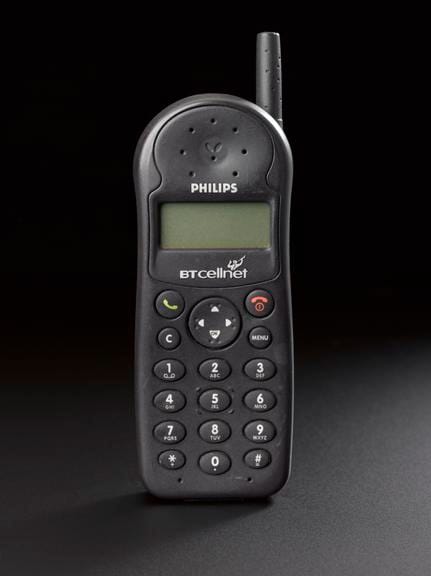

You might’ve heard that word being thrown around. It might surprise you that that doesn’t mean it has lots of visual effects like gradients, gloss and shadows. It actually means that to make it easier for users to transition from something they were used to — in this case, phones typically being slabs with a grid of buttons on them — to what things had become — phones were all-screen, so they could show any kind of button or interface imaginable.

At the time of iPhone 1’s launch, a cartoon of a ‘phone’ would still be drawn as the image on the left. A grid of buttons defined its interaction model and comfort zone.

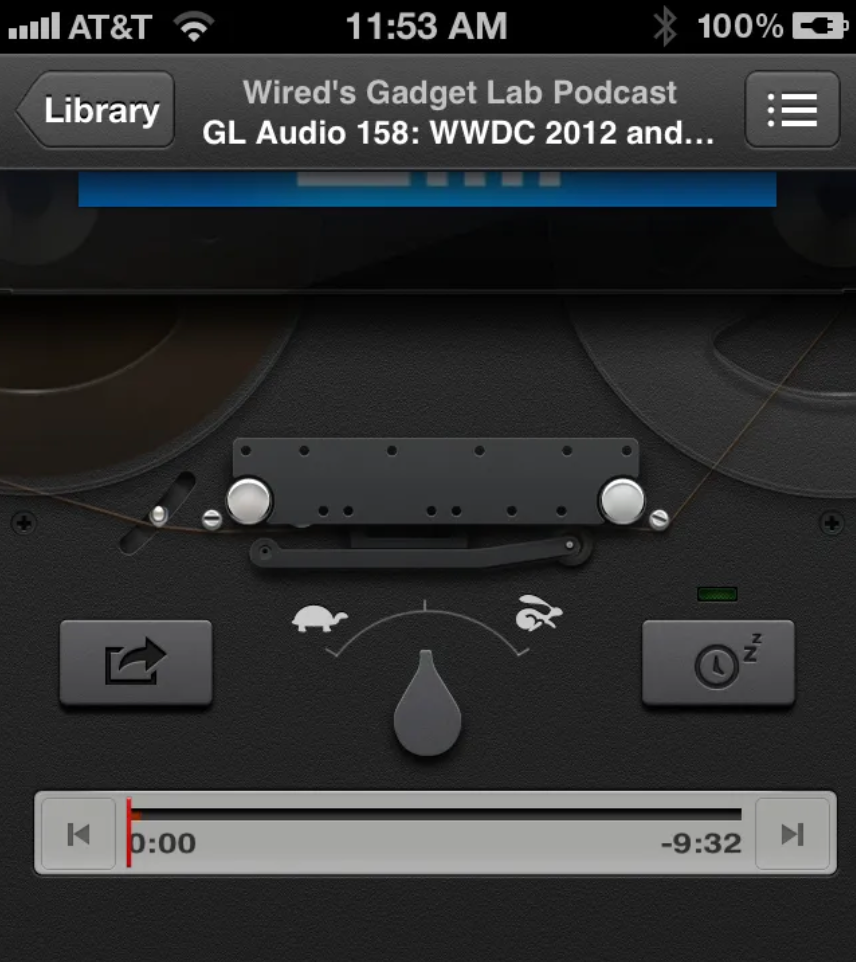

And yes, there was a whole lot of visual effects in user interfaces from iPhone OS 1 to iOS 6. In this age, we saw everything from detailed gradients and shadows in simple interface elements to realistically rendered reel-to-reel tape decks and microphones for audio apps.

The Facebook share sheet had a paperclip on it! The texture of road signs on iOS maps was composed of hundreds of tiny hexagons! Having actually worked on some of the more fun manifestations of it during my time working at Apple, I can tell you from experience that the work we did in this era was heavily grounded in creating familiarity through thoughtful, extensive visual effects. We spent a lot of time in Photoshop drawing realistically shaded buttons, virtual wood, leather and more materials.

That became known as ‘skeuomorphic design’, which I find a bit of a misnomer, but the general idea stands.

Of course, the metal of the microphone was not, in fact, metal — it didn’t reflect anything like metal objects do. It never behaved like the object it mimicked. It was just an effect; a purely visual lacquer to help users understand the Voice Memos app worked like a microphone. The entire interface worked like this to be as approachable as possible.

Notably, this philosophy extended even to the smallest elements of the UI: buttons were styled to visually resemble a button by being convex and raised or recessed; disabled items often had reduced treatments to make them look less interactive. All of this was made to work with lots of static bitmap images.

The first signs of something more dynamic did begin to show: on iPad, some metal sliders’ sheen could respond to the device orientation. Deleting a note or email did not simply make it vanish off-screen, but pulled it into a recycling bin icon that went as far as to open its lid and close it as the document got sucked in.

If it had not been for Benjamin Mayo publishing this video, no trace of this was ever even findable online. Our brand new, rich, retina-density (2×) screens were about to see a radical transformation in the way apps and information were presented, however…

The Flat Age

iOS 7 introduced an entirely new design language for iOS. Much was written on it at the time, and as with any dramatic change the emotions in the community ran quite high. I’ll leave my own opinions out of it (mostly), but whichever way you feel about it, you can’t deny it was a fundamental rethinking of visual treatment of iOS.

iOS 7 largely did away with visual effects for suggesting interactivity. It went back to quite possibly the most primitive method of suggesting interactivity on a computer: some ‘buttons’ were nothing more than blue text on a white background.

The styling of this age is often referred to as ‘flat design’. You can see why it is called that: even the buttons in the calculator app visually indicate no level of protuberance:

The Home Screen, once a clear reference to the buttons on phones of yesteryear, was now much more flat-looking — one part owing to simpler visual treatment but also a distinct lack of usage of shadows.

But why did shadows have to go? They had an important function in defining depth in the interface, after all. Looking at the screenshot above actually does it no justice: the new iOS 7 home screen was anything but flat. The reason was that the shadows were static.

iOS 7 embraced a notion of distinct visual layers and using adaptive or dynamic effects to distinguish depth and separation. Why render flat highlights and shadows that are unresponsive to the actual environment of the user when you can separate the icons by rendering them on a separate plane from the background? Parallax made the icons ‘float’ distinctly above the wallpaper. The notification center sheet could simply be a frosted pane above the content which blurred its background for context.

Jony Ive proudly spoke at the iOS 7 introduction, on how ‘the simple act of setting a different wallpaper’ affected the appearance of many things. This was a very new thing.

Also a new thing in the interface was that the UI chrome was able to have the same dynamics: things like the header and keyboard could show some of the content they obscured shining through as if fashioned out of frosted glass.

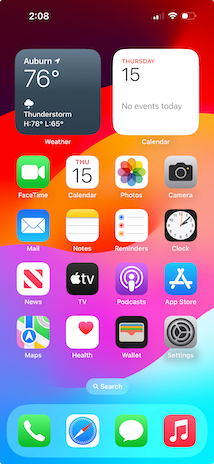

While it was arguably an overcorrection in some places, iOS 7’s radical changes were here to stay — with some of its dynamic ‘effects’ getting greatly reduced (parallax is now barely noticeable). Over time, its UI regained a lot more static effects.

Type and icons grew thicker, shadows came back, and colors became a lot less neon.

One of the major changes over time was that iOS got rounder; in step with the hardware it came on, with newly curved screen corners and ever-rounder iPhones, the user interface matched it in lock-step. It even did this dynamically based on what device it was running on.

More interface elements started to blend with content through different types of blur like the new progressive blur, and button shapes were slowly starting to make a comeback. It settled into a stable state — but it was also somewhat stagnant. For bigger changes, there would have to be a rethink.

What would come next couldn’t simply be a static bitmap again: it would have to continue the trend of increasingly adaptive interfaces.

The Age of Physicality

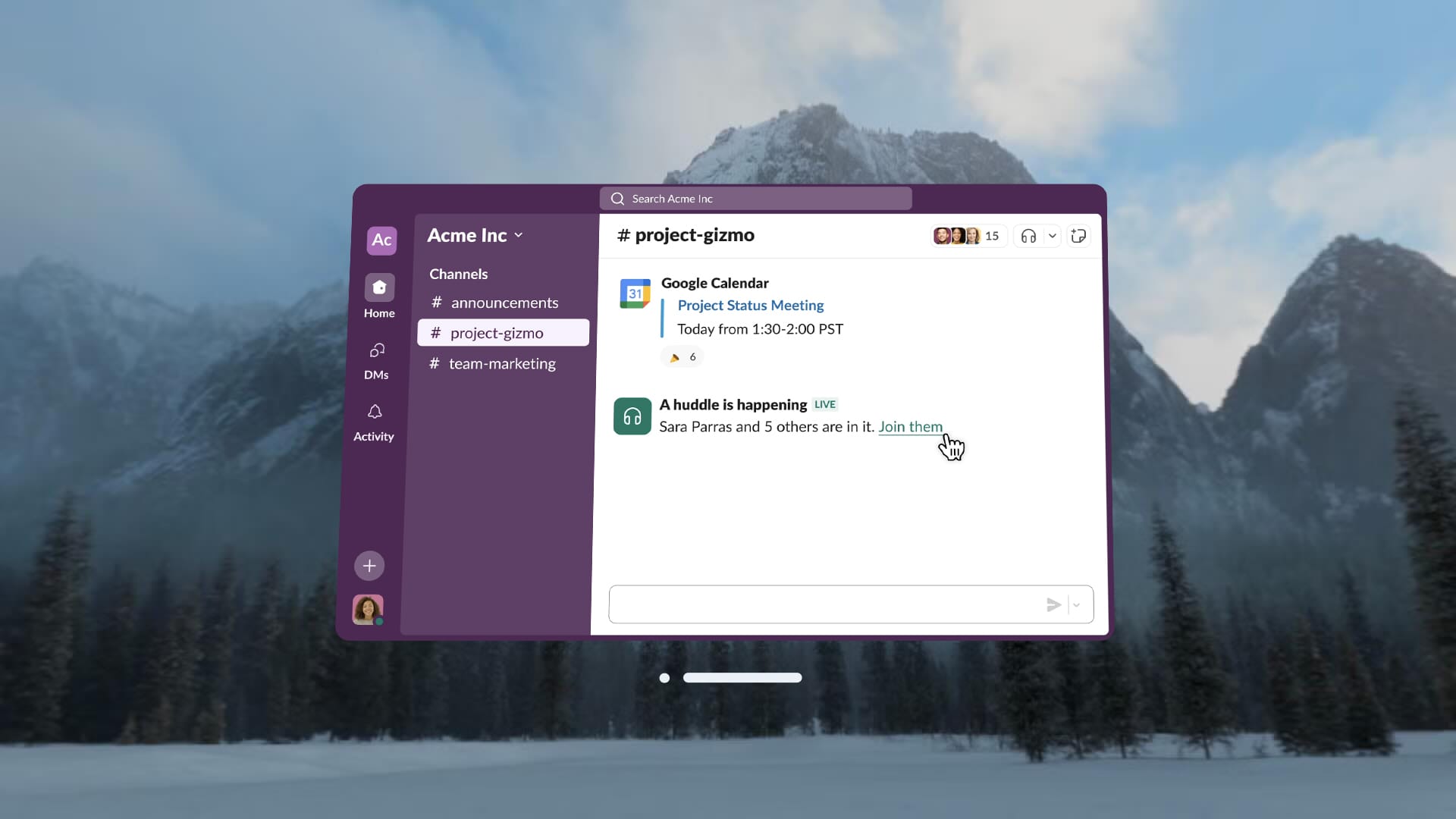

When Apple’s designers imagined the interface of VisionOS, they had a mandate to essentially start from scratch. What does an ‘app’ look like in an augmented reality?

What appears to be a key foundational tenet of the VisionOS design language is how elements are always composed of ‘real’ materials. No flat panels of color and shapes exist as part of the interface.

This even applies to app icons: while they do have gradients of color, they occupy discrete layers of their own, with a clear intention from their introduction video of feeling like actual ‘materials’:

Alan Dye, upon introduction of the VisionOS interface, stated that every element was crafted to have a sense of physicality: they have dimension, respond dynamically to light, and cast shadows.

This is essential in Vision Pro because the interface of apps should feel like it can naturally occupy the world around you and have as much richness and texture as any of the objects that inhabit that space. Comparing to the interfaces we are familiar with, that paradigm shift is profound, and it makes older, non physicality-infused interfaces feel archaic.

If I were to position a regular interface in the Vision Pro context, the result looks almost comically bad:

I find it likely, then, that there will be more than a mere static visual style from visionOS brought to iPhone, iPad and Mac (and potential new platforms) — it seems likely that a set of new fundamental principles will underpin all of Apple’s styling across products and expressions of its brand.

It would have to be more subtle than on Vision Pro – after all, interfaces do not have to fit in with the ‘real world’ quite as much – but dynamic effects and behavior essentially make the interface come to life.

