Last week I set out to write a few thousand words on the iPhone Air, but it turns out I only need three: the lesser iPhone. Compared to the Pro and baseline models, it has fewer cameras and a smaller battery. For an extra $100, you can upgrade to an iPhone Pro and get power features like ProRAW and LiDAR. What was Apple thinking?

Every few years, Apple tests a new product category with a “wildcard” iPhone. In 2015, that was a Plus sized screen. In 2017, the iPhone X ditched the home-button and gained a notch. In 2019, the Pro introduced bleeding-edge technology at a premium price point

Some experiments flop. For years, people begged for a smaller iPhone, so Apple delivered the iPhone Mini in 2020 to lukewarm sales. I’d wager it was because, 13 years after the iPhone’s debut, we now use our phones like we used to use computers. The era of small screens is over.

From the mini’s ashes comes the Air, a phone as easy on your hands as it is on your eyes. It may be as droppable as any modern iPhone, but the double Ceramic Shield and titanium frame makes it as durable as ever.

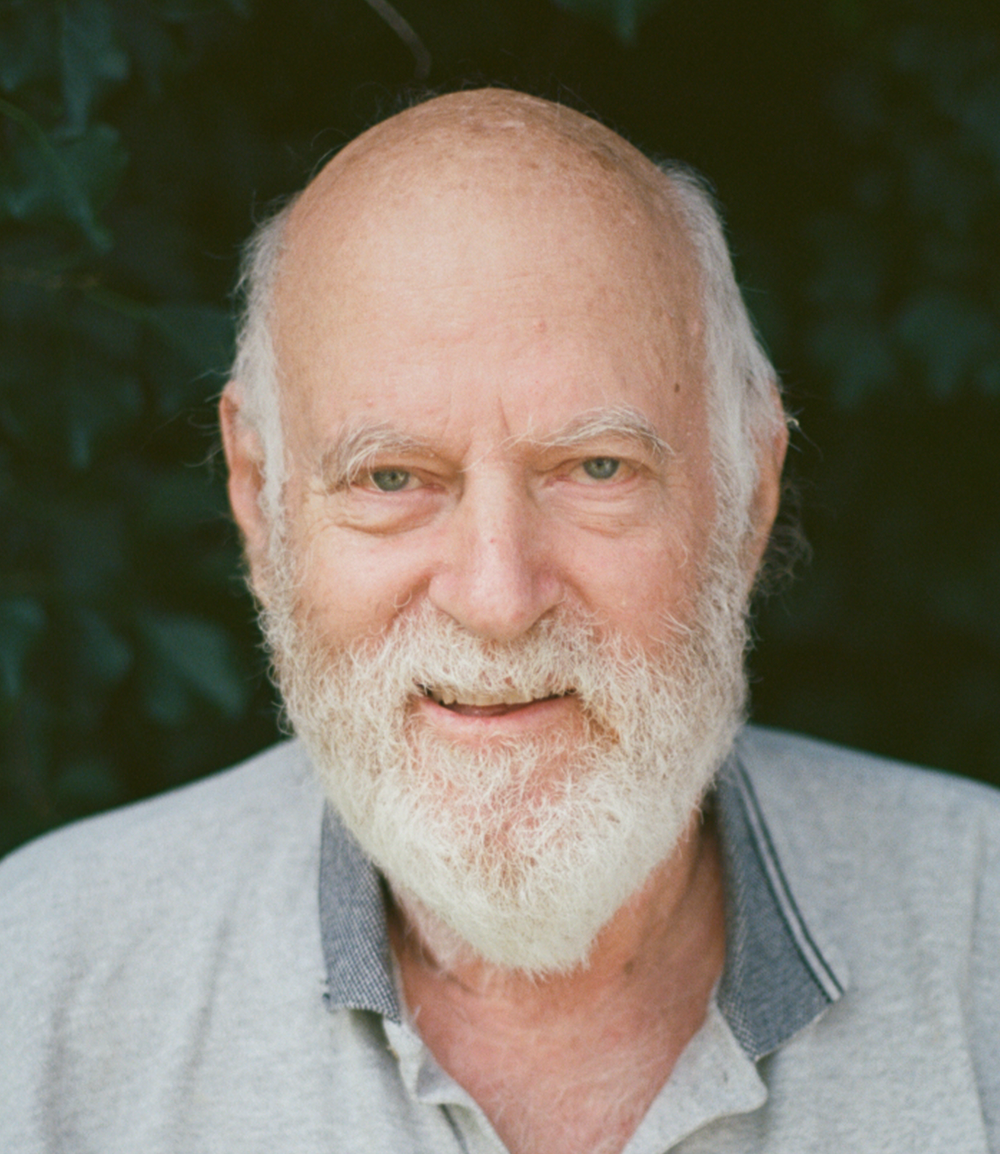

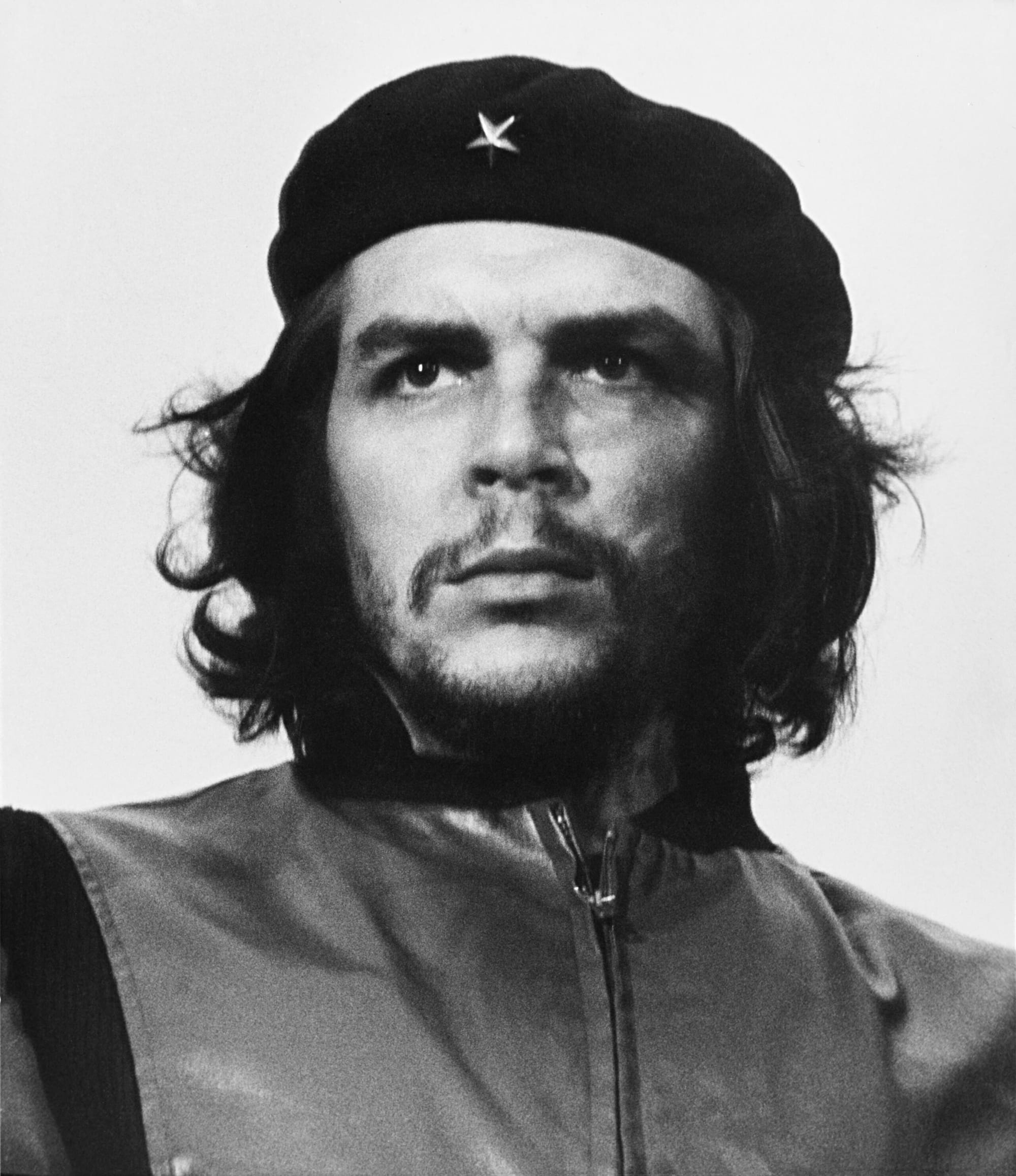

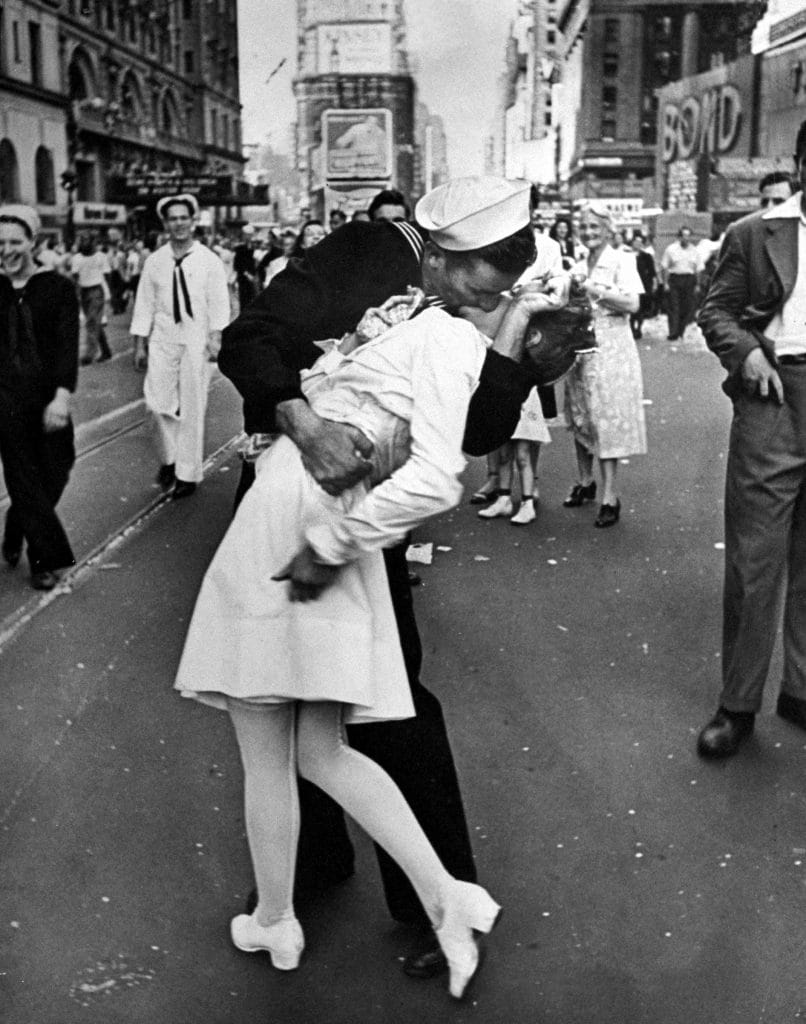

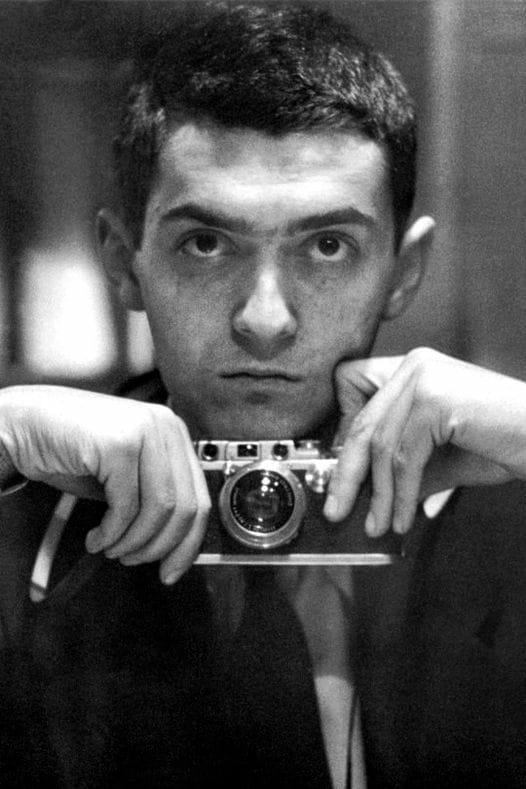

Last week I set out to write a few thousand words on the iPhone Air, but found my mind pulled in another direction, to an iconic camera design. You may not know its name, but you know its work.

Guerrillero Heroico, V-J Day in Times Square, Rising a Flag over Reichstag,

Invented by Oskar Barnack in 1913, the compact 35mm rangefinder may be the most influential camera of the 20th century.

By modern standards, early rangefinders were lesser cameras, lacking auto focus and auto exposure.

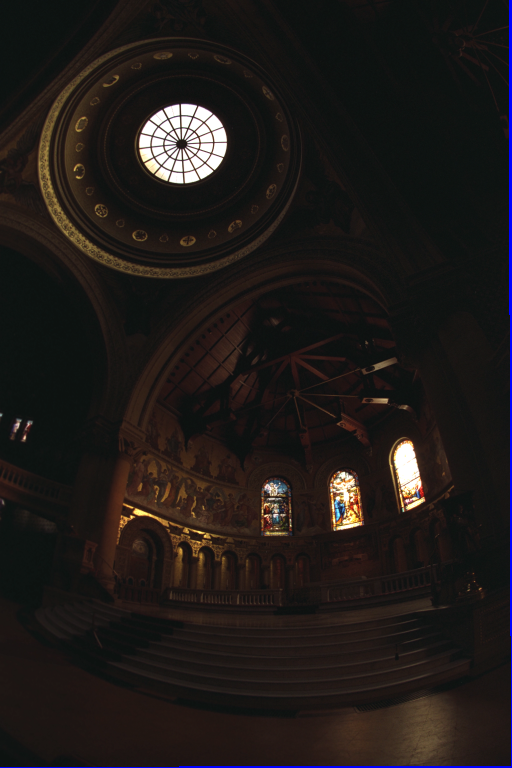

In many ways, the rangefinder is outright flawed. It’s hard to frame close shots, it doesn’t do macro, and zoom lenses don’t exist. This isn’t a camera for National Geographic. Yet thanks to its compact size, durability and stealth, the 35mm rangefinder excelled at candid portraiture, street photography and journalism.