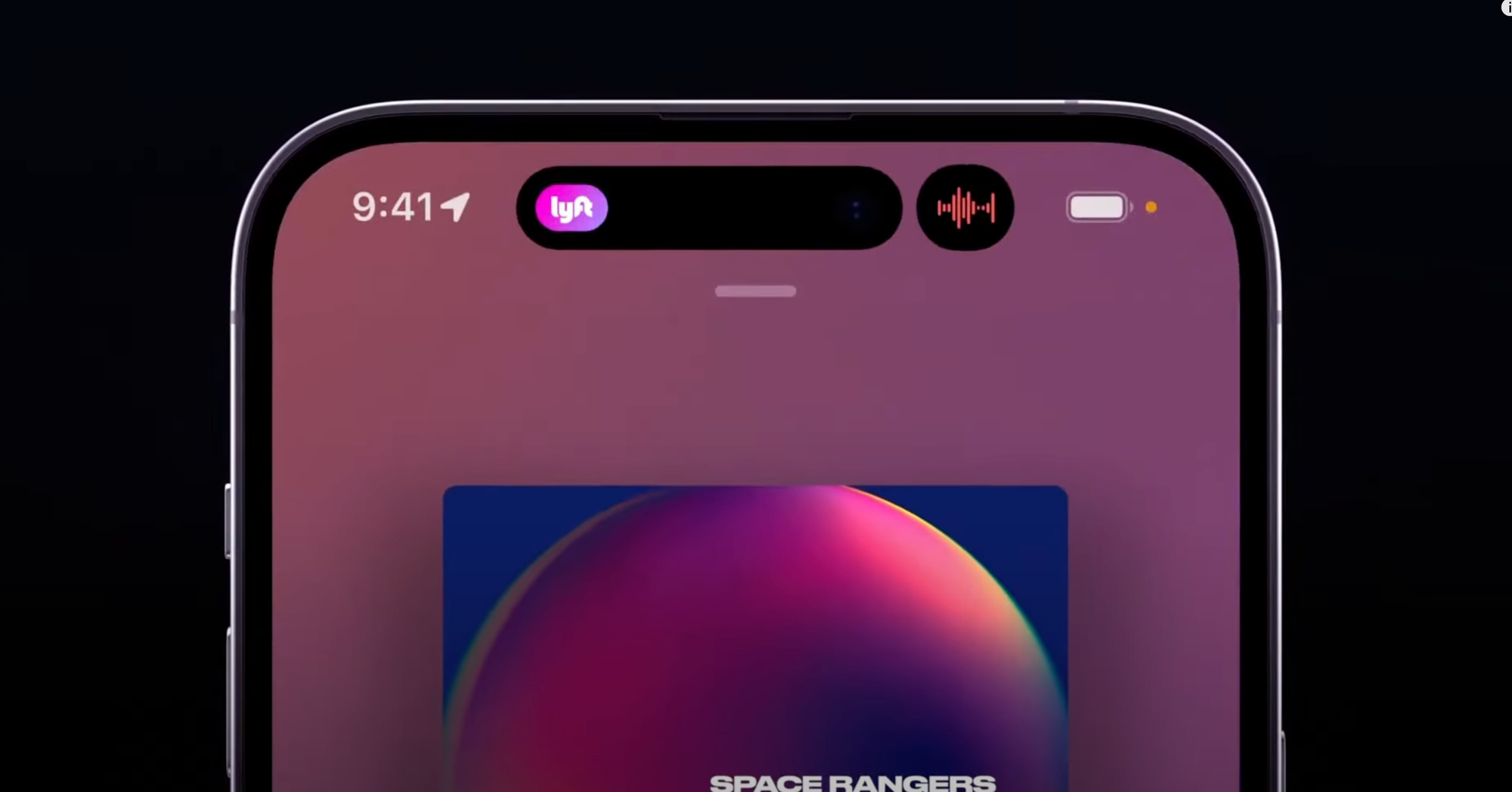

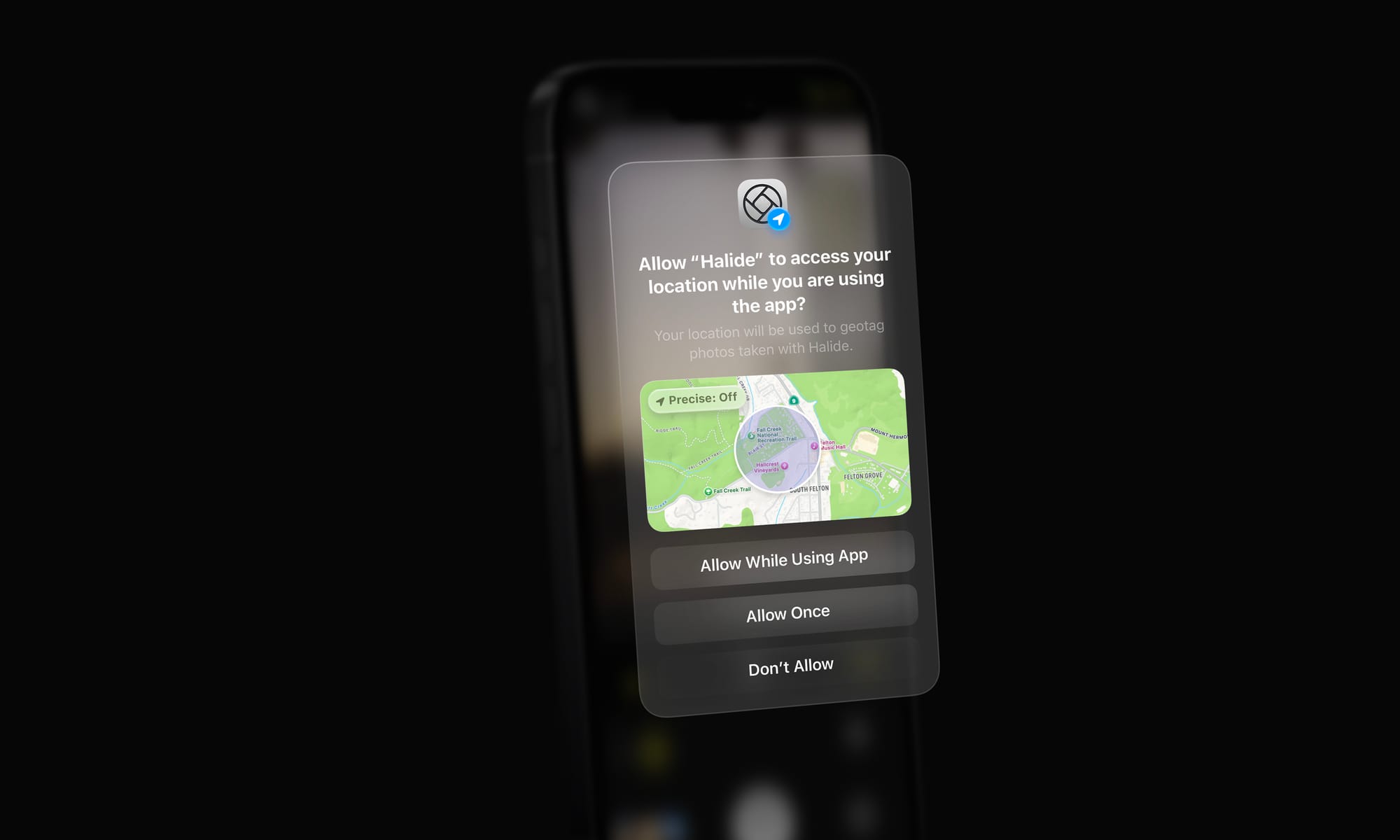

Sound familiar? Existing aspects of the iPhone user interface already do this:

0:00/0:17

Apple’s new additions to the iOS interface of the last years stand out as being materially different compared the rest of the interface.

They are completely dynamic: inhabiting characteristics that are akin to actual materials and objects. We’ve come back, in a sense, to skeuomorphic interfaces — but this time not with a lacquer resembling a material. Instead, the interface is clear, graphic and behaves like things we know from the real world, or might exist in the world. This is what the new skeuomorphism is. It, too, is physicality.

The Dynamic Island is a stark, graphic interface that behaves like an interactive, viscous liquid:

You can see it exhibiting qualities unique to its liquid material, like surface tension, as parts of it come into contact and meld together.

When it gains speed, it has momentum, much like the scrolling lists of the very first iteration of iPhoneOS, but now it reads more realistic to us as it also has directional motion blur or a plane of focus as items move on their plane:

Similarly, the new Siri animation behaves a bit more like a physically embodied glow – like a fiery gas or mist that is attracted to the edges of the device and is emitted by the user’s button press or voice.

What could be the next step?

My take on the New Age: Living Glass

I’d like to imagine what could come next. Both by rendering some UI design of my own, and by thinking out what the philosophy of the New Age could be.

A logical next step could be extending physicality to the entirety of the interface. We do not have to go overboard in such treatments, but we can now have the interface inhabit a sense of tactile realism.

Philosophically, if I was Apple, I’d describe this as finally having an interface that matches the beautiful material properties of its devices. All the surfaces of your devices have glass screens. This brings an interface of a matching material, giving the user a feeling of the glass itself coming alive.

VisionOS details from the excellent Wallpaper interview with Apple’s design team.

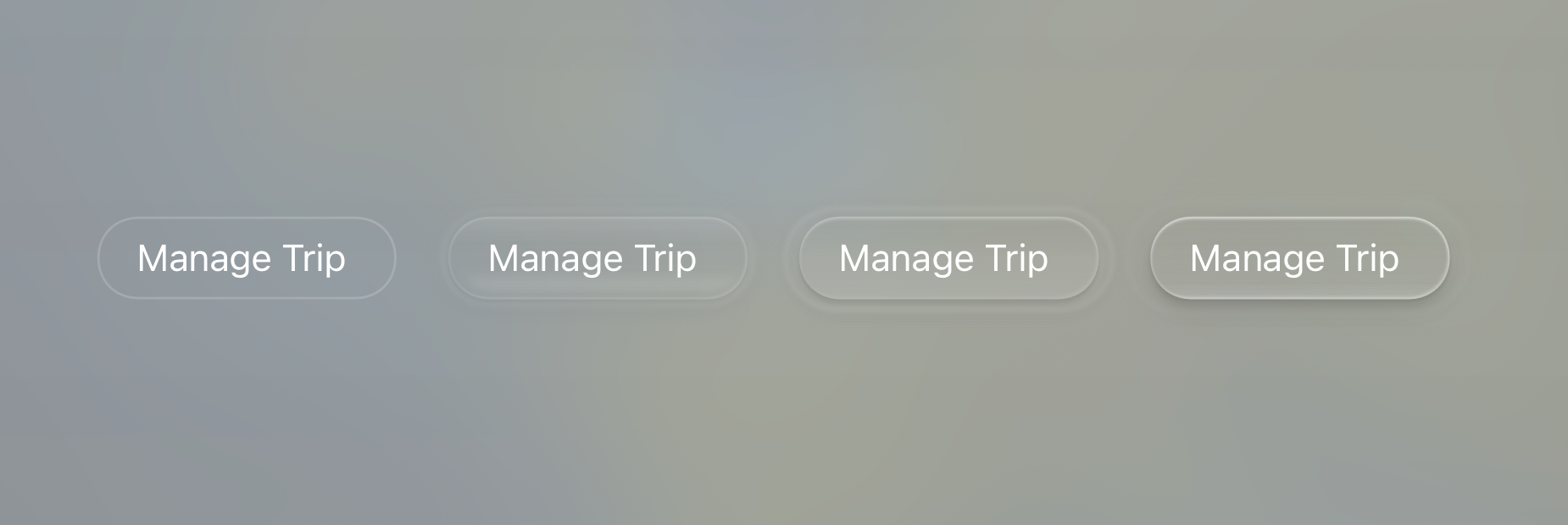

Buttons and other UI elements themselves can get a system-handled treatment much like visionOS handles window treatments.*

*VisionOS is an exceptionally interesting platform, visual effect-wise, as the operating system gets very little data from the device cameras to ensure privacy and security. I would imagine that the “R1” chip, which handles passthrough and camera feeds, composes the glass-like visual effects on the UI chrome. All Apple devices can do this: they already do system-level effect composition for things like background blurs.

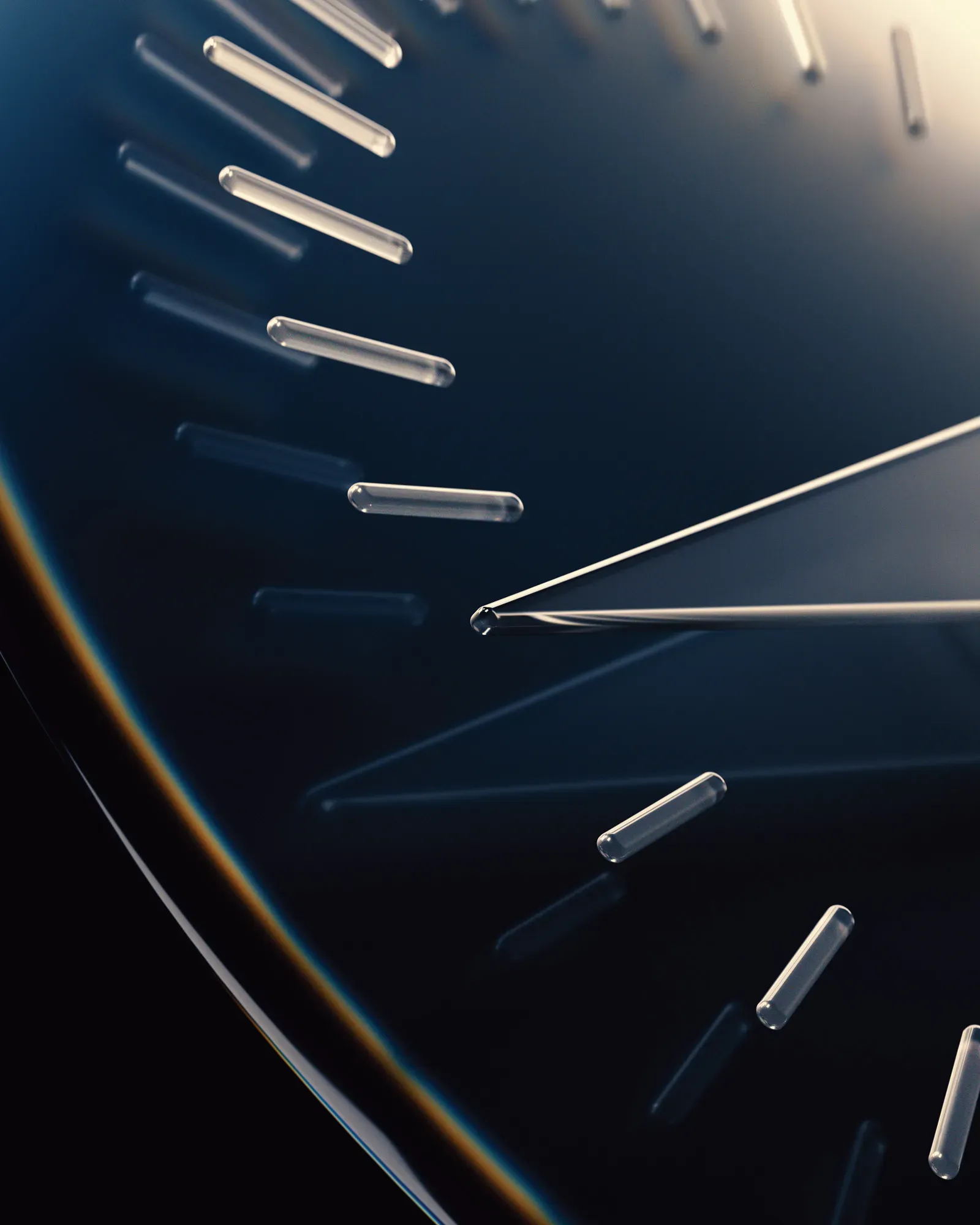

I took some time to design and theorize what this would look like, and how it would work. For the New Design Language, it makes sense that just like on VisionOS, the material of interactivity is glass:

My mockup of a dynamic glass effect on UI controls Glass is affected by its environment. The environment being your content, its UI context, and more.

Since it is reflective, it can reflect what is around it; very bright highlights in content like photos and videos can even be rendered as HDR highlights on Glass elements:

Note the exhaust flare being reflected in the video playback bar; an interactive element like the close button in the top left has its highlights dynamically adjusted by the scene, too. Glass elements visibly occupy a place in a distinct spatial hierarchy; if it does not, elements can be ‘inlaid’: in essence, part of the plane of glass that is your display or a glass layer of the UI:

Much like the rear of your iPhone being a frosted pane of glass with a glossy Apple logo, controls or elements can get a different material treatment or color. Perhaps that treatment is even reactive to other elements in the interface emitting light or the device orientation — with the light on it slightly shifting, the way the elements do on VisionOS when looked at.

Controls may transition as they begin to overlay content. One can imagine animated states for button lifting and emerging from their backdrop as it transitions the hierarchy:

These effects can be rendered subtly and dynamically by the system. In comparison, it makes ‘regular’ static interfaces look and feel inert and devoid of life.

Glass has distinct qualities that are wonderful in separating it from content. It can blur the material below it, as we already see in modern iOS controls. It can have distinct, dynamic specular highlights from its surroundings:

A little drag control for exposure, as a spin on our modern EV adjustment in Halide. Note the material itself responding to the light the adjustment emits. It can have caustics, which is to say it separates itself from the backdrop by showing interaction with light in its environment by casting light, not shadow:

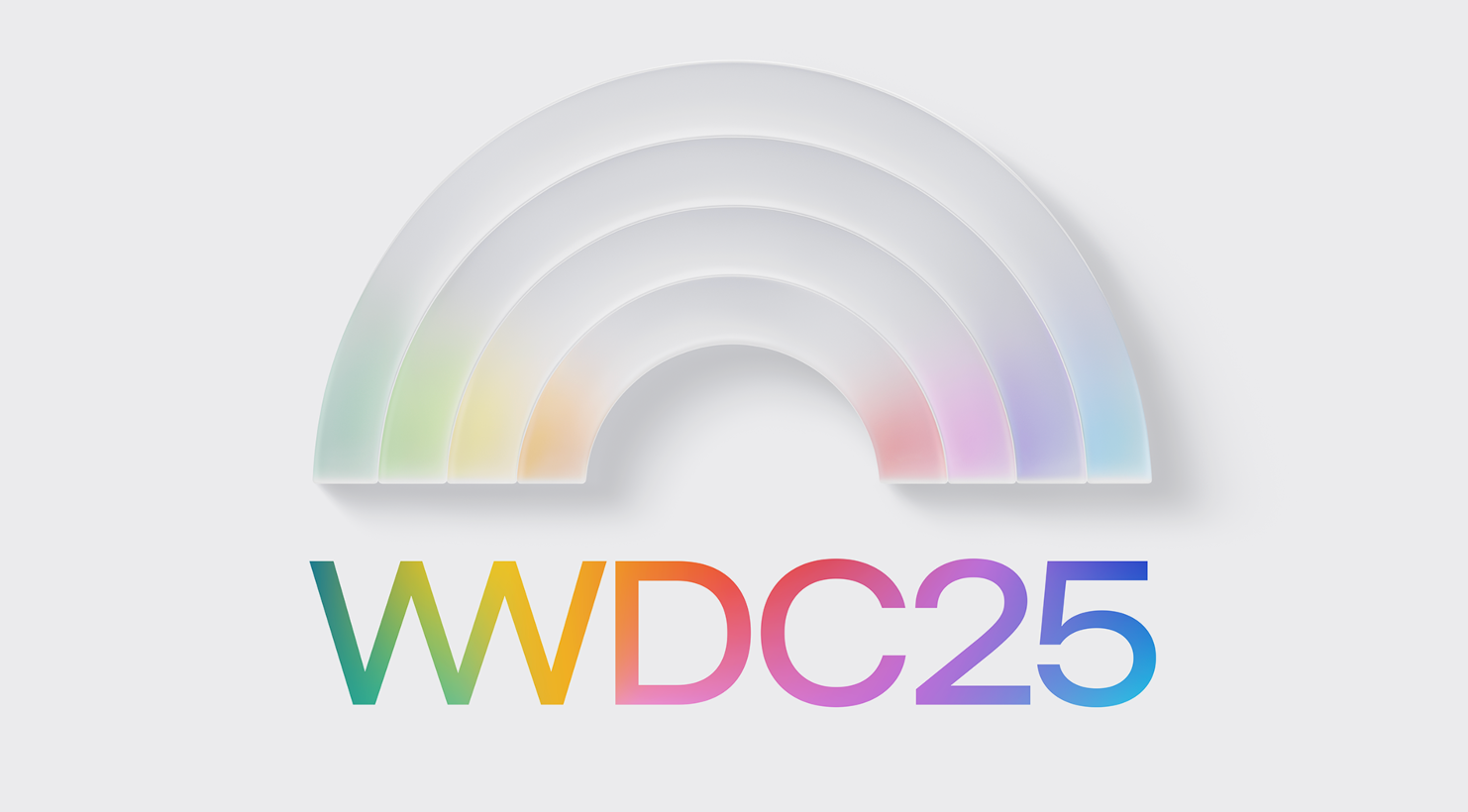

… and it can also get infused with the color and theme of the interface around it. Glass does not just blur or refract its background: it reflects, too. This isn’t totally out of left field: this is seen in the WWDC25 graphics, as well:

Elements of Style

Having a set of treatments established, let’s look at the elements of the New iOS Design.

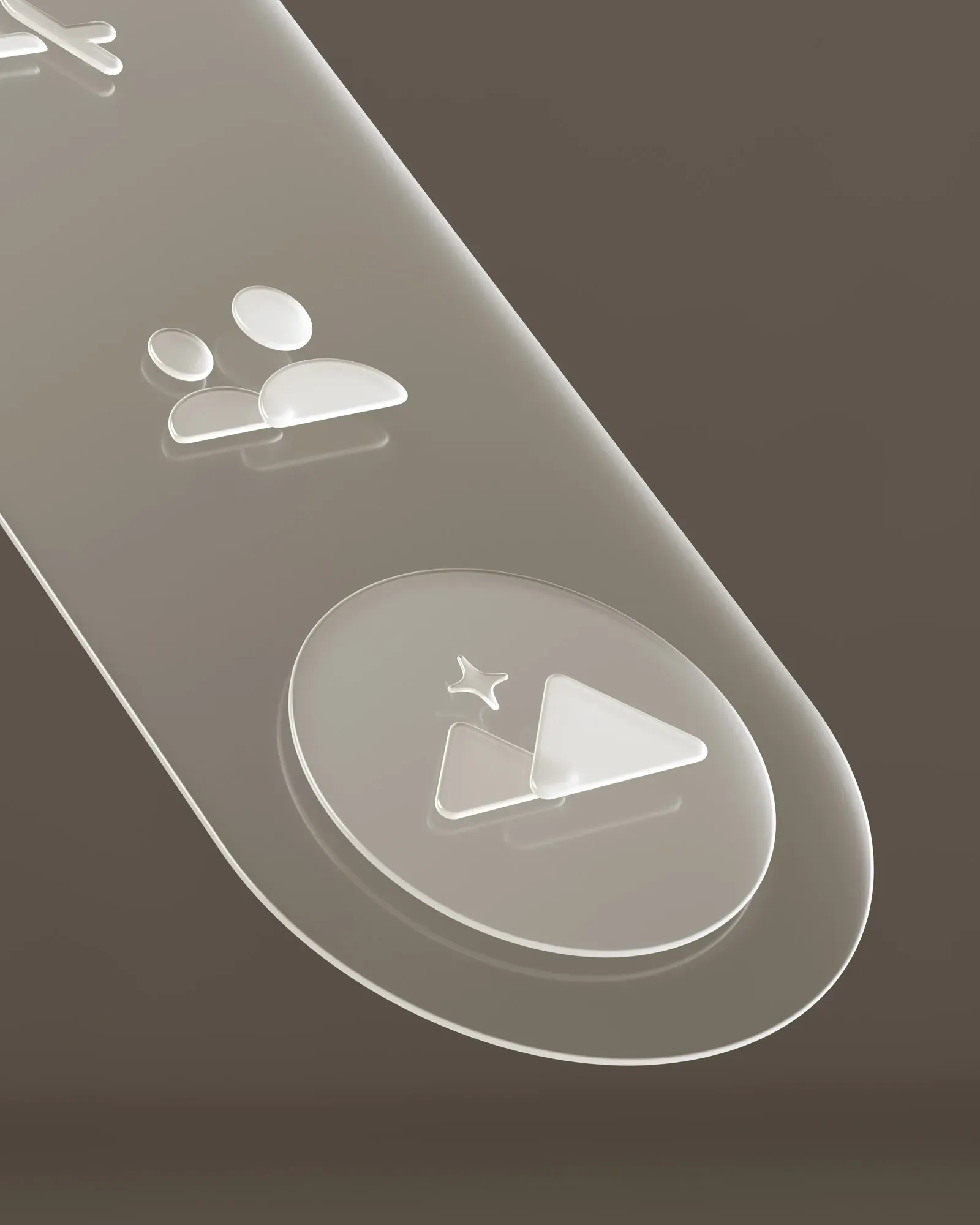

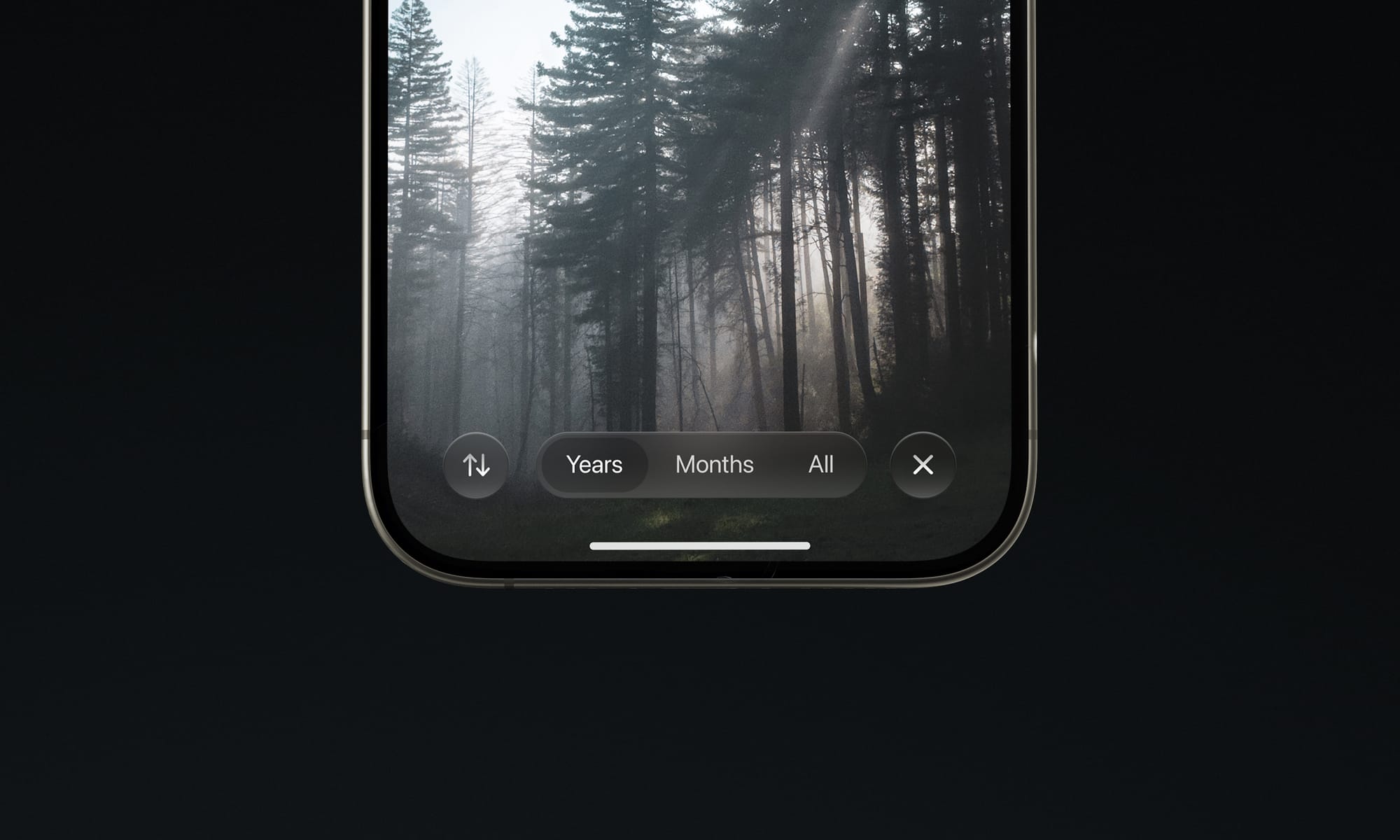

Tab Bar

I would imagine that the era of ‘closed tab bars’, that is, the type that masks the content outright is ending. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if almost all UI that outright masks the interface like that as a max-width bar would be gone.