SLR cameras addressed the flaws, winning the hearts and wallets of consumers by trading size and noise for convenience. Still, there’s something about the rangefinder that feels perfect. When compact digital cameras removed the need for film or mirrors, a decade of experimentation converged designs that resembled 35mm rangefinders, minus one important feature: taste.

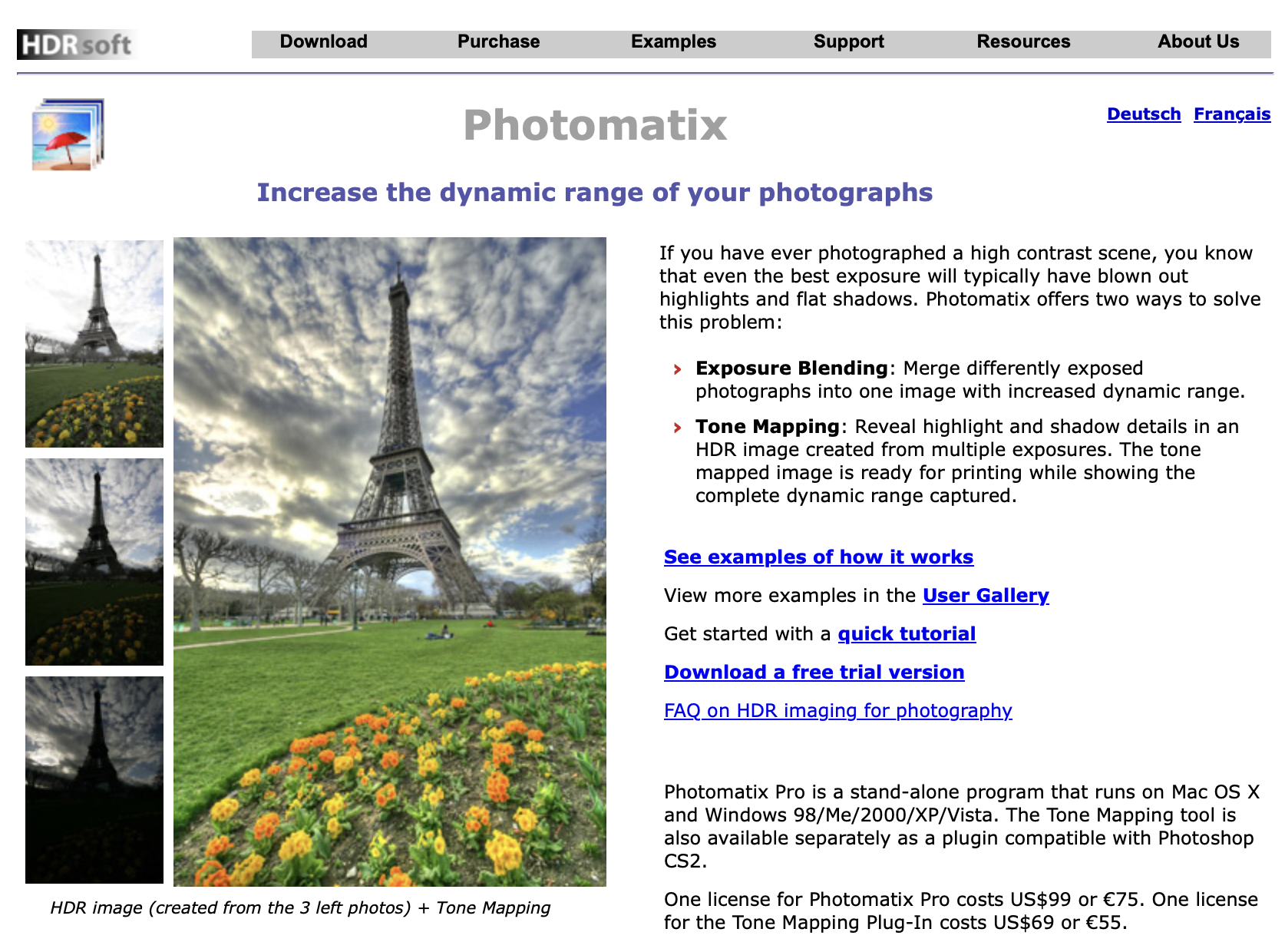

In a world of consumer electronics made of cheap plastic and garish logos, the iPod proved people would pay a premium consumer electronics with beautiful aesthetics. So in 2010, Fujifilm tried a bold experiment. They designed a camera with the conveniences of a modern point-and-shoot, a fixed 35mm lens, and wrapped it in the aesthetics of the classic rangefinders.

Their X100 should have been a swan song to a bygone era. In a few years, the point and shoot market collapsed as normal people realized smartphones were good enough. The X100 debuted at $1,199, twice the price of an unlocked iPhone 4, it proved a smash hit, defining a new camera category.

15 years later, Fujifilm just launched their high-end, $6,000 variant, the GFX100RF. The RF standing for rangefinder, but this refers to its design language, not the hardware. Today, “rangefinder style” means, “a beautiful, rugged point-and-shoot with a fixed, wide angle lens.” It’s a device that functions as both camera and fashion accessory. Does this sound familiar?

The Air distills an iPhone to its spirit. While the iPhone Pro’s bevy of lenses make it perfect for a trip to the Galapagos, the Air seems perfect for street photography, journalism, and candid portraits.

Is one lens really enough? Will you miss ProRAW and LiDAR? To put this to a test, I took to New York with an iPhone Air and an M6.

A mixture of iPhone and Film photos. Which is which? Keep reading.

The Natural Focal Lengths

Before we dig into the iPhone, let’s talk about lenses in general. Why are 50mm and 35mm the most popular focal lengths for documentary work? There’s a myth that 50mm approximates human vision. In fact, our entire field of view is technically 17mm, but visual perception is more nuanced than a single number.

Humans actually see on two levels. Our peripheral vision is very wide, but low detail. It probably evolved to spot predators out of the corner of our eye. We also have a narrow but high detail central vision, which you’re using right now to read these words. Central vision is about 43mm, which sits between 50mm and 35mm.

I’m not saying scientists met with lens makers to arrive at those numbers. Photographers probably just bought more of those lenses because they felt right. Still, it’s interesting there’s physiology to back it up.

Anyway, if you go from 35mm to 28mm, you get a little extra breathing room. It comes in handy in close quarters or wide expanses.

Of course you have to deal with more unwanted stuff in your shots.

But you can always crop to 35mm.

If you don’t know what lens you’ll need for the day, there’s a simple rule of thumb. Can you only carry one lens? Make it a 35mm. Can you carry two? Make them 50mm and 28mm.