These types of static interface panels are a legacy element from the early days of iOS. The new type can float over content:

Controls like this are better suited to transition to rise from its underlying ‘pane’ as you scroll it out of view, and can similarly also hide themselves so they’re not obscuring content all the time.

Controls

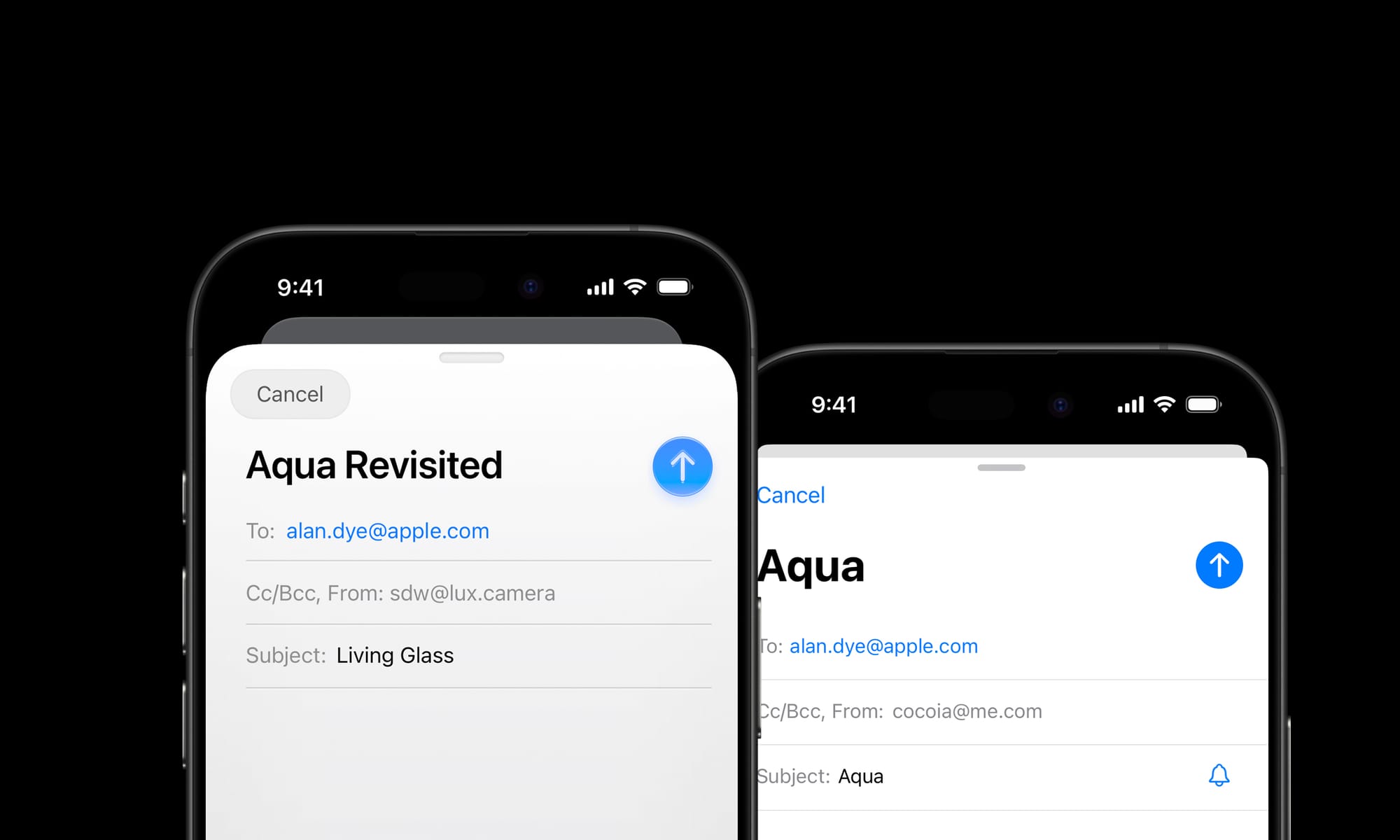

It can be overwhelming for all elements in the interface to have a particularly rich treatment, so as I mentioned before, I would expect there to be various levels of this ‘depth’ applied. Core actions like the email sending button in Mail can be elevated:

Whereas other actions that are part of the same surface — like the ‘Cancel’ action here — can get more subtle treatments.

Elevated controls can be biased slightly towards warmer color balance and background elements towards cool to emphasize depth.

App Icons

Apple put considerable work into automatic masking for icons in iOS 18, and I doubt it was only for Dark Mode or tinted icons on an identical black gradient icon backdrop. The simple, dark treatment of icon backgrounds makes me imagine it was preparation for a more dynamic material backdrop.

Dynamic icon backdrops in Dark Mode – note the variable specular highlights based on their environment. Not to mention, app icons are exactly the type of interactive, raised element I spoke of before that would be suited to a living glass treatment.

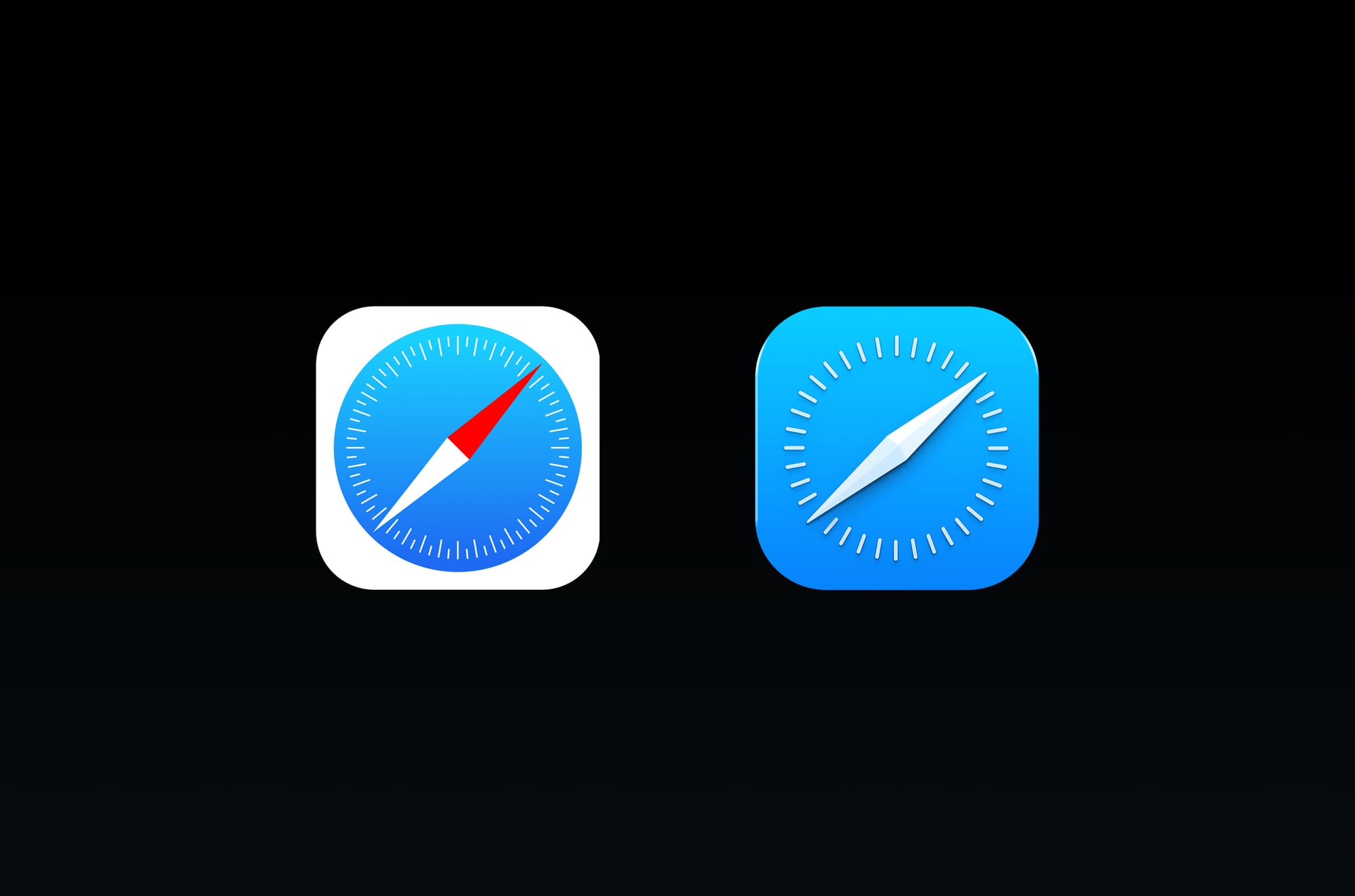

Dynamic rendering of icons with a ‘content layer’, glassy effects and an overall polishing of existing designs. The corners are also slightly rounder. I’d also imagine some app icons that are due for a redesign would get updates. Many haven’t been updated since iOS 7. This would be a major change to some of Apple’s ‘core brands’, so I expect it to be significant, but consistent with the outgoing icons to maintain continuity while embracing the new visual language —kind of like the Safari icon above.

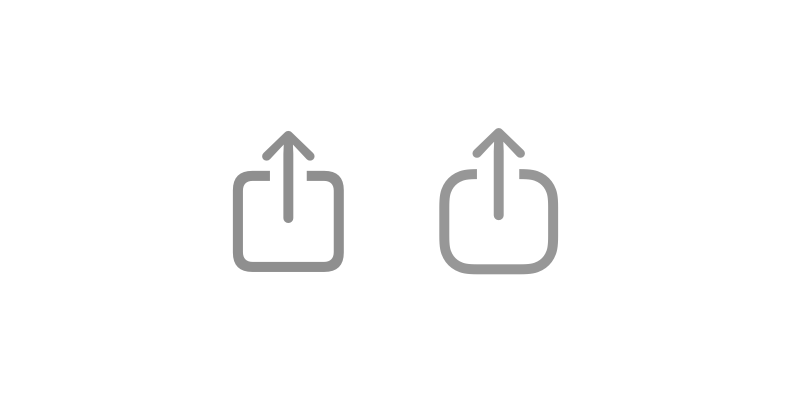

On the note of icons, I also wouldn’t be surprised if the system icons themselves got a little rounder.

Home Screen

It seems likely the Home Screen as a whole is re-thought for the first time. Its complexity has ballooned since the early days of iOS. I find myself spending a lot of time searching in my App Library.

I think there’s a great AI-first, contextual slide-over screen that can co-exist with the regular grid of apps we are used to. I was a bit too short on time to mock this up.