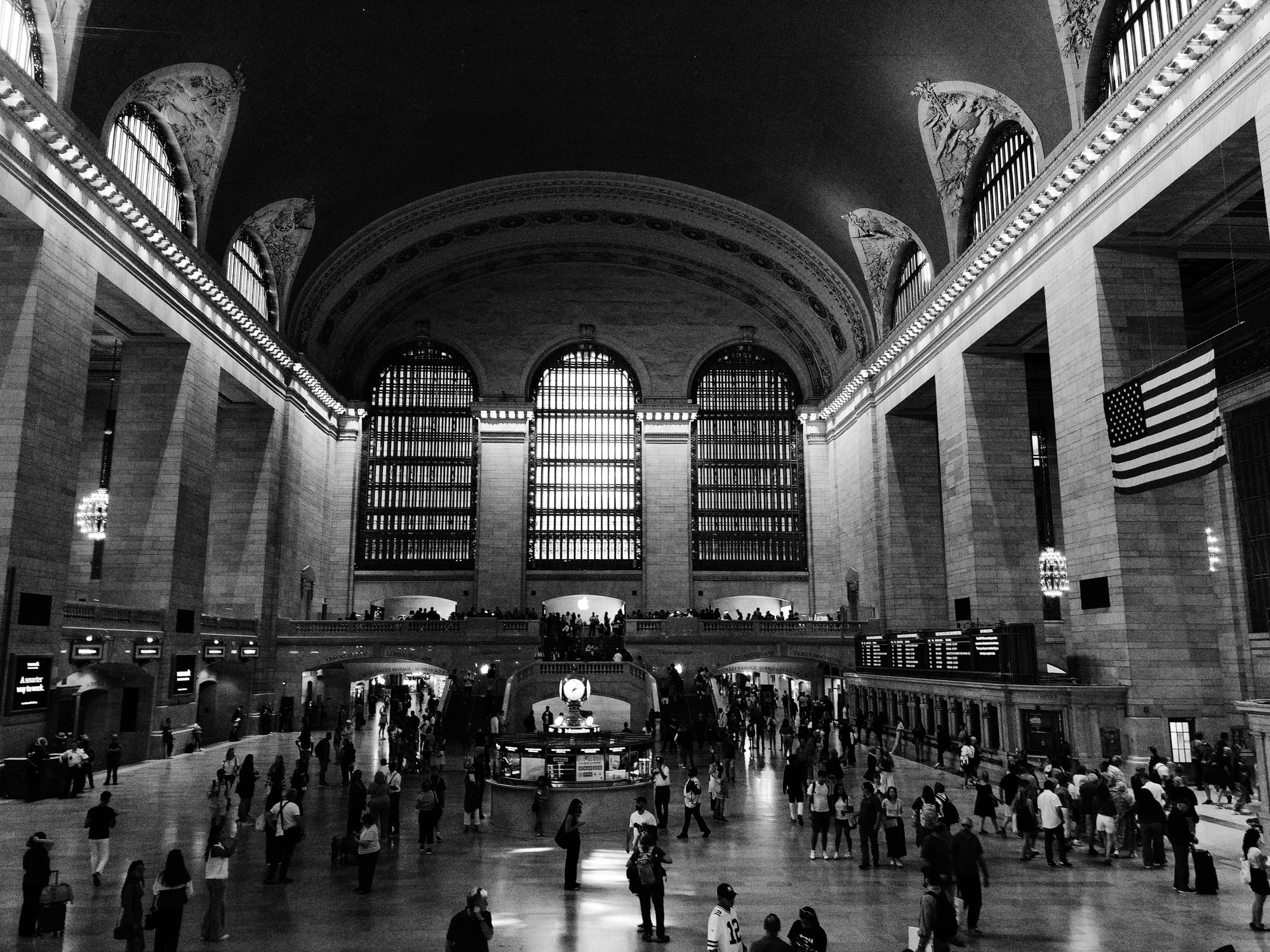

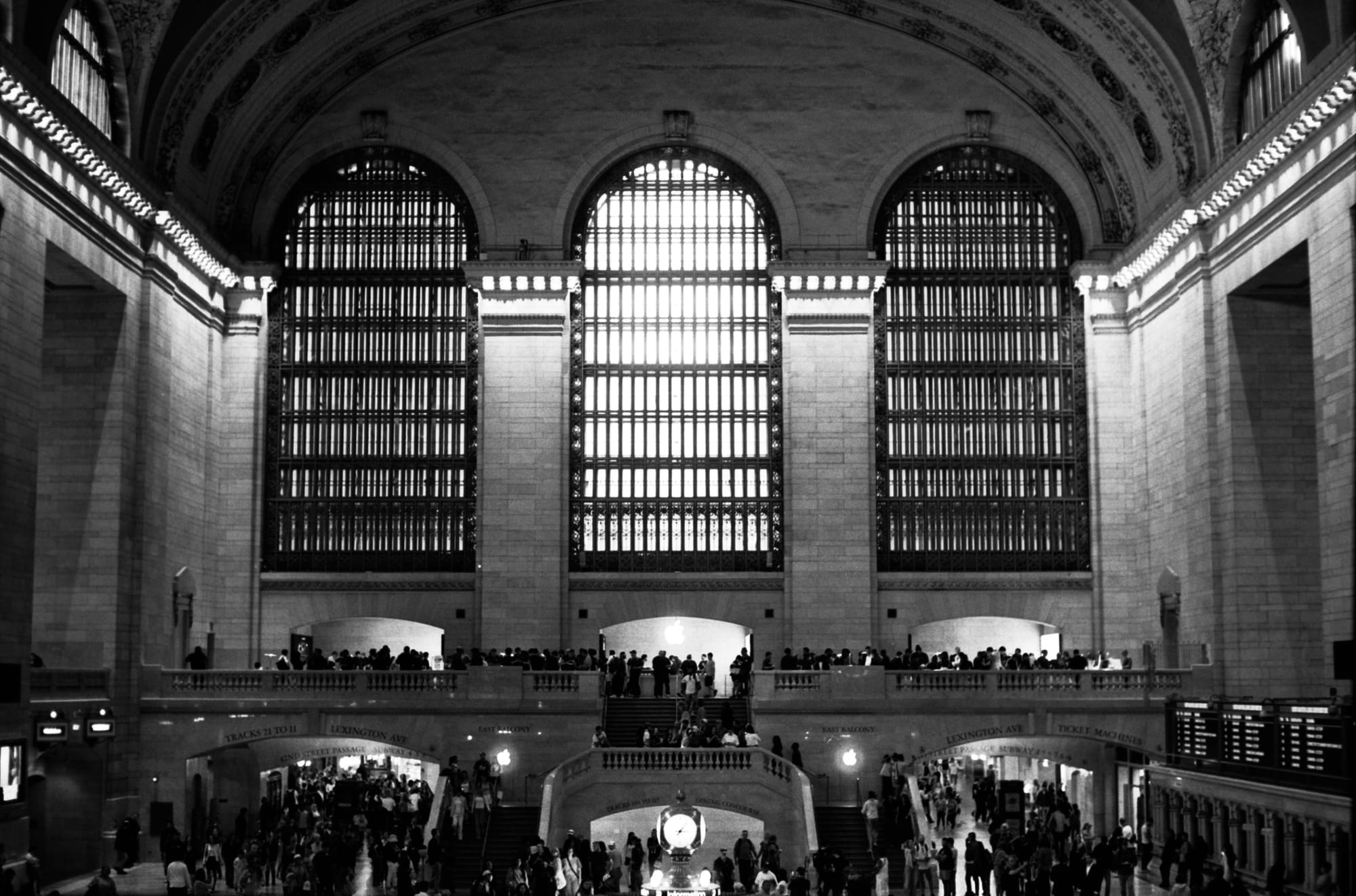

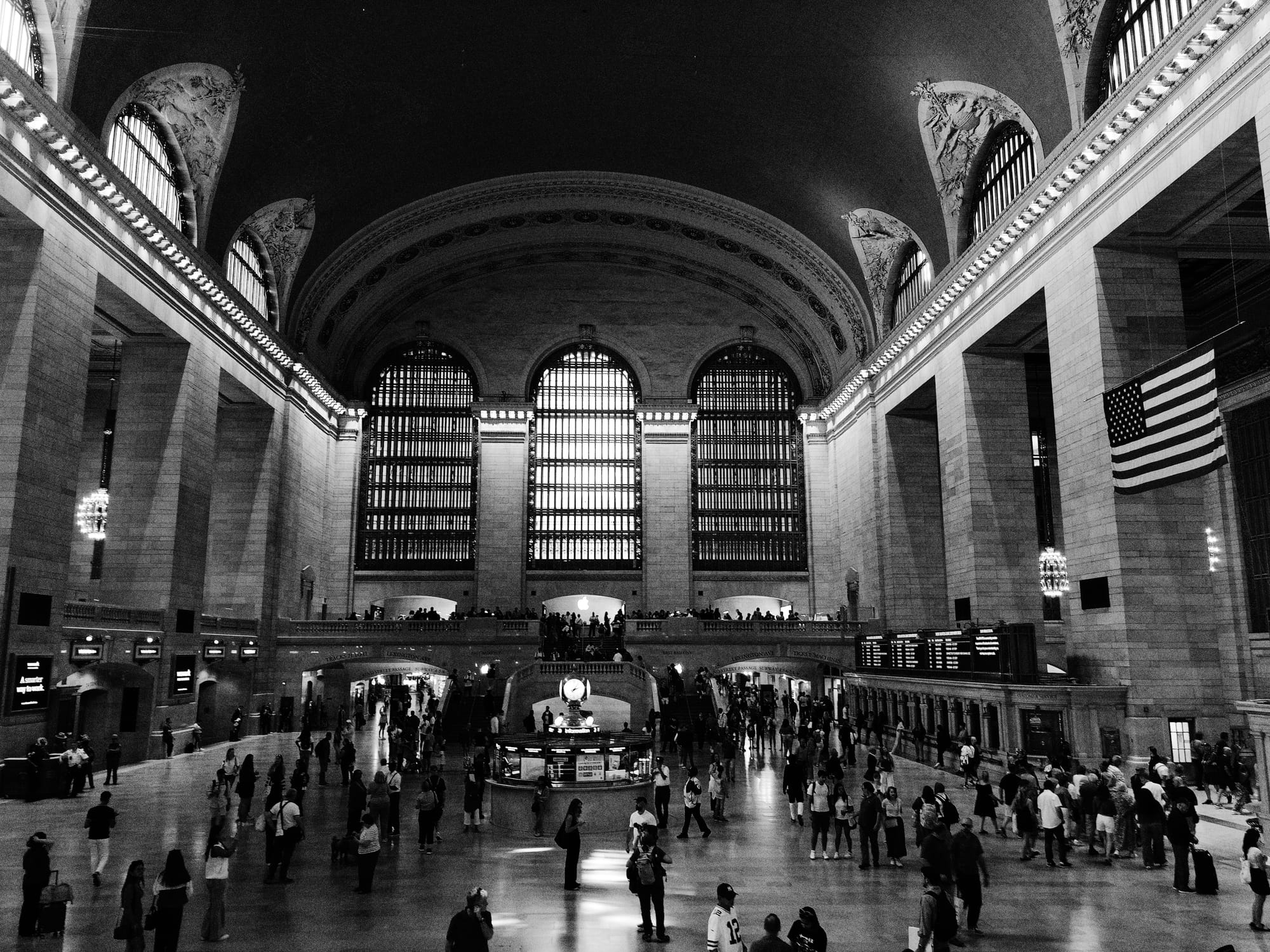

I made the mistake only packing my 50mm for my trip to Grand Central, but the 26mm on the iPhone Air came to the rescue.

50mm shot on film vs 26mm on the iPhone Air.

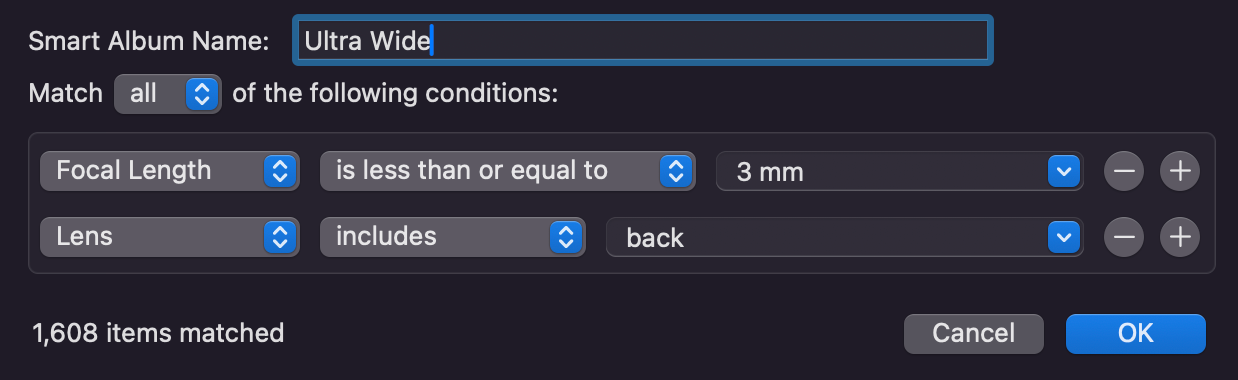

Will you miss the ultra-wide lens, a stable of almost every iPhone for the last six years? There’s an easy way to check. In the Photos app on a Mac, create a new Smart Album.

I found only three photos from the last year that make me go, “I’m glad I had that ultra-wide!” The first was the 7-mile wide Hubbard Glacier in Alaska.