Sliders and Platters

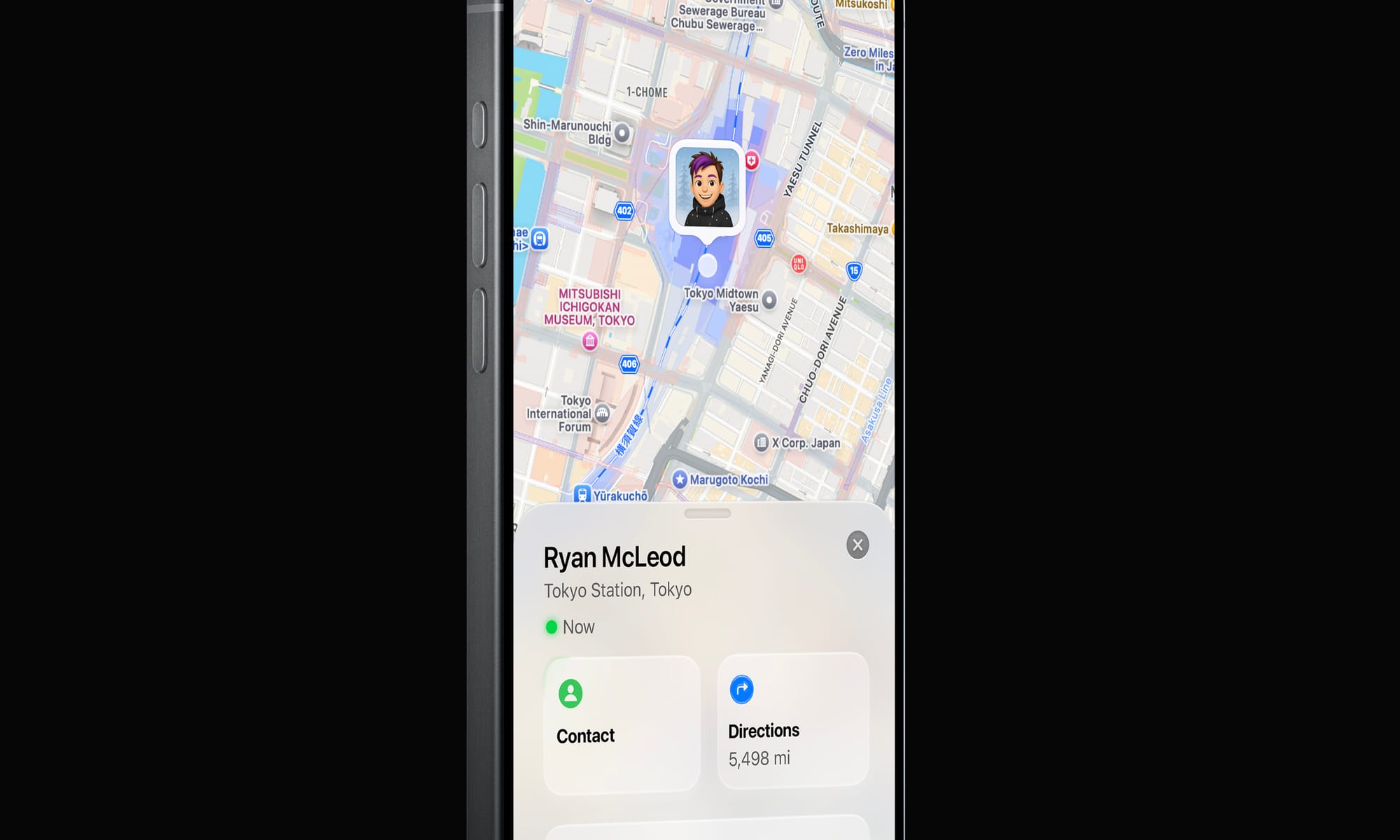

Basic interactive building blocks of the iOS interface will get system-provided treatments that are responsive to their environment:

Note how the Contact platter has some environment interaction with the green ‘Now’ light Overall, one can imagine a rounding and softening of the interface through translucent materials looking pretty great.

Beyond

This ‘simple’ change in treatment — to a dynamic, glassy look — has far-reaching consequences.

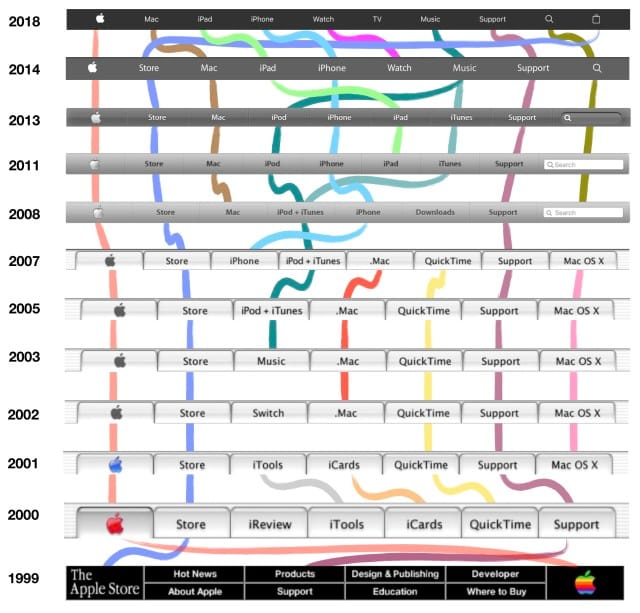

Apple is unique — its predominant user interface style in the 2000s has always been linked to its branding. Its icons are also logos, its treatments a motif that stretch far beyond platforms they live on. Consider the navigation of Apple.com:

The navigation of Apple’s website has changed in step with major UI design eras. The introduction and maturation of Aqua in 2000 and beyond; iPhone and Mac OS X’s softer gradients in 2008; and finally, a flatter look after 2014. It is not a stretch to assume that this, too, would assume some kind of dynamic, new style. Therein lie some of the challenges.

I love products with innovative, novel interfaces — modern iOS isn’t a simply a product, but a platform. Its designers bear responsibility to make the system look good even in uncontrolled situations where third party developers like myself come up with new, unforeseen ideas. That leaves us with the question of how we can embrace a new, more complex design paradigm for interfaces.

A great thing that could come from this is new design tools for an era of designing interfaces that go so far beyond placing series of rounded rectangles and applying highly limited effects.

When I spoke of designing fun, odd interfaces in the ‘old days’, this was mostly done in Photoshop. Not because it was made for UI design — quite the contrary. It just allowed enough creative freedom to design anything from a collection of simple buttons to a green felt craps table.

Green felt, rich mahogany, shiny gold and linen in the span of about 450 pixels. If what is announced is similar to what I just theorized, it’s the beginning of a big shift. As interfaces evolve with our more ambient sense of computing and are infused with more dynamic elements, they can finally feel grounded in the world we are familiar with. Opaque, inert and obstructive elements might occupy the same place as full-screen command line interfaces — a powerful niche UI that was a marker in history, passed on by the windowed environment of the multi-tasking, graphical user interface revolution.

Science Fiction and Glass Fiction

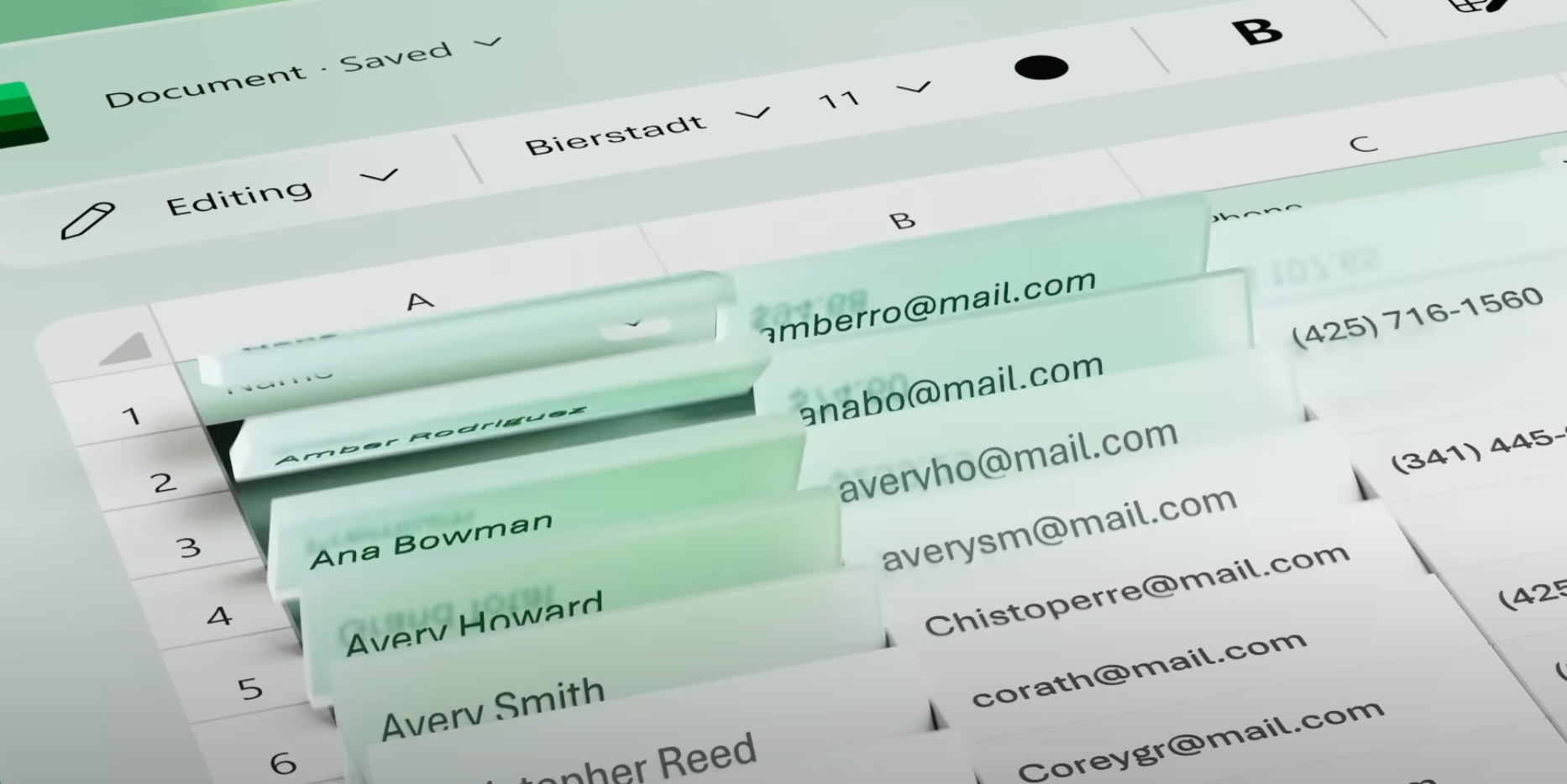

The interfaces of computers of the future are often surprisingly easy to imagine. We often think of them and feature them in fiction ahead of their existence: our iPhone resembles a modern Star Trek tricorder; many modern AI applications resemble the devices in sci-fi movies like ‘Her’ and (depressingly) Blade Runner 2049. It’s not surprising, then, that concept interfaces from the likes of Microsoft often feature ‘glass fiction’:

It’s a beautiful, whimsical UI. Unfortunately, it only exists in the fictional universe of Microsoft’s ads.

The actual interface is unfortunately not nearly as inspired with such life and behavioral qualities. The reason is simple: not only is the cool living glass of the video way over the top in some places, but few companies can actually dedicate significant effort towards creating a hardware-to-software integrated rendering pipeline to enable such UI innovations.

Regardless, we like to imagine our interfaces being infused with this much life and joy. The world around us is — but our software interfaces have remained essentially lifeless.

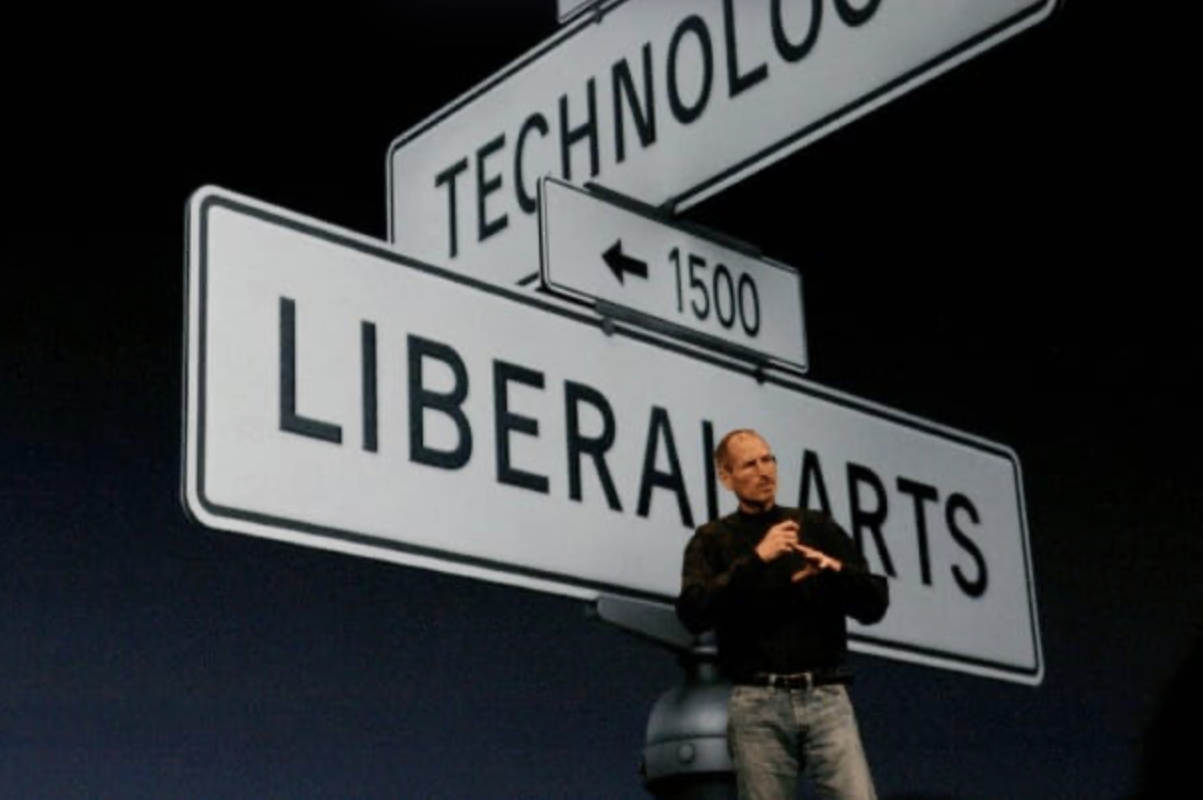

And that brings us to Apple. There was an occasion or two where Apple announced something particularly special, and they took a beat on stage to pause and explain that only Apple could do something like this. It is a special marriage of hardware, and software — of design, and engineering. Of technology and the liberal arts.