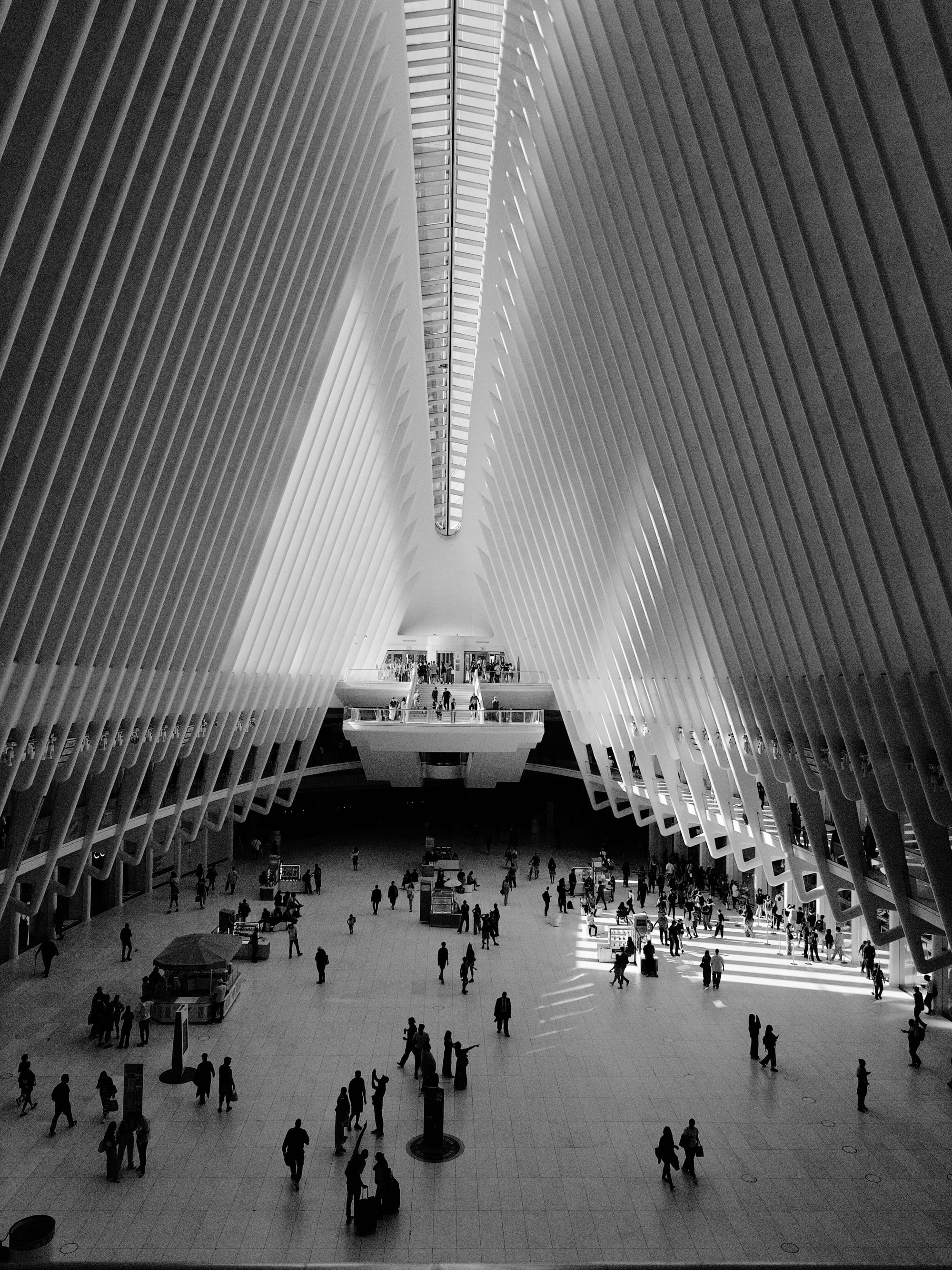

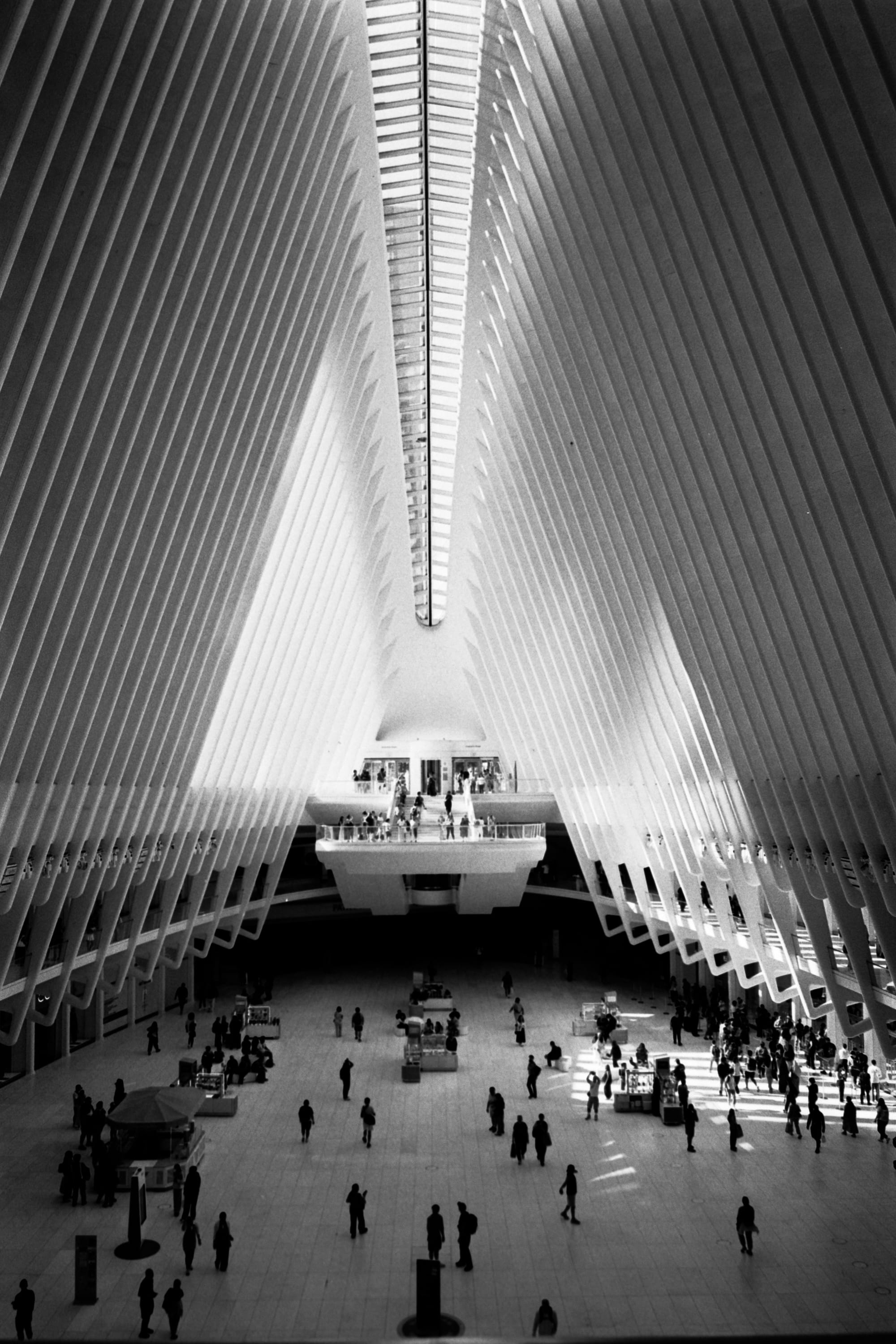

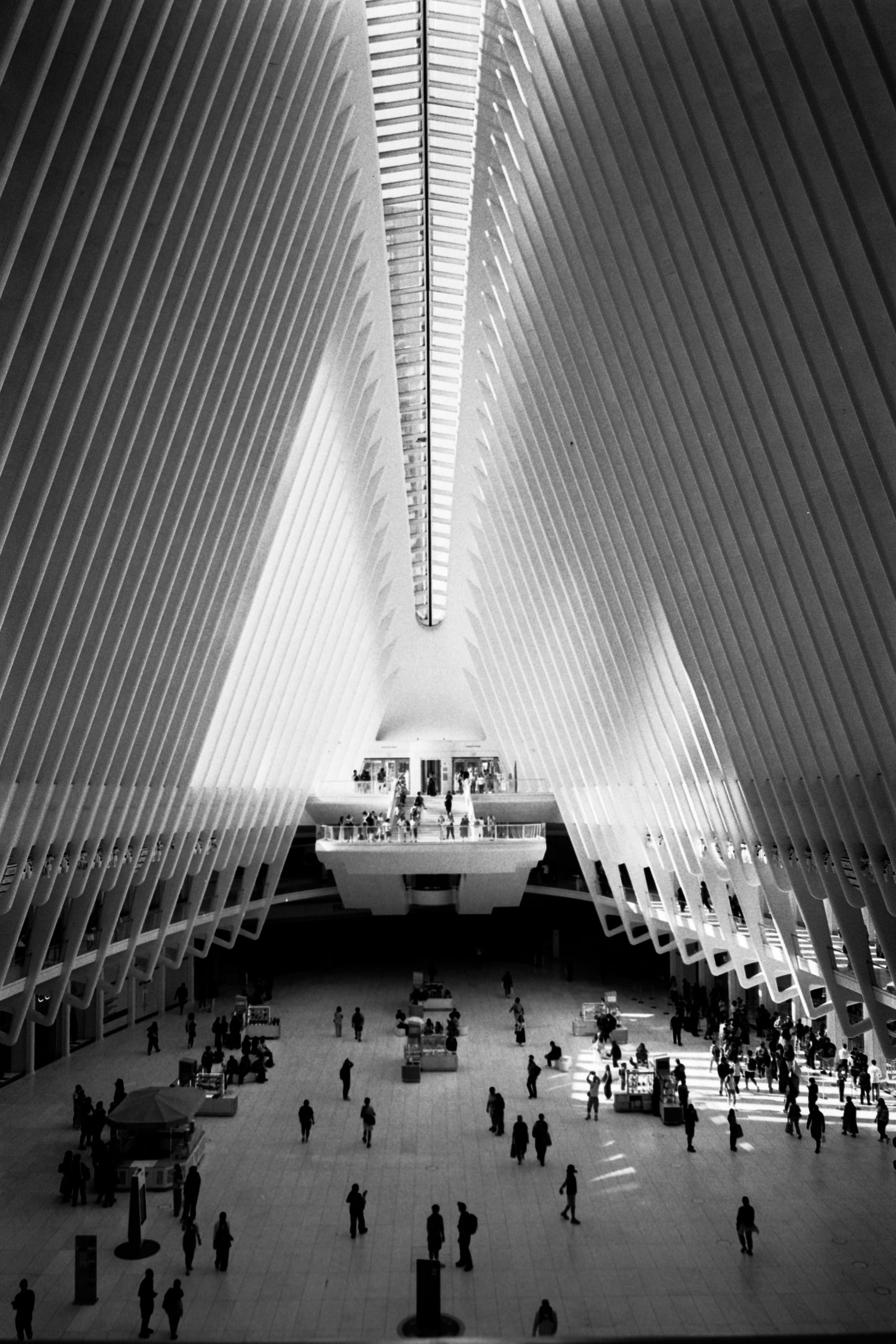

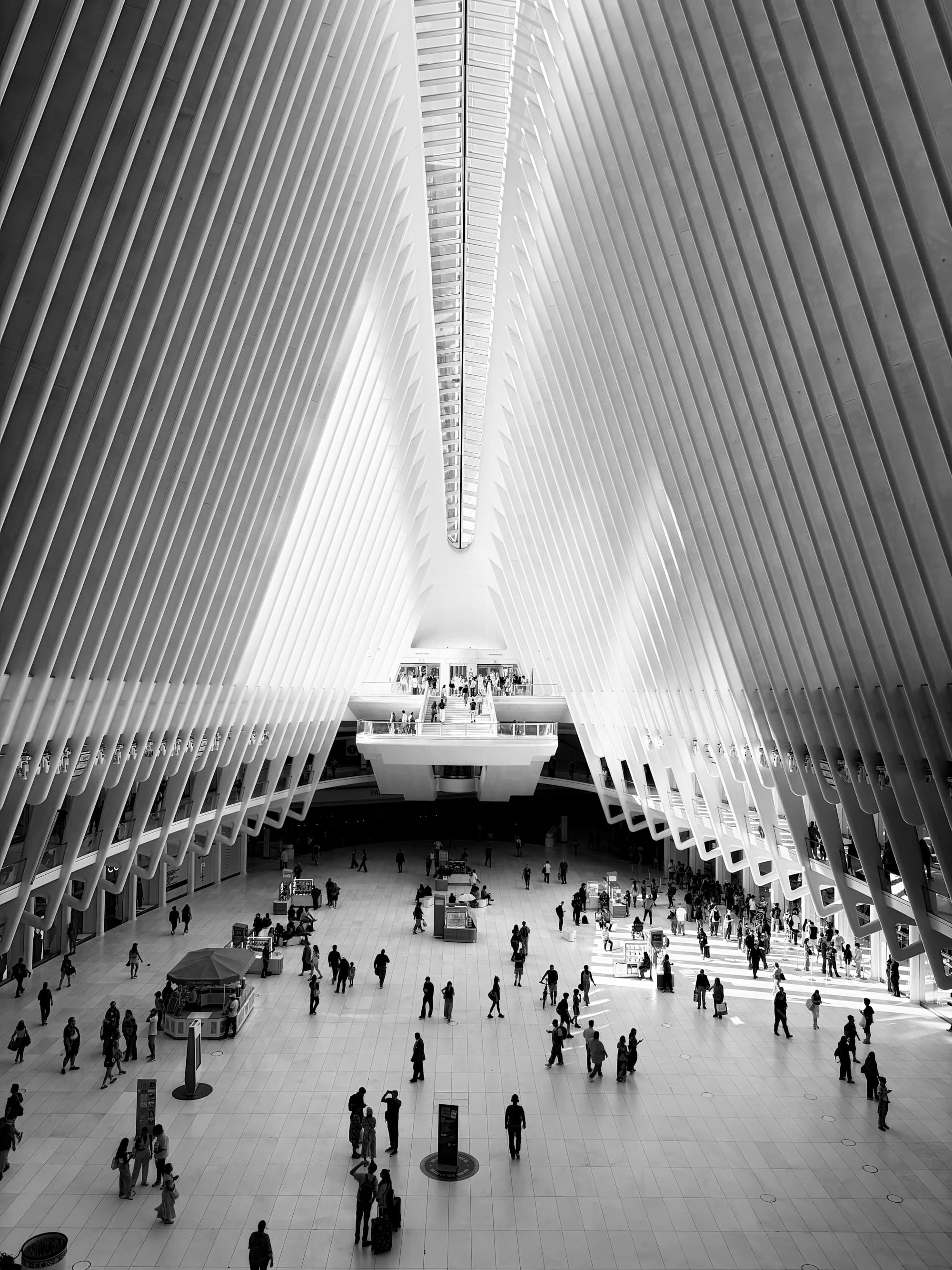

The second was the exterior of the Oculus:

The third wasn’t wide at all! Don’t forget that lens doubles as a macro.

I bet I could get away with the panorama mode in Apple’s camera, but it’s a bit disappointing to lose macro. Halide may have a macro feature that works on every iPhone, but we’re the first to warn users that software cannot match a true macro lens.

If you love bug shots, the Air is not for you. But the available focal lengths are more than enough for the rangefinder crowd.

Computational Photography and (Lack of) ProRAW

Now that we’ve gotten composition out of the way, let’s talk about image quality. By that I mean algorithms.

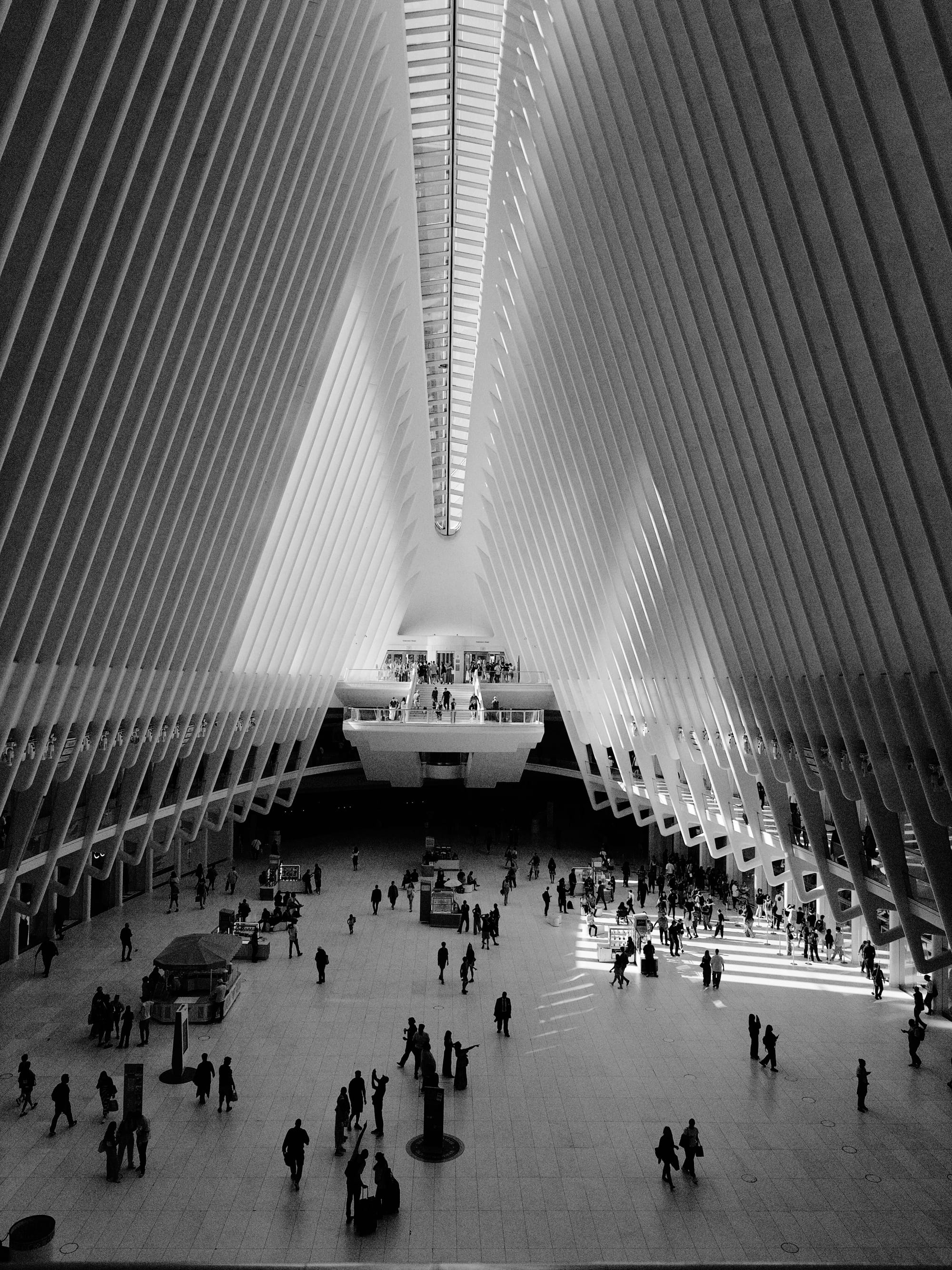

Camera algorithms are a faustian deal. Sure, they “fix” photos, raising shadows and taming highlights, but it costs you control. Compare the earlier shot of the Oculus on film to the default shot out of the first-party camera.

I know this down to taste, but after seeing the dramatic contrast of the black and white film earlier, this all-too-perfect lighting feels wrong. It makes me as uncomfortable as staring into the cold dead eyes of generative AI.

Let me get this out of the way: I am not one of those elitists who resent how the iPhone has become Gen-Z’s gateway to photography. I’m glad we’re at the point where beginners don’t need to get bogged down in technical details like film ISO and f-stops before they can get a decent photo, let alone something you’d hang on your wall.