And that still happens today. Only Apple could integrate sub pixel antialiasing and never-interrupted animations on a hardware level to enable the Dynamic Island and gestural multi-tasking; only Apple can integrate two operating systems on two chips on Vision Pro so they can composite the dynamic materials of the VisionOS UI. And, perhaps only Apple can push the state of the art to a new interface that brings the glass of your screen to life.

We’ll see at WWDC. But myself, I am hoping for the kind of well-thought out and inspired design and engineering that only Apple can deliver.

All writing, conceptual UI design and iconography in this post was made by hand by me. No artificial intelligence was used in authoring any of it.

-

Rewrites and Rollouts

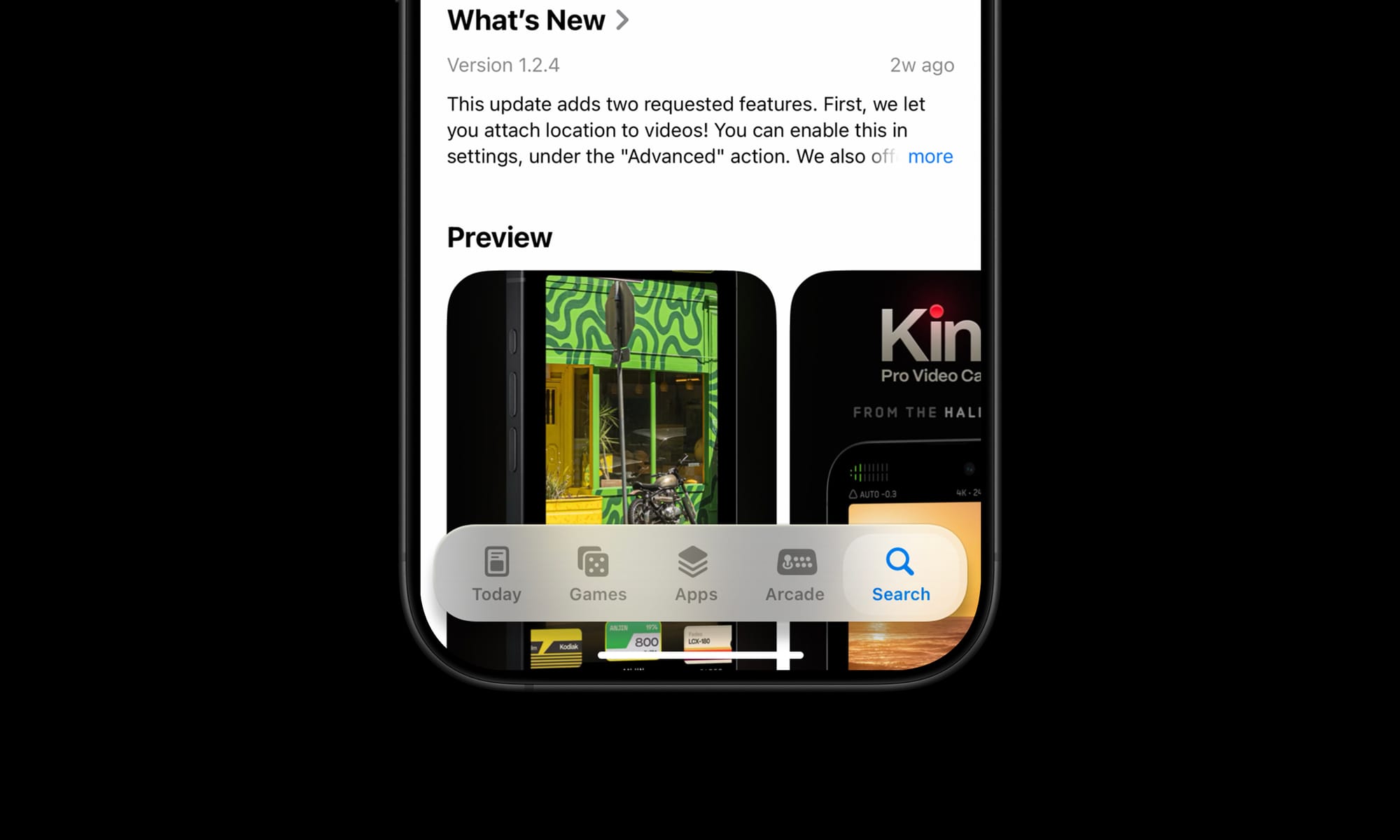

iOS 26 is here. Every year we release major updates to our flagship apps alongside the new version of iOS, but not this year. Rather than stay silent and risk Silkposts, let’s share our thoughts and plans.

Deciding When It’s Time to Move On

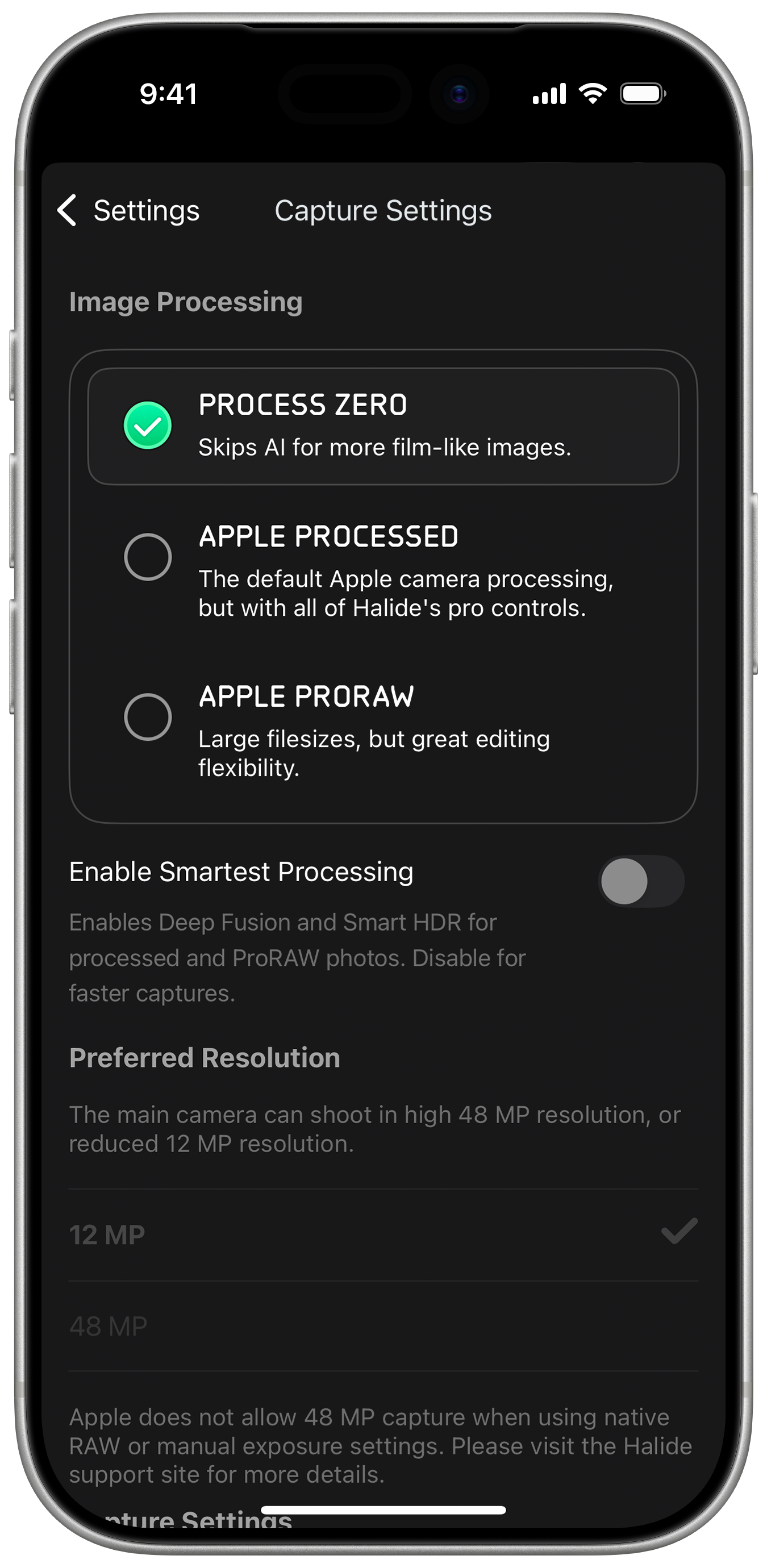

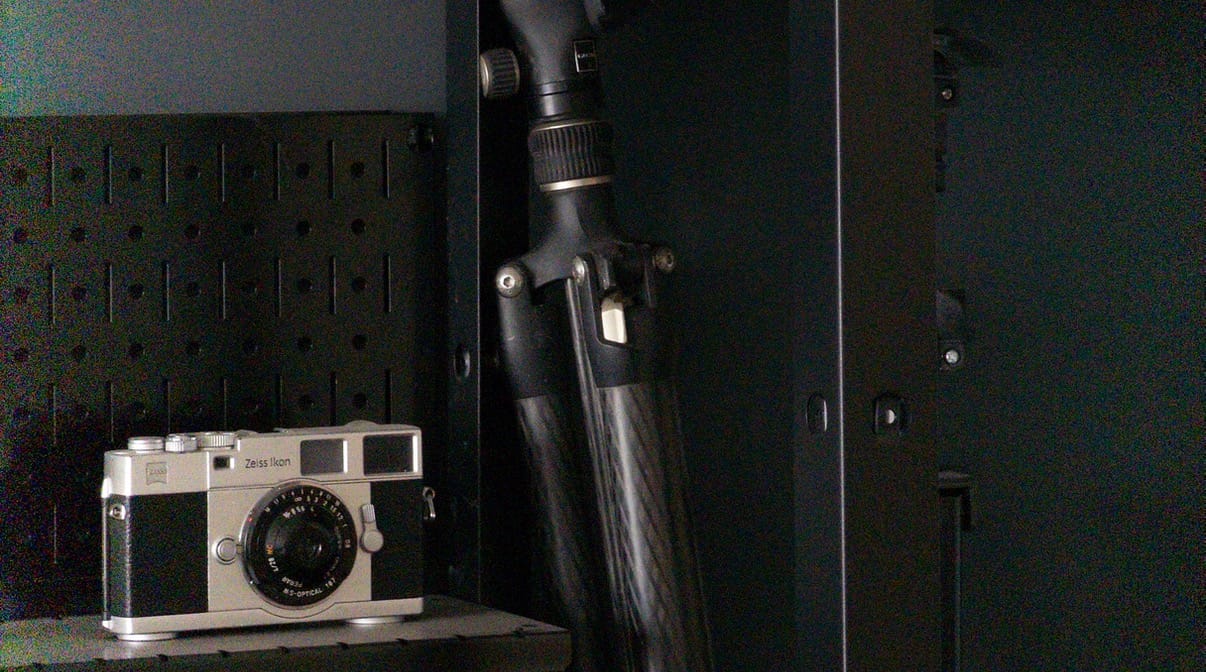

In 2017 we launched the first version of our pro camera, Halide. In those days, the days of the iPhone 7, you just wanted manual control over focus, shutter speed, white balance… controls you expect in a classic camera.

Today, algorithms matter as much as a camera’s lens. Halide kept up with changing times by offering control over these algorithms, and it became one of our most popular features, but we have to admit we aren’t happy with how things evolved, with too many controls tucked away in settings.

This is getting busy. How did things get so complicated?

Our app grew organically from its 1.0, and while we still love its design, we believe it will hit a bit of an evolutionary dead-end. Almost 10 years later, cameras and the way we take photos have changed a lot. We have big plans, and if we’re going to be build the best camera for 2025 and beyond, we need to rethink things from the ground up.

For example, rather than bury the controls from earlier in settings, what if we put them right next to the shutter?

A change like this may sound simple, but these changes have ripple effects across our entire interface and product. I’ll spare you a few thousand words and leave Sebastiaan to walk you through our big new design sometime soon.

If our visuals show cobwebs, let’s just say the code hosts a family of possums. Since 2017, Apple’s SDKs changed faster than we could keep up. Refreshing our codebase should improve speed, reliability, polish, and cut down the time it takes to ship new features.

It sure sounds like we should rewrite Halide.

If you’ve ever taken part in a rewrite, I know your first reaction is, “Oh no,” and as someone who lived through a few big rewrites, I get it. Big rewrites kill companies. It’s irresponsible to do this in the middle of iPhone season, the time we update our apps to support the latest and greatest cameras.

So we are not rewriting Halide right now.

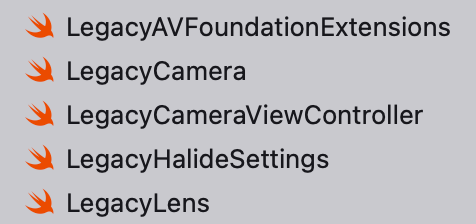

We rewrote it two years ago.

In Summer 2023, we began our investigation into a modern codebase. We built a fun iPad monitor app, Orion, test the maturity Apple’s new frameworks and experiment on our own new architecture. We were delighted by the results, and so were you! We were surprised Orion only took 45 days.

This gave us the confidence to test our platform on a bigger, higher-stakes project: our long-awaited filmmaking app Kino. We began work in Fall 2023, shipped in under six months, and won 2024 iPhone App of the Year.

record scratch yep, that’s me. You’re probably wondering… This signaled our new architecture was ready for prime time, so earlier this year, we drew a line in the sand. In our code, we renamed everything Halide 2.x and earlier, “Legacy Halide.” Mark III will be a clean break.