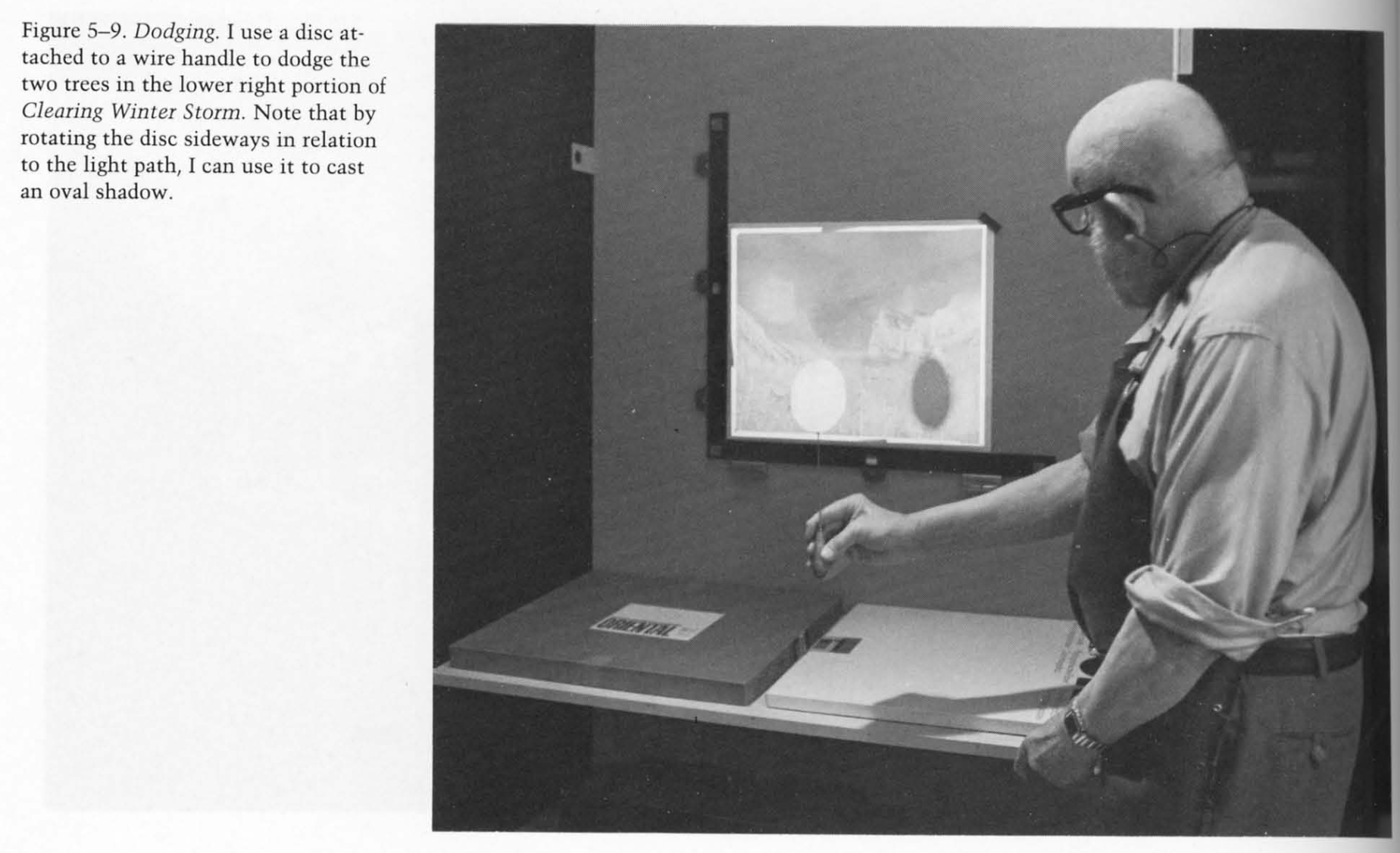

The issue is that “fixing” the lighting in photos means wrestling contrast from the hand of the photographer. Contrast is one of the photographer’s most powerful tools!

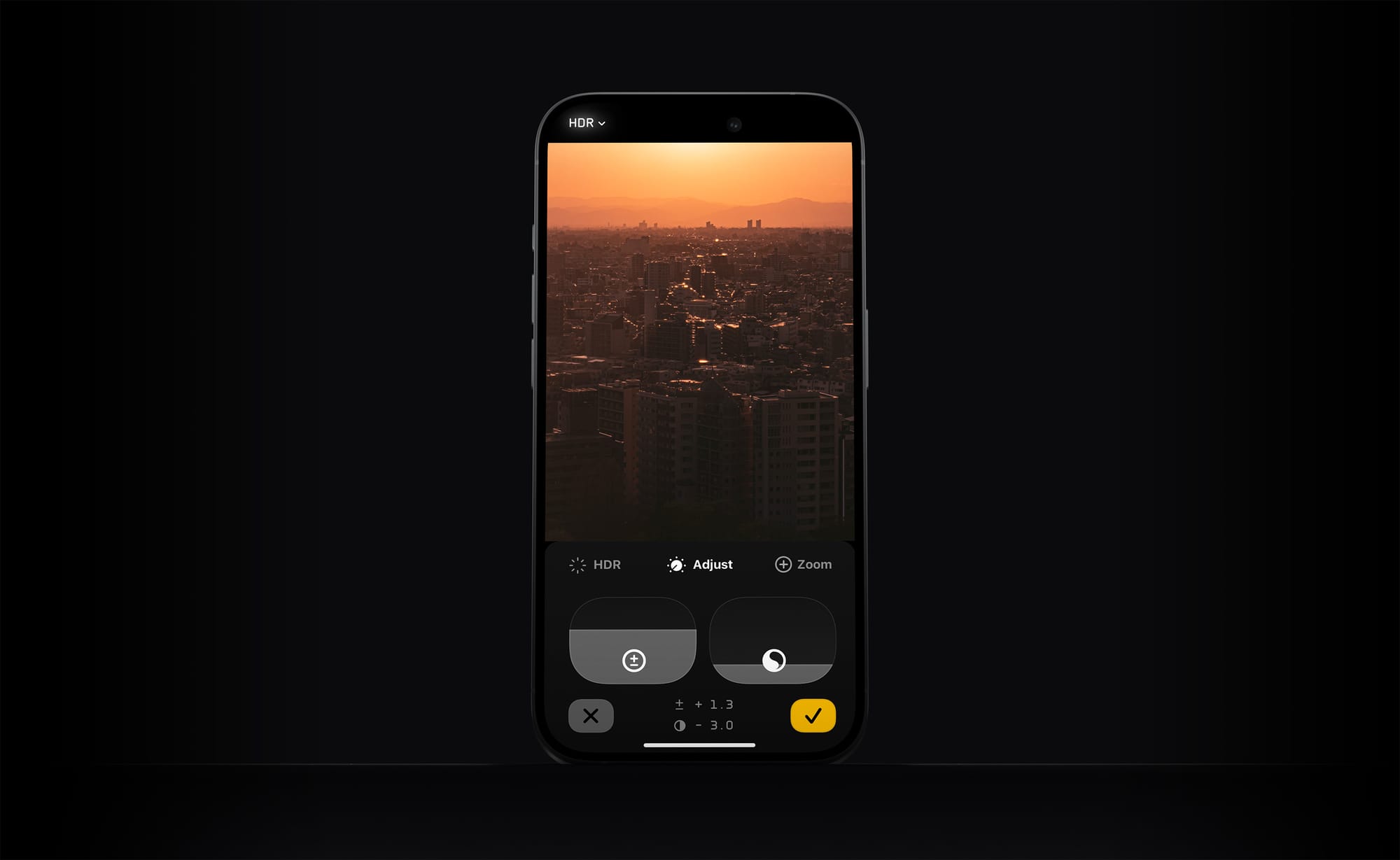

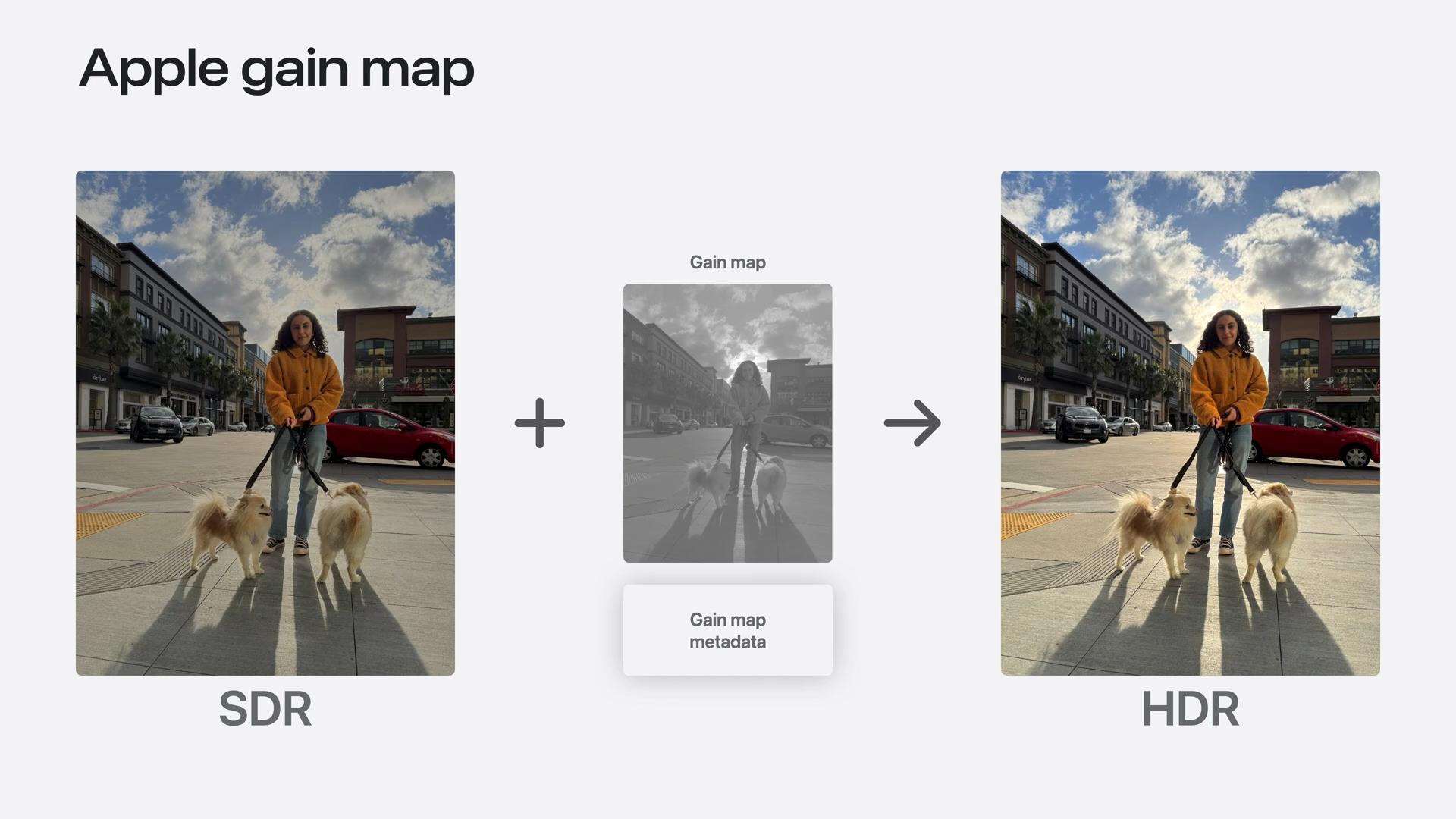

Apple addressed this in 2020 when they released the image format they call ProRAW. If you’re interested in its tradeoffs, we wrote a few thousand words about them, but in short, ProRAWS are not RAWs in the traditional sense. These a semi-baked version of their computational photography, with methods to turn down effects like tone-mapping and sharpening. That’s all moot in the case of the Air, as Apple restricts ProRAW to its Pro models.

ProRAW hasn’t changed much since its introduction in 2020. Instead, Apple has focused its resources on a new feature called “photographic styles.” In addition to color presets, you have access to a new “tone” control. Maybe you won’t get the latitude of ProRAW, but maybe we can match the film look?

Not bad, but there are two problems. One, unlike ProRAW, Apple has limited this control their Photos app. You can’t tweak tone in third party apps like Lightroom or Halide. The second problem occurs when you zoom in.

Notice a lack of texture. That’s because this photo was not generated from a single capture. My iPhone took a series of captures, and merged them together to improve dynamic range and reduce noise. There’s nothing you can do about this with Photographic Styles. Even ProRAWs have limited control over this, because noise reduction is a byproduct of Apple’s algorithms.

Whenever people accuse their phone of applying digital makeup to faces, or textured objects turning to plastic, this is what they’re talking about. When your annoying hipster friend goes on and on about “the warmth of analog,” they’re talking about film grain, the extra texture caused by the random activation of silver halides as light strikes emulsion.

Digital cameras may act different than film, but many people (myself included) find that the noise from a digital camera sensor adds an organic quality. The good news is that back by capturing a traditional, Bayer (a.k.a. “Native” a.k.a. “Real”) RAW. Every iPhone since the iPhone 6S supports Bayer RAW capture.

Thanks to the binning on the 48 MP quad-bayer sensor, the noise is soft and subtle. Maybe too subtle! We’ve gotten requests on our Discord for more texture, so I whipped up synthetic grain.

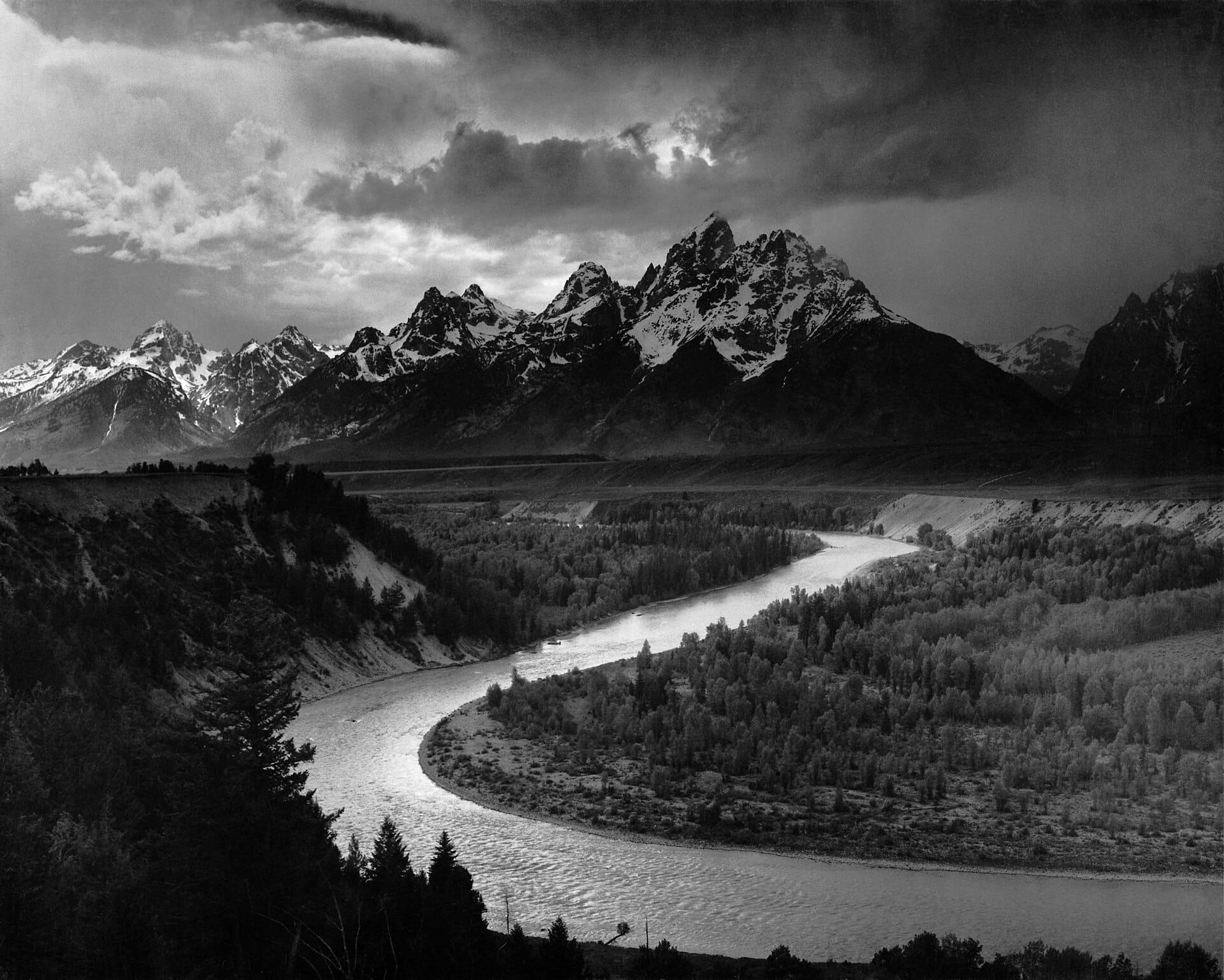

Anyway, let’s compare film, photographic styles, and Bayer RAW.

M6, Photographic Styles, and Halide Mark III

One thing you’ll miss about ProRAW is editing latitude. When shooting high dynamic range scenes, you can bring out details in the shadows that you don’t even know exist. Bayer RAWs can push and pull exposure a few stops, but it can’t work the miracles. For many people, that’s a serious drawback. For me? It makes things more fun.

Like every mid-century camera, classic rangefinders lacked auto focus and auto exposure, forcing you to think through every shot. They were technically obsolete by the 1970s, with SLRs like the Canon AE-1 tackled automatic exposure. By 1980s, we had auto focus.

Yet the fully manual nature of classic rangefinders still captivates camera nerds 40 years later. There’s just something about knowing that you, not the machine, took the photo. If you feel the same way, the lack of ProRAW makes the Air more of a camera-camera than the iPhone Pro.

A Camera for the Present Moment

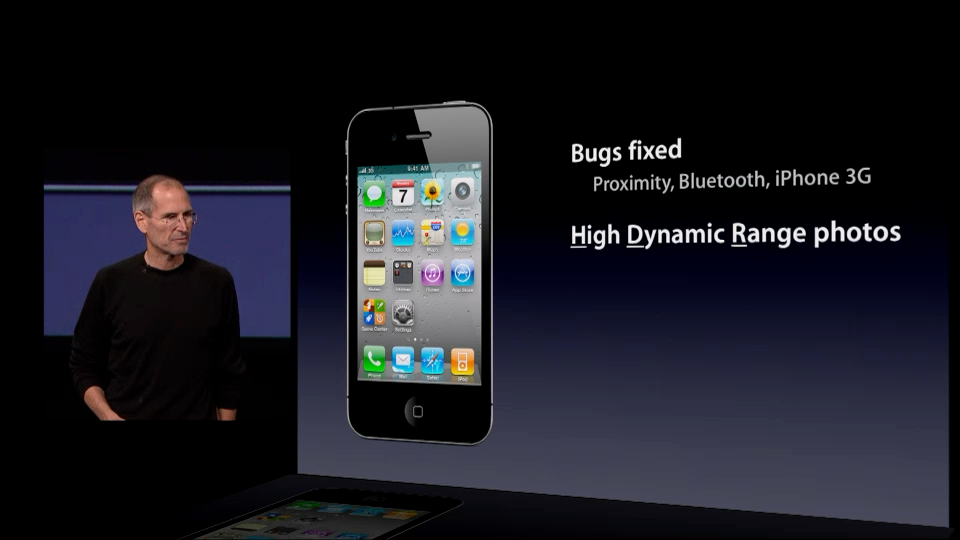

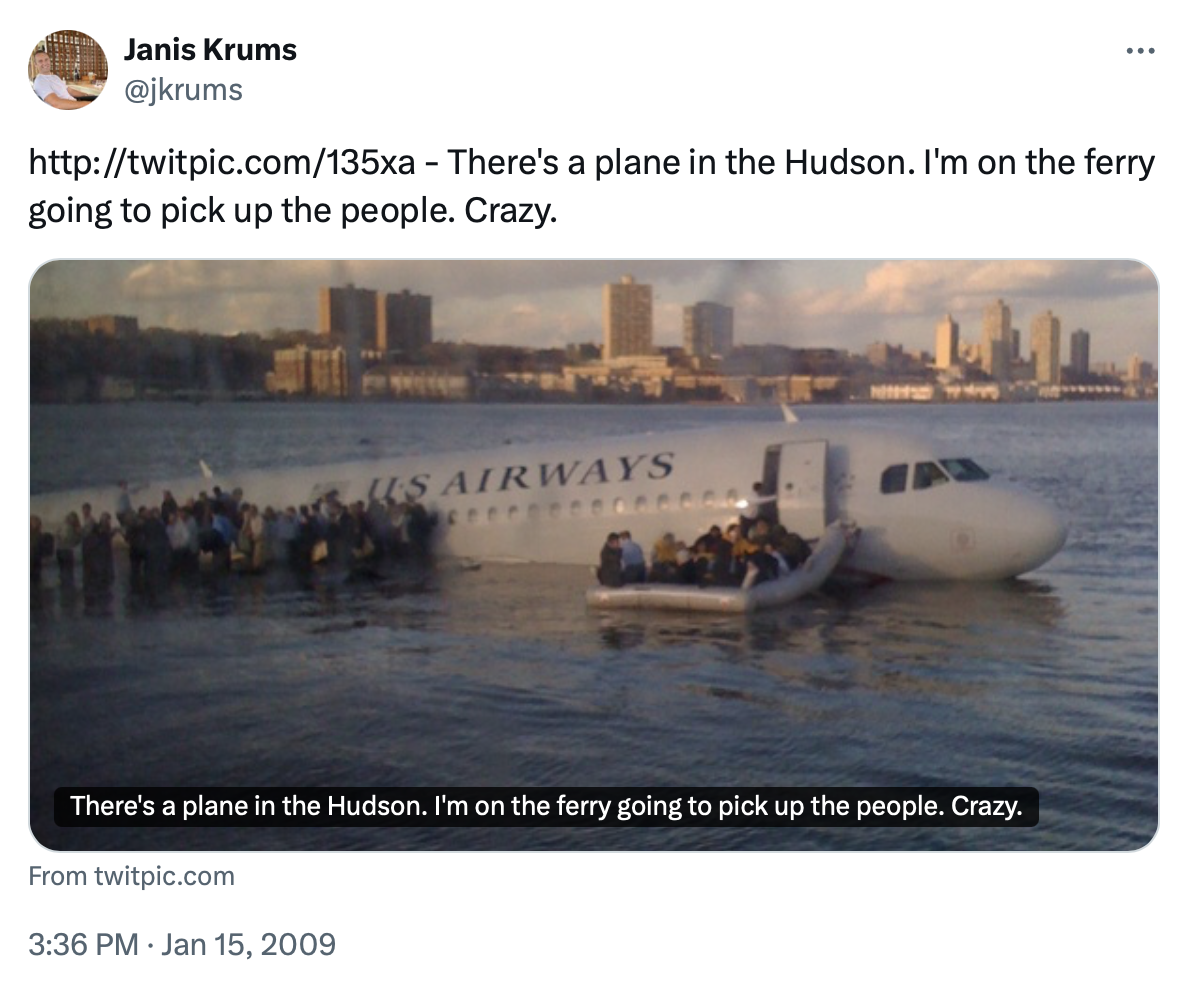

If I could pinpoint the moment the iPhone became the definitive camera for breaking news, it was January 15, 2009.

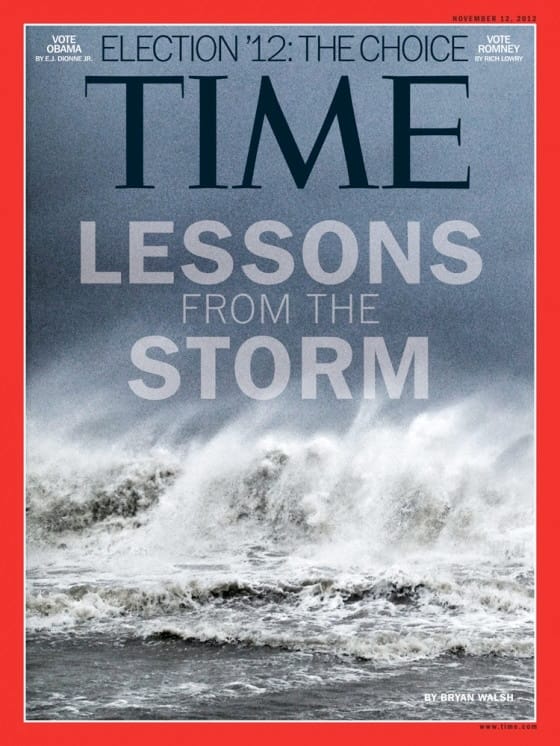

By 2012, you’d see iPhone 4S photos on the cover of Time Magazine.

The iPhone is so important for capturing once-in-a-lifetime moments that every iPhone now ships with a dedicated capture button. But how do we test an iPhone’s ability to capture history?

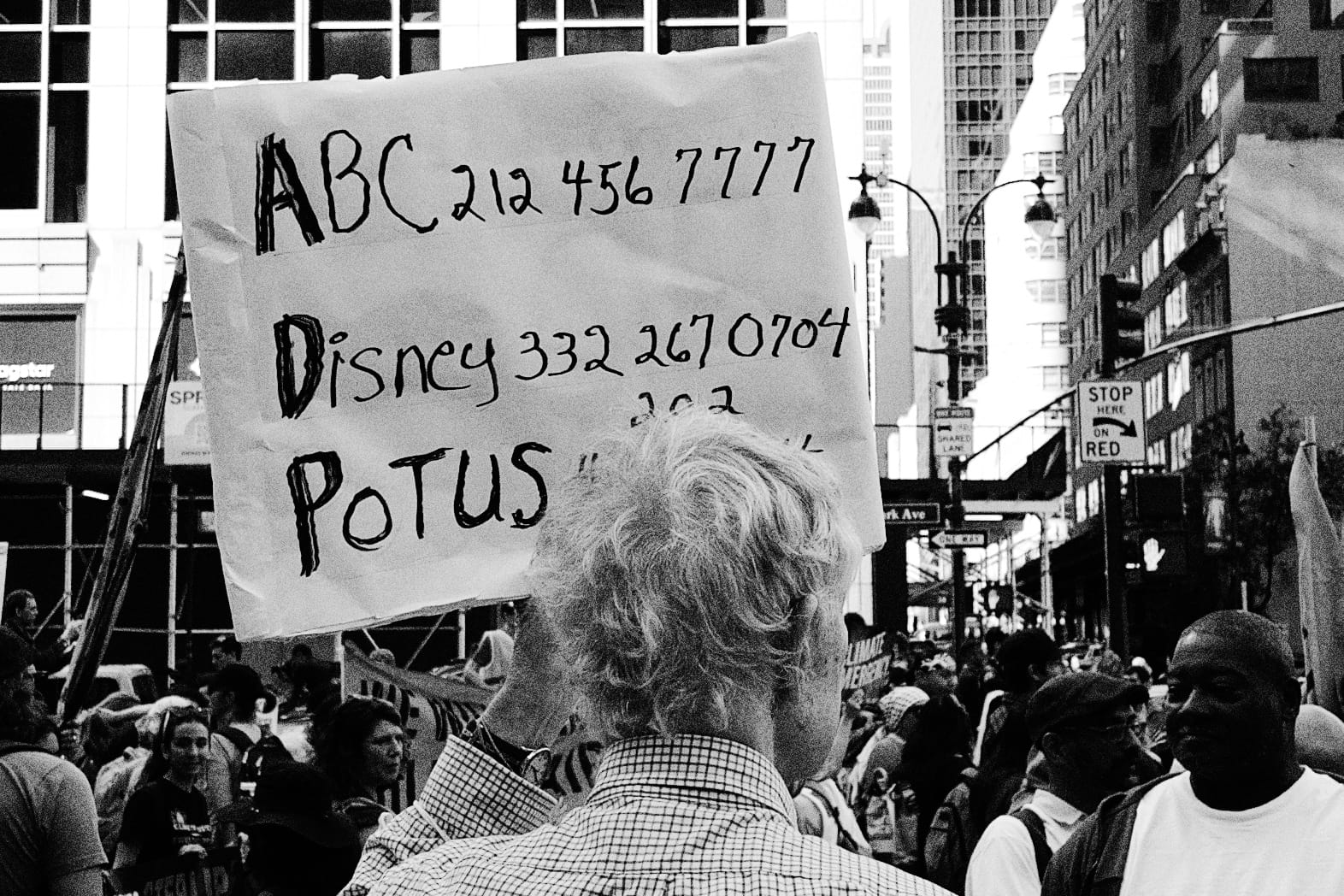

Luckily, I live in a crumbling empire. Shortly before I started this review, America’s mad king assaulted the first amendment.

Film, iPhone

One hundred years later, black and white remains the best look for a nation’s spiral into fascism.

This march didn’t start as a protest for Jimmy Kimmel. Officially, this was the Make Billionaires Pay March, a protest against climate abuse by billionaires. One highlight were the paper mache effigies of Elon and Bezos.