A few files in Xcode After a few weeks of knocking out new features faster than ever, it was clear this was the right decision. Kino let us skip over the hard and uncertain part, and now all that’s left is speed-running the boring part of translating the old bits to the new system.

Through The Liquid Glass

In June, Apple unveiled the new design language of iOS 26, Liquid Glass, and it threw a monkey wrench in all of our plans. As someone who worked on a big app during the iOS 7 transition, I know platform rewrites are wrought with surprises all the way up to launch.

Before we decided how to proceed with our flagship apps, and its effects on Mark III, we need to investigate. So we returned to Orion, our low-stakes app with fewer moving parts. Updating Orion’s main screen for liquid glass took about a day, but it was not without snags, like when I spent an hour in the simulator fine tuning the glass treatment of our toolbar only to discovered it rendered differently on the actual device.

We moved on to Kino, which already aligned with the iOS 26 design system pretty well. Sebastiaan updated its icon treatment, which looks great when previewed in Apple’s tools.

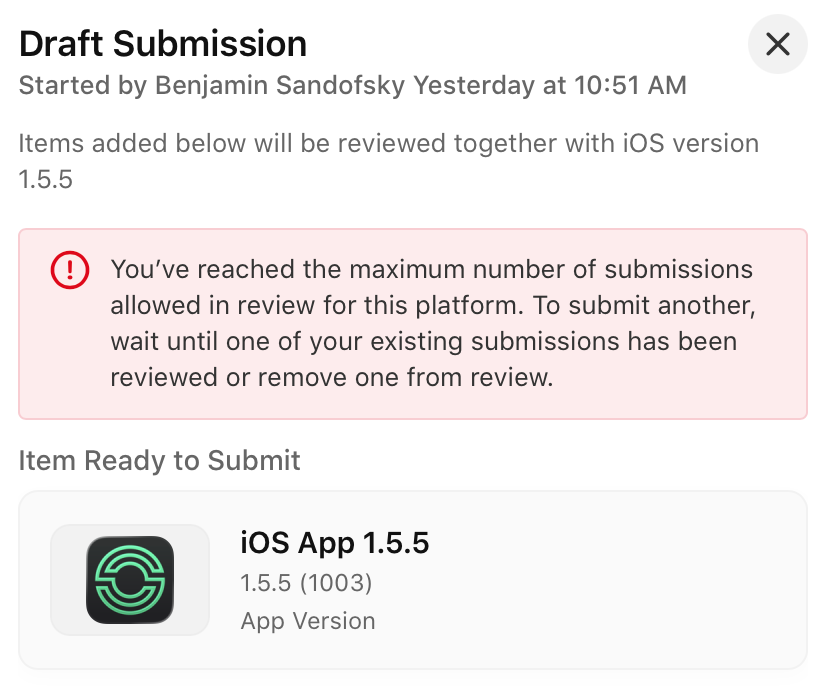

The version previewed on Icon Composer However, when we loaded it on the device…

The version on a real device This issue still persists in the final version of iOS 26, and filed a bug report with Apple (

FB20283658). We’ll hold off on our Kino update until it’s sorted out.None of these issues are insurmountable, but troubleshooting iOS bugs for Apple can be its own part-time job. As a team with only one developer, this left us with three options for Halide:

Option 1: Embrace Liquid Glass in Legacy Halide. Liquid Glass paradigms go beyond the special effects, such as its embrace of nested menus. Reducing the new design system to a stylistic change— a glorified Winamp skin— is a recipe for disappointment. Unfortunately, a deep rethinking of legacy Halide would force us to halt Mark III development for months, just to update a codebase on its way out.

Option 2: Rush Mark III with Liquid Glass to make the iOS 26 launch. Even before Apple unveiled the Liquid Glass treatment, Mark III was arriving at similar concepts. We’re confident that the two design systems will fit well together. So what if we tackle both challenges at once, and target an immovable iOS 26 deadline? Nope. A late app is eventually good, but a rushed app is forever bad.

Option 3: Wait to launch a full Liquid Glass redesign alongside a rock solid Mark III. This is what we did, and we think it paid off big time. Earlier this week we released an early preview of our new UI (without any liquid glass) to Halide subscribers via our Discord. The results were overwhelming positive.

The Rollout (and early upgrade perks)

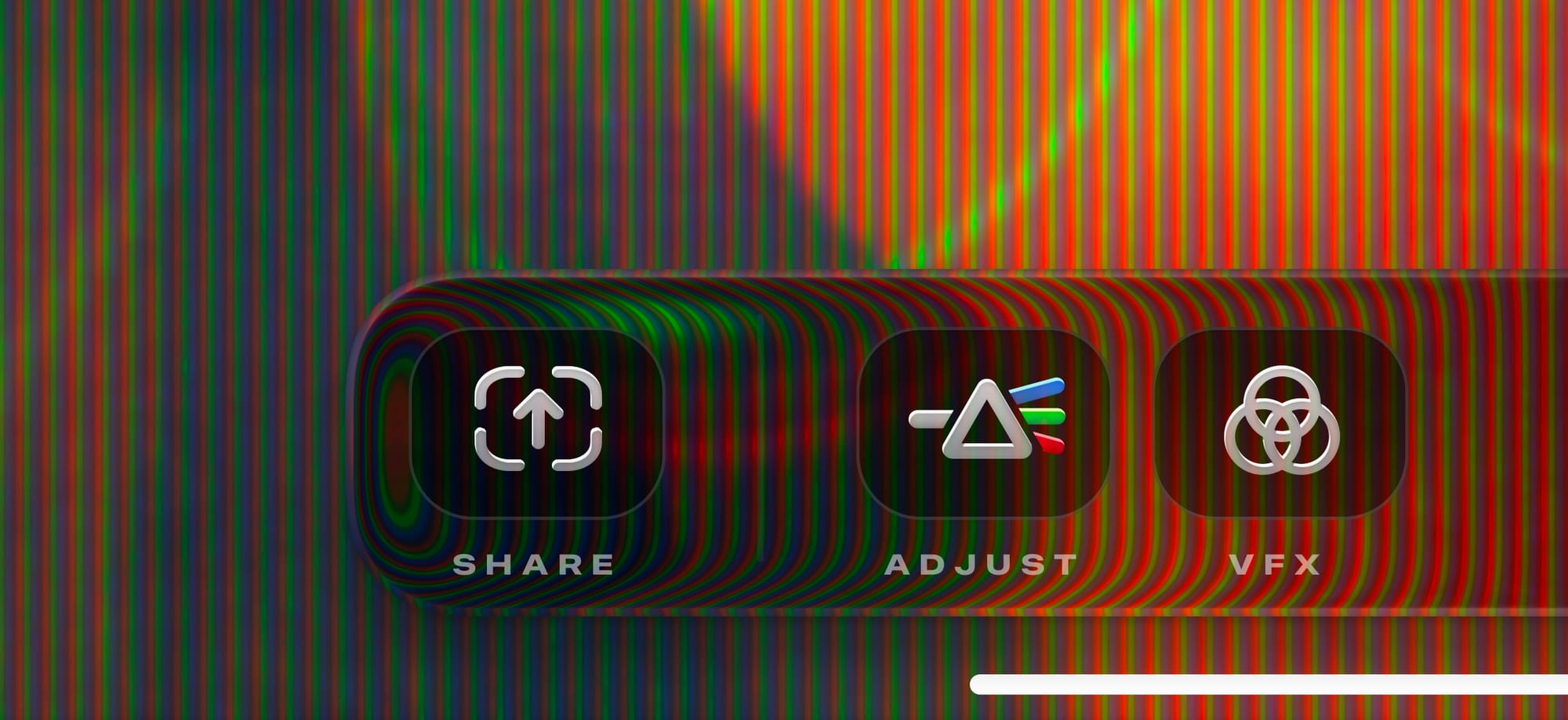

That’s not to say we have nothing to show for iOS 26. Today we’re launching Orion 1.1. It retains most of its retro aesthetics, but we’re also digging how the liquid glass treatment interacts with our custom CRT effect.

We’ve also added a long-requested feature: fit and fill, for aspect-fill ratios. You can finally play your virtual console games in full screen glory!

For Kino, we’re holding off on our update until we sort out the iOS bugs. Maybe things will be fixed in an iOS 26.1 update.

We have an update ready for our award winning long exposure app, Spectre. Unfortunately, it appears the App Store portal is broken at the moment, and won’t allow us to submit the update.

Luckily, we submitted an update to Halide before running into this issue. It updates the icon, fixes a few glitches, and includes basic stylistic updates. We just released this update, moments ago.

Earlier today, we received our new phones and we’ve begun running them through the paces. We’ll submit an update to support the new hardware and fix any bugs, assuming the App Store lets us.

These updates to Halide are a swan song for the legacy codebase. After this month, all of our energy goes Mark III, which includes the real Liquid Glass alongside a redesigned camera for a new age.

If you’d like a peek at things to come, we’ve opened another thousand spots in TestFlight to Halide subscribers. It’s got tons of bugs, and parts are incomplete, but will give you an idea of where things are headed. If you’d rather wait for a polished experience, or prefer a one-time-upgrade, no problem. As we announced last winter, everyone who bought Mark II eventually gets Mark III for free.

It feels bittersweet moving on. Hopping into Legacy Halide to crank out updates feels a bit like a slog, while the new Mark III design and codebase is a joy. It makes me wish I wish I’d gutted Halide years ago. At the same time, there are moments I feel warmth for a project where I spent almost a decade of my life. It helps you understand why nostalgia means, “A pain from an old wound.”

In Summary

- We have an Orion update out, today

- We have a Spectre update, soon

- We might have a Kino update, soon?

- We have a Halide update, today

- Halide Subscribers can sign up for the Mark III TestFlight, today

- We’ll have a wider Mark III preview, this Fall

- If everything goes according to plan, we expect to launch Mark III, this Winter

This won’t be the last you’ll hear from us this Fall. Stay tuned for a post from Sebastiaan on our new design, along with our annual iPhone reviews.

-

iPhone 17 Pro Camera Review: Rule of Three

Every year I watch the Apple Event where Apple announces the latest iPhones, I can’t help but sympathize with the Camera team at Apple. They have to deliver something big, new, even ground-shaking, on a regular annual cadence.

And every year, people ask us the same thing: is it really as big of a deal as they say?

iPhone 17 Pro in Silver — shot on iPhone Air

iPhone 17 Pro looks very different at first glance. It’s the biggest departure from the style of camera module and overall Pro iPhone style since iPhone 11 Pro. It still packs three cameras on the back and one on the front. It has an actual camera button (even its svelte sibling, the iPhone Air gets one of those, albeit smaller) and a few notable spec changes, like a longer telephoto zoom. Or is it? And is that really all there is to it?

To find out, I took iPhone 17 Pro to New York, London and Iceland in just 5 days.

We do not get early access like the press: this is a phone we bought, to give you an unfiltered, real review of the camera. All the photos in this review were taken on iPhone 17 Pro, with the Apple Camera app or an in-development version of Halide Mark III with color grades.

Let’s dig in — because shooting with iPhone 17 Pro, I was surprised by quite a few things.

What’s New

iPhone 17 Pro packs what Apple calls the new ‘ultimate Pro camera system’. This is the last upgrade the camera bump — er, I mean, plateau — was arguably still lacking.

After its introduction with iPhone 11 Pro, all cameras were shooting at a fairly standard 12 megapixels. After the ultra wide camera was upgraded to 48 megapixels in iPhone 16 Pro, Apple finally upgraded the telephoto camera sensor to a 56% larger unit with 48 megapixels. Not only does this allow for sharper shots, but Apple is so confident in its center-crop imaging pipeline that it argues it allows for a 12-megapixel 8× zoom of ‘optical quality’. More on that one in its own, detailed section: I am a big telephoto fan, and this announcement had me immediately excited to test it out.

One of the biggest upgrades this year actually comes to the front camera — but its quality impacts will be far less noticeable to most people than most tech pundits initially predicted. In a classic Apple move, the company replaced the bog standard selfie camera with a much larger square-sensor packing camera, but instead of now simply shooting 24 megapixel square shots it added a very clever Center Stage system to reframe your selfie shots to include people into it automatically or save you from twisting your arm to take a landscape selfie shot.

Apple’s square sensor makes it part of a small elite lineup of square sensor cameras like the latest Hasselblad 907X This is a very impressive piece of engineering, and a classic Apple innovation in that the hardware change is essentially invisible. Us camera geeks love the idea of a square sensor, but in the Camera you will not find a way to take images with the full square image area; it just puts the square area of the 24MP sensor to use for 18 MP crops in their landscape or portrait depending on the subject matter.

Apple (in my opinion, correctly) figured that if this artistic choice being made by your iPhone offends you as an artist, you are free to use one of the better cameras on the rear of the iPhone or disable the automatic framing feature altogether, returning its behavior to a ‘normal’ front-facing selfie camera.

Finally, there’s some notable changes to processing. “More detail at every zoom range and light level”. In particular, Apple stated in its keynote that deep learning was used for demosaicking raw data from the sensor’s quad pixels to get more natural (and actual, existing) detail and color in every image. In particular, Apple went to point out this also meant that its AI upscaling that’s used to make those ‘2×’ and ‘8×’ ‘lenses’ (that are actually the center portion of the 48MP Main and Telephoto cameras) is significantly improved.

Finally, and not insignificantly, the entire phone has gotten a total design overhaul. Its interface and exterior are both composed of all new materials, and some big changes under the hood (or ceramic back panel, if you will) allow for even more performance out of the latest generation Apple Silicon chip inside.