Film

iPhone Air

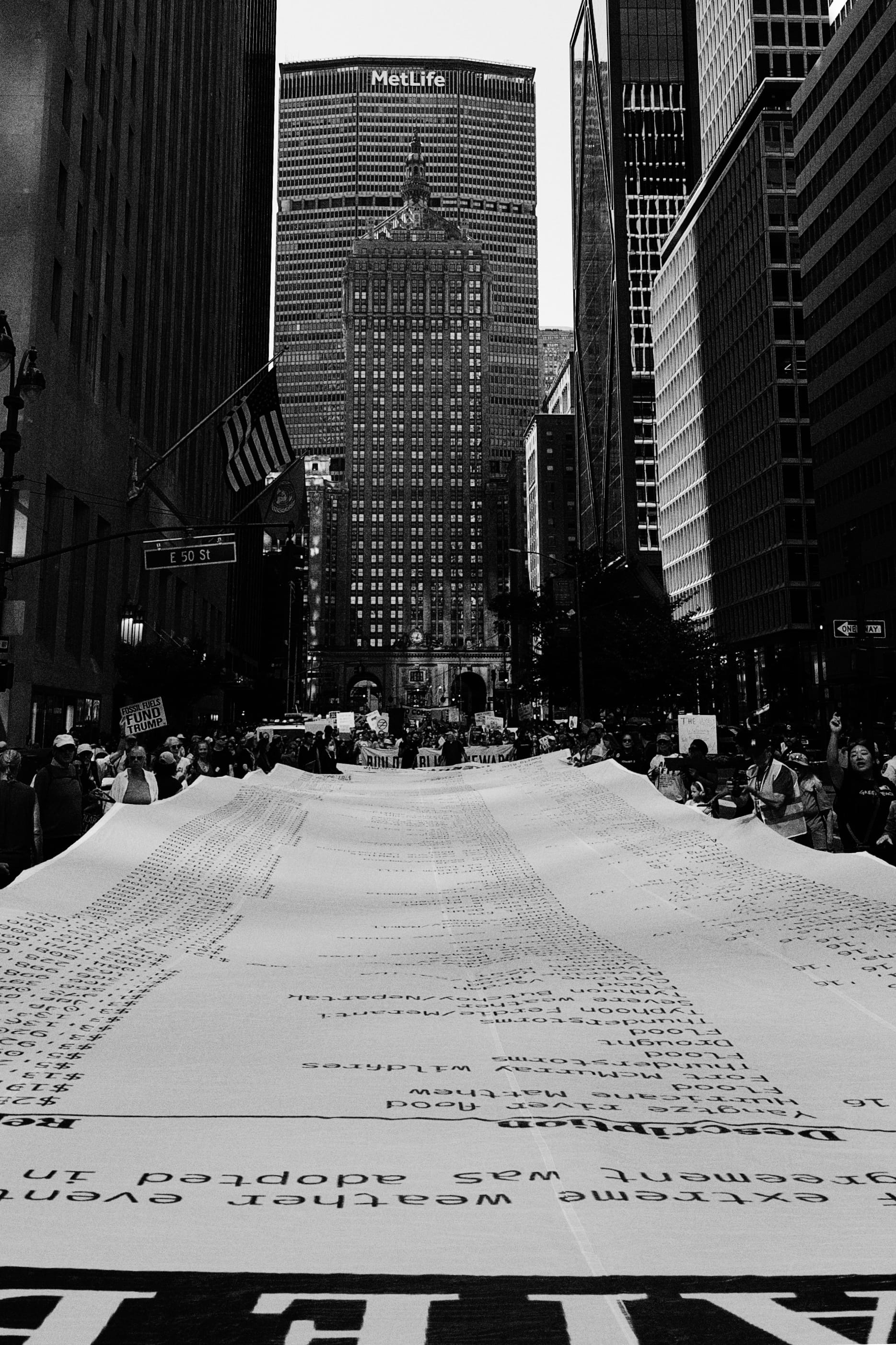

The centerpiece of the march was the 160 foot long Climate Polluter’s Bill, detailing $5 trillion of damage caused by climate change in the last ten years.

Film and iPhone

I think the reason the rangefinder captured so many great candid moments came down to its humble presentation. It didn’t scream “Camera!” like its contemporaries.

Today, seeing someone with any sort of dedicated camera draws attention to itself. In the past this might have worked to a reporter’s attention, but today feels like a target.

If our country continues its descent into authoritarianism, the most important feature of our cameras will be security. At the moment, the iPhone is the most secure camera in the world. At the moment, you can download third-party apps like Signal for anonymous, end-to-end encryption. How long will this last? As long as we keep talking about it.

Film Intermission

The Lost Art of Building Things That Last

If I treat my decades-old cameras right, they’ll last decades more. They never beg for software updates. I never wake up one morning to find the dials changed size and shape. It makes me happy thinking of a world before software.

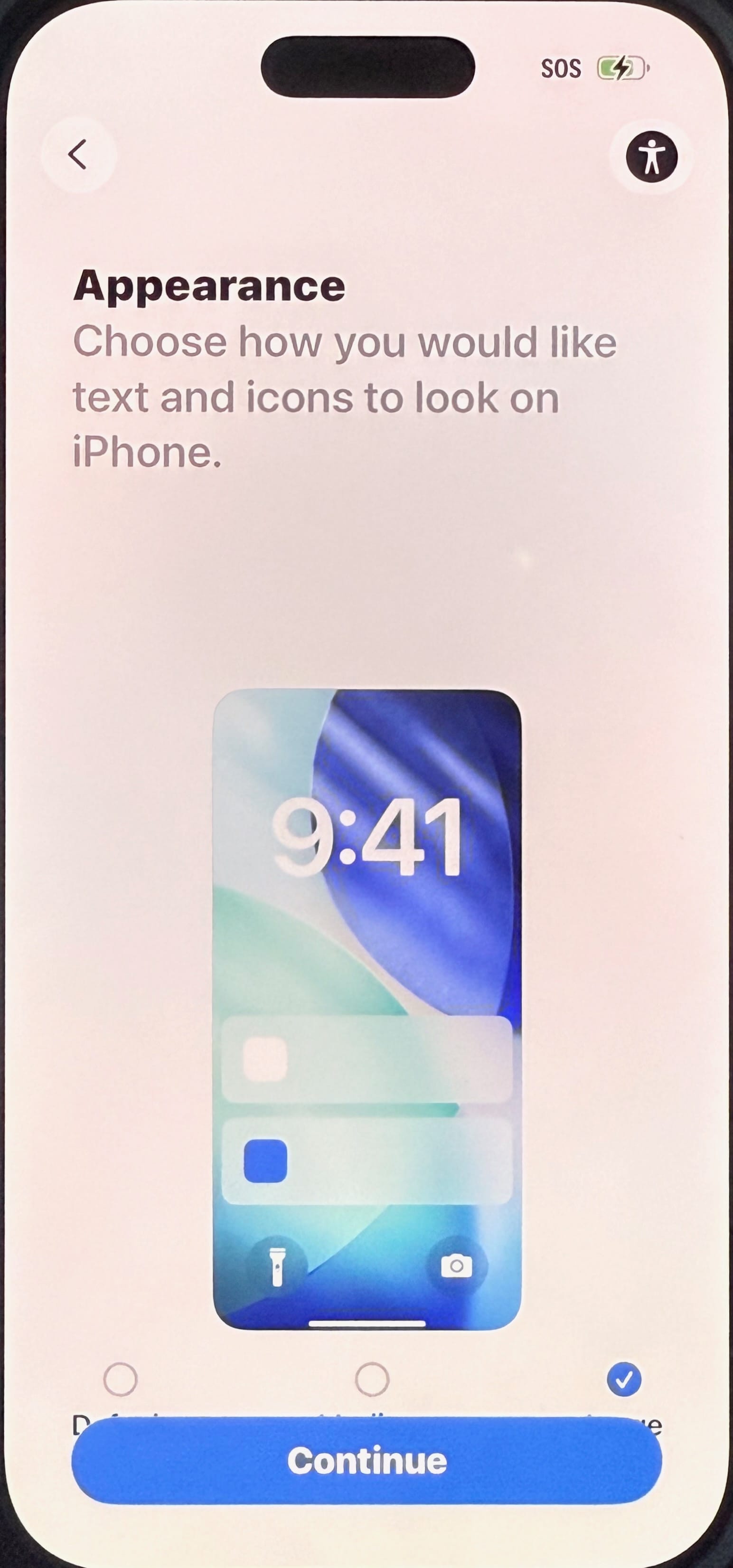

Yes, I’m a developer, and I can’t look away from the version of iOS that shipped on these phones. To be clear, I’m not talking about aesthetics.

I don’t think the problem rests on their designers or engineers. These small bugs seem like the same mistakes I’ve made myself countless times. Whenever they’ve slip into a release, it’s generally because I ran out of time to find and fix them.

It feels like Apple rushed things out the door to make a Fall 2025 release. With another year of work— maybe just another few months— this could have been a smash hit. Instead we read stories about battery drain, accessibility, and other unforced errors.

It’s just a bit ironic that if you hold off on upgrading your iPhone, you can wait to upgrade iOS until the bugs get worked out. The people who will have the worst experience paid $1,000 at launch for a device running a beta OS.

Whatever Happened to Leitz Camera?

The M6, launched in 1984, is widely regarded as Leica at its peak. It added a light meter for convenience, but if you don’t like it, just remove the battery. The camera remained fully functional without power.

In 2002, Leica launched the M7, their first model with semi-automatic exposure. It drew backlash for adding electronics, which left you with limited control if the battery dies. They responded with the Leica MP (“Mechanical Perfection”) in 2003, which dropped the electronics and basically backtracked to the M6.

Leica was in a bad position. While the rest of the camera industry transitioned from film to digital, Leica was stuck serving a niche fan base of analog purists. Their first consumer digital camera was nothing more than a reskinned Fujifilm point-and-shoot. They later partnered with Panasonic for compact Leica Digilux 1 point-and-shoot, which failed to pay the bills.

By 2004, Leica was the verge of financial collapse. It was saved by Andreas Kaufmann, heir to a 1.5 billion euro inheritance from his aunt. Kaufmann bought a major stake in the company and set out to return them to profitability. Two years later, they launched their first digital rangefinder, the infamous M8. The infrared filter on the sensor failed to do its job, causing ugly IR interference, a problem mitigated by recalls.

Meanwhile, the company juiced revenue by slapping its logo on everything from Panasonic point-and-shoots to Fujifilm instant cameras, and now Android phones and silly iPhone accessories. I guess the real money is in merchandising.

Let’s be honest, Leica was a status symbol long before its pivot into pure-brand. While war photographers went with Contax, artists took to Leica.

Even if the classic M was more status symbol than tool, at least the engineering justified its price tag. Every device felt like a work of art, hand assembled in their factory in Wetzler. Today, they crank out many products on Chinese assembly lines, if you couldn’t tell by the price hikes due to tariffs.

Leica’s optics used to be unparalleled, but today’s Voigtländer glass is ever just as good for a fraction of the price. In fact, every film photo in this post shot at 28mm was shot with a Voigtländer.

Influencers aside, I don’t know any working photographers shooting on Leica digital cameras. That doesn’t seem to worry the company. In their own words, they make “jewelry.”

Today, 55% of Leica continues to be owned by Kaufmann’s investment firm, and the other 45% is owned by the Blackstone private equity group. Maybe the company will continue to print money for decades to come, like Hermes and De Beers. Or maybe brand saturation will make it lose its cool, like Supreme.

Regardless, the Leitz Camera where Oskar Barnack invented the 35mm camera 112 years ago, is dead.

Leica earned its reputation from stellar engineering. Precise, hand assembled cameras require a high price, which accidentally made them a status symbol. It also put them in a precarious position as technology marched on.

Apple’s greatest strength in the new millennium was its lack of nostalgia or reverence. Had another company invented such iconic products as the iMac or iPod, they would have milked those designs for decades— I remember rumors that the first iPhone would feature a click wheel! Yet time and again, Apple has discontinued successful products years before they outstay their welcome, so they can make room for the next big thing.

Apple’s engineering and taste earned it a spot alongside Leica or Porsche, but this proved both a blessing and distraction. They tried to get into high fashion with a $10,000 solid gold Apple Watch, and it flopped because they went about things backwards. At launch, Apple didn’t fully understand why the Apple Watch should exist, and they hid that with marketing until customers told them, “This is for fitness.” It’s ironic that if they hadn’t shot their shot at launch, I bet they could release a gold Apple Watch today.

Apple is known for beautiful, well engineered products, and I worry they damaged that reputation to hit an arbitrary deadline. I worry about Apple losing its sense of taste, as they send tacky push notifications to our Wallets to promote a movie, and sacrifice valuable screen real estate to promote paid services.

Apple still makes the best products in world, and I still buy them, but I hope someone in Cupertino is minding this course. Their biggest threat isn’t an Android as good the iPhone, any more than Per Se should worry about Gray’s Papaya. The only threat to Apple is Apple.

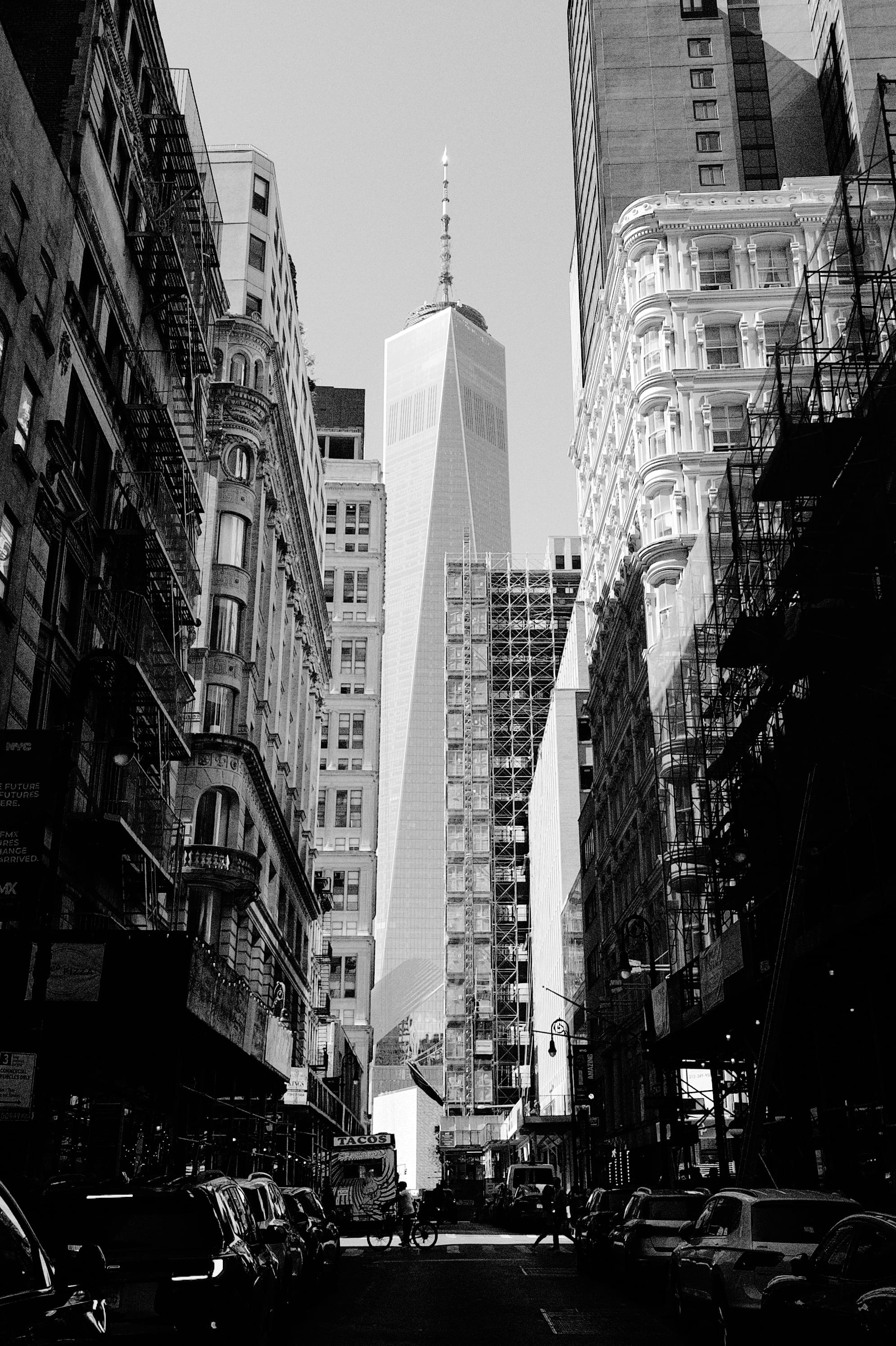

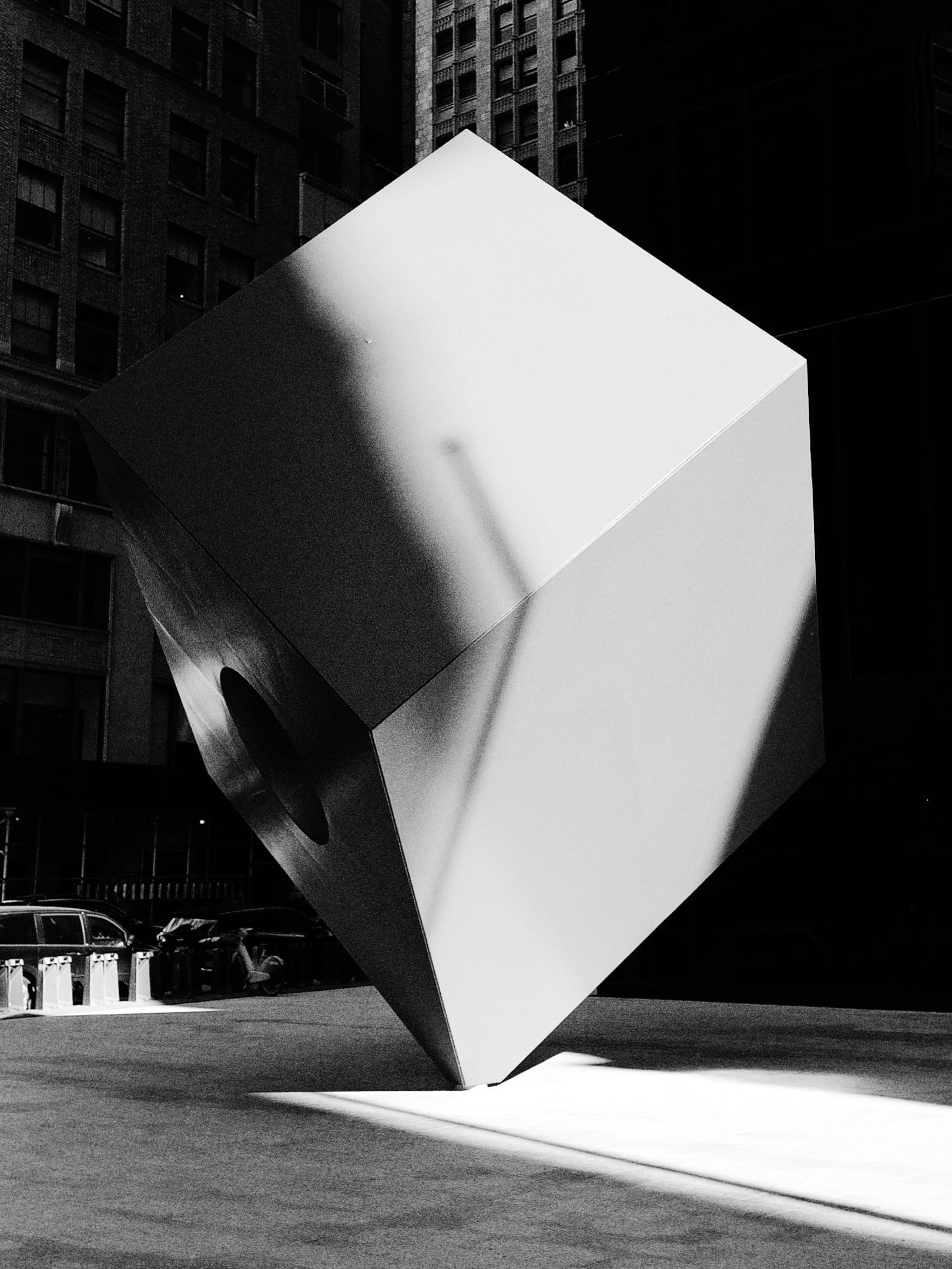

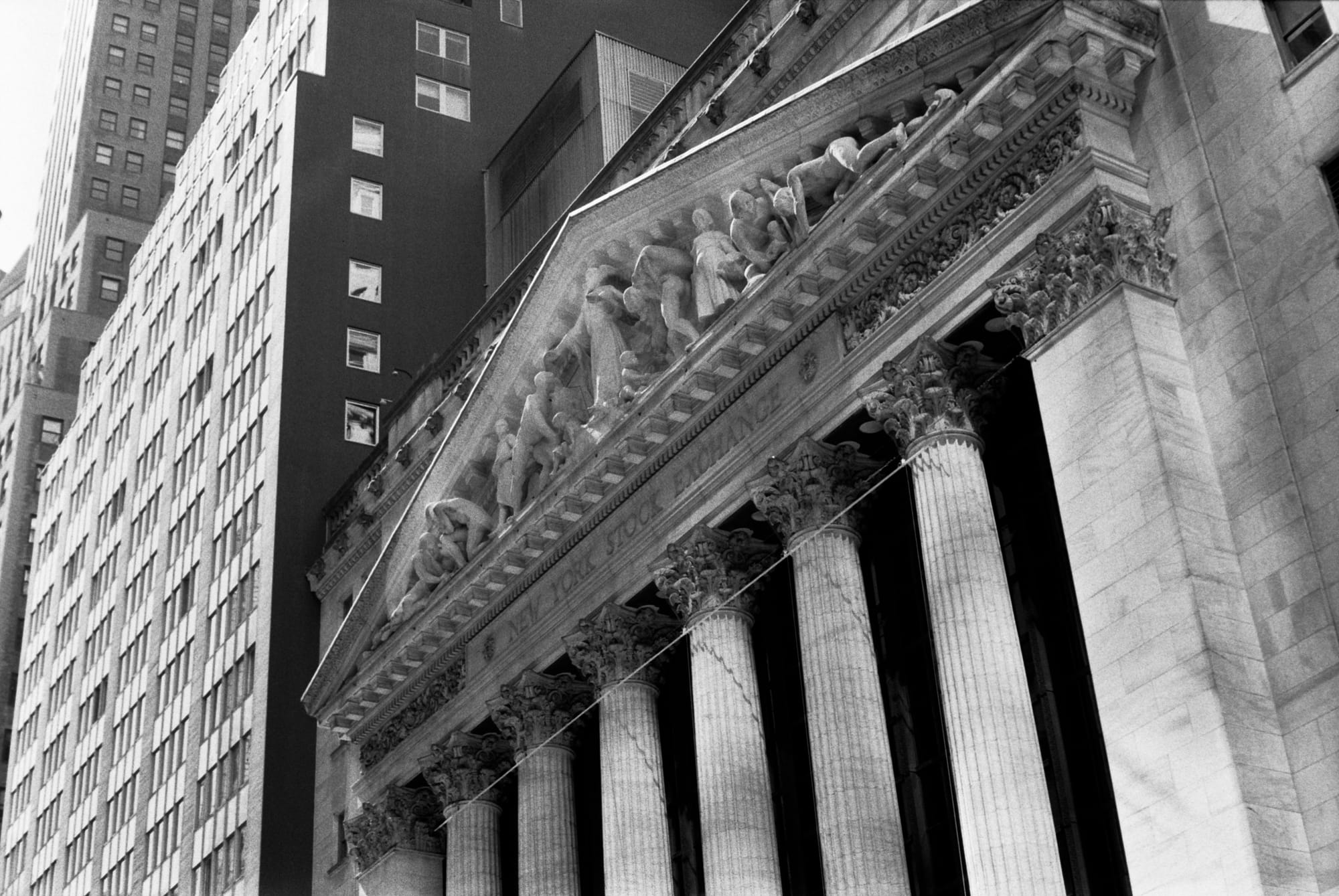

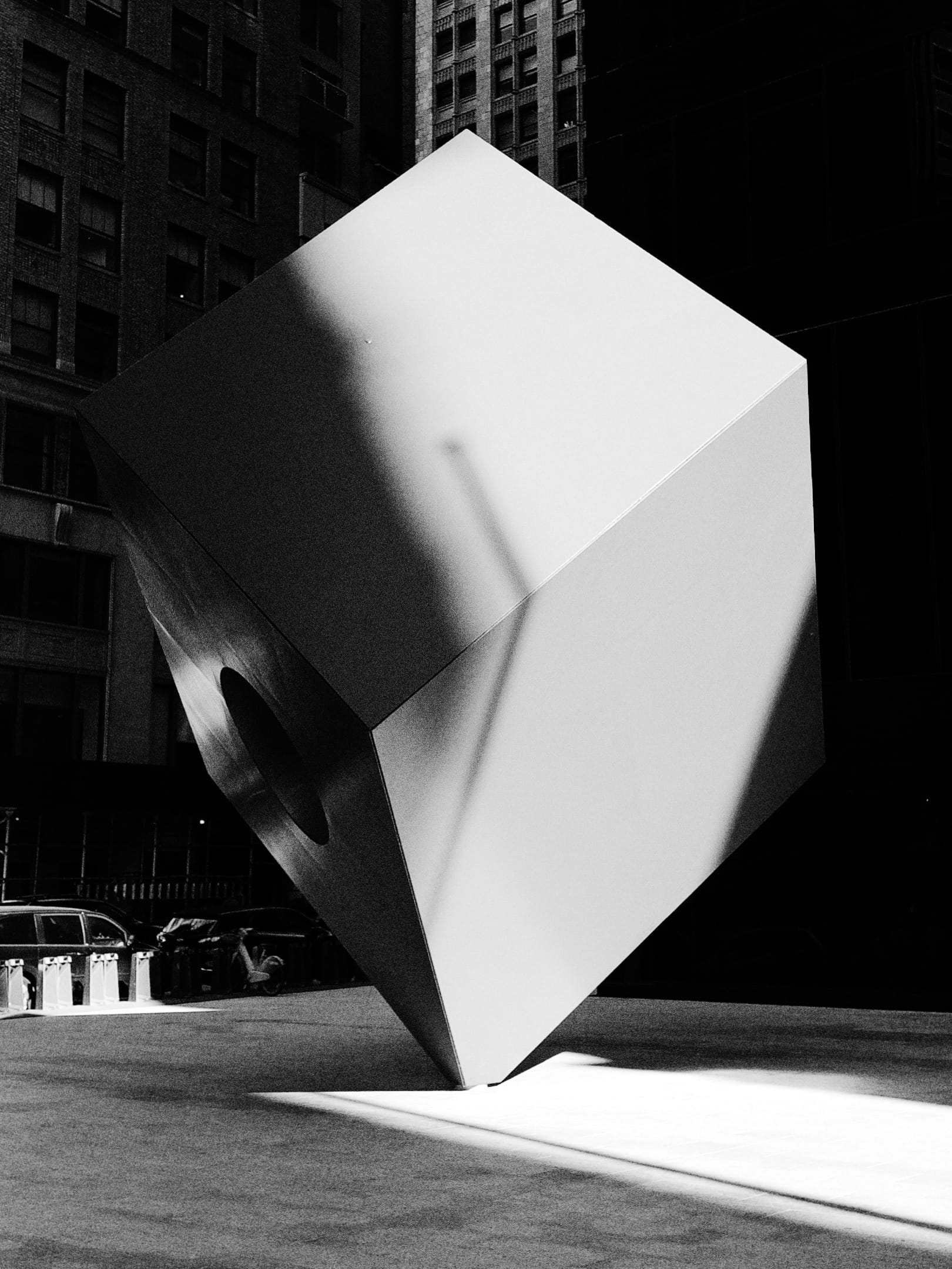

Wall Street, Shot on iPhone

The Verdict

Since it doesn’t have rangefinder, I won’t call it the modern rangefinder. The iPhone Air is the spiritual successor to the Leica M6.

It isn’t a camera for beginners, and you won’t take it on a safari, but the Air’s small size, discreet operation, and unmatched durability make it ideal for street photography, journalism, and candid portraits. You can buy phones with similar specs for half the price, but the premium pays for a beautiful piece of kit that is one-part tool, and one-part fashion accessory.

It’s a camera that distills photography to its essence. It may have less, but that’s what makes it fun. When you tap the capture button, you know that you, not the machine, took the photo.

This article may contain affiliate links.

No AI was used in this article’s production.

All product photos were shot on an iPhone 16 Pro with Halide. All street photography was captured on an M6 or iPhone Air running a pre-release build of Halide Mark III and its built-in grades.