What’s Not New

While the entire iPhone looks brand new, the cameras have some familiar parts. The Main camera sensor and lens is identical to the iPhone 16 Pro’s, which in turn is identical to the iPhone 15 Pro’s. The ultra wide camera, too, is the same as last year’s 48 megapixel snapper.

The Ultra Wide camera returns to continue making wide, sweeping compositions The Camera Control from iPhone 16 Pro returns on all iPhone 17s and iPhone Air. No significant updates here, but I still find it a fantastic addition to the iPhone for opening my choice of camera app and taking a photo. The adjustments, on the other hand, still seem fiddly to me a year later. I was hoping for some more changes to it, perhaps even a face lift along with iOS 26 — but it has remained essentially the same save for some additional settings to fine-tune it to your liking.

Party in the Front, Business in the Back

This is, without a doubt, a great back camera system. With all cameras at 48MP, your creative choices are tremendous. I find Apple’s quip of it being ‘like having eight lenses in your pocket’ a bit much, but it does genuinely feel like having at least 5 or 6: Macro, 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 4× and 8× .

The — unchanged save for processing tweaks — ultra wide and main camera are still great. I find the focal lengths ideal for day-to-day use and the main camera especially is sharp and responsive. Its image quality isn’t getting old (yet).

What’s beginning to get very old is its lack of close focusing. Its new sibling camera in iPhone Air focuses a whole 5 cm (that’s basically 2 inches) closer, and it’s very noticeable. For most users, arms-length photography is an extremely common use case: think objects you hold, a dish of food or an iced matcha, your pet; you probably take photos at this distance every day. And if you do, you’ll have encountered your iPhone switching, at times rapidly, between the ultra wide ‘macro’ lens and the regular main camera — one of which produces nice natural bokeh and has far higher image quality. It’s been several years of this now, and it’s time to call it out as a serious user experience annoyance that I hope can be fixed in the future. This is, incidentally, one of the reasons why our app Halide does not auto-switch lenses.

We love a good 2× lens

Shooting at 2× on iPhone 17 Pro did produce noticeably better shots; I believe this can be chalked up to significantly better processing for these ‘crop shots’. Many people think Apple is dishonest in calling this an ‘optical quality’ zoom, but it’s certainly not a regular digital zoom either. I am very content with it, and I was a serious doubter when it was introduced.

The entire camera array continues to impress every year in working in unison: this year, more than ever, my shots were very well color and color temperature matched and zooming was more smooth between lenses than I’d seen.

It’s wild that they pull this off with 3 different camera sensors and lenses. It’s essentially invisible to the average user, and that’s a real feat. No other company does this as well: pick up an Android phone and go through their copy of the iOS Camera zoom wheel to see for yourself sometime.

4× the Charm

I have previously written perhaps one too many love letter to the 3× camera lens that the iPhone 13 Pro, 14 Pro had. While it had a small sensor, its focal length was just such a delight; one of my favorite go-to lenses is 75mm. Shooting with longer lenses is a careful balance of framing, and it’s harder the longer the focal length is.

I had to actually think about achieving a nice scene here with the telephoto lens, rather than the ultra-wide’s ‘shoot my view’ approach.

Creative compositions are much easier when you have to select what not to include rather than to focus attention on one thing; the devil is in the detail.

Satisfying compositions are everywhere if you start looking for them. Here’s a bridge vs. bridge shot. The previous iPhone traded some image quality in the common zoom range (2-4×) for reach. I found the 16 Pro’s 5× lens reach spectacular, but creatively challenging at times for that reason. There was also a tremendous gap in image quality between a 3× – 4× equivalent crop of the Main camera and the telephoto, which made missing an optical lens at that range even more painful.

4× is an elegant solution; while I do still miss 3× — 3.5× would’ve been perfect, but admittedly not nearly as numerically satisfying as 1-2-4-8× — the lens’ focal length is fantastic for portraiture and details alike, and its larger sensor renders impressive detail:

Even in low light, the lens performs admirably — due to a multitude of factors: excellent top-tier stabilization of the sensor 3D space, software stabilization, good processing and a larger sensor.

It is still is very much reliant on processing and Night Mode compared to the Main camera, however — expect those nighttime shots to require ProRAW and / or Night Mode to get the most out of a shot.

This is a pretty significant improvement over the way the previous 5× lens handled a dark scene.

Even then, things will look fairly ‘smoothed over’:

Detail in the buildings here is entirely smoothed over by noise reduction. It’s a larger sensor, but a long lens and still relatively small sensor just means noisy images at night, which shows up as heavy noise reduction in the shadows.

Regardless, this is a tremendous telephoto upgrade, and if you were as much of a telephoto lover as me it might well be reason alone to upgrade.

Are the 48 megapixel details truly visible? Well, judge for yourself:

I find that the resolution is great, though the lens is a bit soft.

I found that the softness of the lens and its lack of heavy handed sharpening in post (at least in Halide’s Process Zero or Camera’s ProRAW capture mode) felt downright atmospheric. You can always add heavy sharpening later if you want that effect.

I like this softness, myself; it is to Apple’s great credit that there isn’t some kind of heavy handed sharpening algorithm that pushes these images to look artificially sharper.

It renders very naturally, extremely flattering for portraiture, and showcases processing restraint that I haven’t seen from many modern phone makers. Bravo.

It also has an additional trick up its sleeve thanks to those extra pixels and processing: an additional lens unlocked by cropping the center 12 MP area of the image, along with some magical processing. Does it really work?

8× Feature’s a Feat

The overall experience of shooting a lens this long should not be this good. I’ve not seen it mentioned in reviews, but the matter of keeping a 200mm lens somehow steady and not an exercise in tremendous frustration is astonishing. Apple is using both its very best hardware stabilization on this camera and software stabilization, as seen in features like Action Mode.

You will notice this while using the camera at this zoom level: the image will at times appear to warp in areas of your viewfinder, or lag behind your movement a little bit. The only way to truly communicate how impressive this is is to grab a 200mm lens and hand-hold it: you’ll find that it magnifies the small movements of your hand so much that it is really hard to frame a shot unless you brace it.

And then there’s the images from this new, optimized center-crop zoom.

To say I’ve been impressed with the output would be an understatement.

Sometimes you get a little bit of a comedic effect as you realize you are seeing things through the telephoto lens you hadn’t even noticed or can’t quite make out with your own eyes:

And other times you become that stereotypical bird photographer (or in my case, a wanna-be). I will note that even with its magical stabilization, getting a picture of something in rapid motion is a bit of a challenge…

… but the results are truly magical if you do nail it. Is this tack sharp?

Well, no, but this is 500% detail of a crop of a phone sensor shooting at 200mm at a fast moving bird on a cloudy day. I am pretty impressed.

It allows for some astonishing zoom range through the entire system.

I mentioned it before, but I want to reiterate it because it’s such a fun creative exercise for anyone with this phone: I believe that the longer the lens, the more of your skills in creating beautiful compositions and photos will be challenged. It’s just not that easy — but it also means you suddenly find different beautiful photos in what was previously a single frame:

The details are often prettier than the whole thing. Now I get to choose what story my image tells. What caught my eye, or what made the moment so magical. In video this is also lots of fun; I will post some Kino shorts on our Instagram to highlight the fun of moving video details of a scene.

Another example: here, Big Ben can take the center stage. As I shoot at 4×, I get an ‘obvious’ composition:

At 8×, I am presented with a choice: I can capture the tower, or the throng of people crossing the bridge and note as the evening sun lights up the dust in the air:

I like what this does for you as a photographer. Creativity, as many things do, can function as a muscle. Training it constantly, and stimulating yourself by forcing creative thought is what helps you become better at the craft.

This is a little artistic composition gym in your pocket. Use it.

Trust the Process

As we mentioned in our last post, algorithms are about as important — perhaps more so — than the lens on your camera today. There’s a word for that: processing. We’re keenly aware of just how many people are at times frustrated with the processing an iPhone does to its imagery. It’s a phenomenon that comes from a place of exceptional luxury: without its mighty, advanced processing an iPhone would produce a far less usable image for most people in many conditions.

I believe the frustration often lies in the ‘intelligence’ of processing making decisions in image editing that you might consider heavy handed. Other times, it might be simply reducing noise that makes an image look smudgy in low light.

Processing makes curious mistakes at times. Here, a telephoto image came out looking a bit mangled. Image processing is the one area where phones handily beat dedicated cameras, for the simple reason that phones have far more processing power at their disposal and need to do more to get a great image from an exceptionally small image sensor. We review it as intensely, then, as a new bit of hardware. How does it stack up this year?

Well, it’s somewhat different.

iPhone 17 Pro above, iPhone 16 Pro below On the Main camera, don’t expect huge changes. I found detail to be somewhat more natural in the Ultra Wide camera, but even here it was somewhat random-seeming if the results were truly consistently better. Overall, image processing pipelines are so complex now that it’s hard to get a great idea of the changes over just a week. The images overall felt a bit more natural to me, though — although I still prefer shooting native RAW and Process Zero shots if I have the option to.

As I mentioned in the earlier section, it is truly noticeable that the 2× mode on the Main camera is a lot better. Not only is the result sharper, it also just looks less visibly ‘processed’; a real win considering Apple claims this is actually due to more processing!

Finally, you might wonder: if these images are a bit better processed and all this being software, why isn’t this simply being rolled out to the older iPhones just the same? Is Apple purposefully limiting the best image quality to just the latest iPhones?

The answer is yes, though not through inaction or some kind of malevolent and crooked capitalist lever to force you to upgrade. Software in itself might be easily ported across devices, but image pipelines like the ones we see on the iPhones 17 Pro are immensely integrated and optimized. It’s quite likely the chip itself, along with hardware between the chip and sensor are specifically designed to handle this series’ unique image processing. Porting it over to an older phone is likely impossible for that reason alone.

Video for Pros

This is mainly a photography review, but I also increasingly shoot video and make an app for it. iPhone 17 Pro has some absolutely wild features for pro video. They put the capital P in Pro; things like Genlock and ProRes RAW are far beyond what even advanced amateur users will likely use.

Video stills of graded Log footage from our app Kino

That being said, these features aren’t just for Hollywood. While it’s true that some of these latest ultra-powerful video pro features will allow the iPhone to become even more of a pro workhorse in terms of capturing shots and become usable in significant productions, the introduction of Apple Log with iPhone 15 Pro and other technologies are really just fuel for developers to run with.

When we built Kino, we wanted to make it so you can actually use things like Apple Log and the Pro iPhone’s video making advancements without an education in the fine art of color grading in desktop software and learning what shutter angle is.

Adding technologies like this not only make the iPhone a truly ‘serious camera’, but since it’s a platform for development, it also creates use cases for these technologies that have not been possible in traditional cameras used for photography and videography.

This is super exciting stuff, and I think we’ll see the entire field evolve significantly as a result. With this set of new features — Open Gate recording, ProRes RAW, Apple Log 2 — Apple is continuing to build an impressive set of technologies that let it rival dedicated cinematic cameras without compromising on the best part of the iPhone: that it’s really a smartphone, which can be anything you want it to be.

A Material Change

Everything’s new on this phone, appearance wise: a return to aluminum is welcome. The new design cools itself much better and that’s noticeable when you shoot a lot. It feels great in the hand and hopefully will age as nicely as my other aluminum workhorses from Apple. Apple even markets it as being especially rugged:

On the other hand, its other user-facing aspect — iOS itself — has also gotten a new material shift.

Liquid Glass is here with iOS 26, and it brings about an entirely new Camera app design, some much desired improvements to the Photos app, and a general facelift to the OS. While this isn’t an iOS review, I will say that it’s beautiful, and I’m a fan of Liquid Glass. iOS 26, however, has been a bit of a rough start: I ran into a lot of bugs even with the latest updates installed on the iPhone 17 Pro, from bad performance (OK) to photos not showing up for a long time to distorted images and the camera app freezing or being unusable (not so OK).

It seems all telephoto images shot in native RAW have this light band artifact on the left side of the frame. Not great. Big releases are ambitious, and difficult to pull off. I give tremendous credit to the teams at Apple for shipping iOS 26 along with these new devices, but in everyday use it truly felt like using a beta release. The constant issues I ran into did not make me feel like I was using a release candidate of an operating system.*

*Feedback reports on these issues have been sent to Apple.

Conclusion

I think the iPhone Air serves a very important purpose: it allows Apple to make one phone a jewelry-like, beautiful device that is like a pane of glass and one that is decidedly like the Apple Watch Ultra: bigger, bulkier and more rugged.

For years, I was a bit annoyed at the shininess and jewel-like qualities of the Pro, and to be entirely honest, I do now miss it a little bit. This is a beast in both performance and appearance, and it feels almost a little unlike Apple. I think, however, that the direction is correct and significant.

Our phones are such a central part of our lives now that it feels significant be able to have a choice for a product that prioritizes the true ‘pro’ — much like MacBook Pro did in a fantastic way with the thicker, bulkier M1 series.

This, then, might be the first ‘workhorse SLR’ of the iPhone family, if the regular iPhone is a simple Kodak Brownie. In that, some of the simplicity that delighted in the first iPhone may have been lost — but the acknowledgement that complexity is not the enemy is a significant and good step. As a camera, it is first and foremost a tool of creative expression: gaining permission to become more fine-tuned for that purpose makes it truly powerful.

It’s left as an exercise to the user to excel at their purpose as much as the phone does.

All images in this review were taken on iPhone 17 Pro (unless otherwise noted). Photos were taken with an in-development version of Halide Mark III with built in grades for adjustment, with a smaller portion taken with Apple Camera in ProRAW and stills from the Kino app using built-in grades for adjustment.